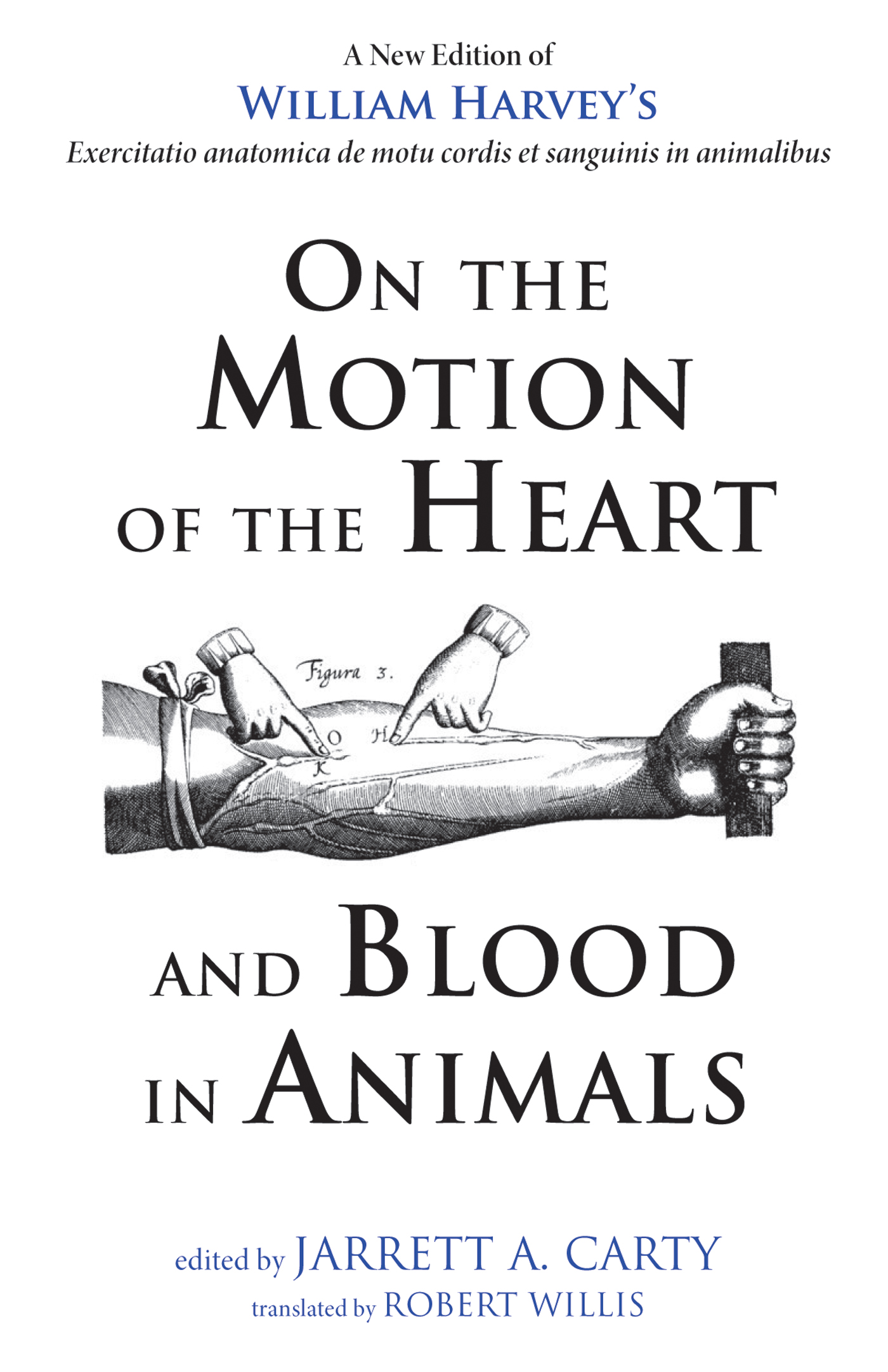

On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals was originally published in Latin. Based on the English translation by Robert Willis, published by the Sydenham Society, London, in 1847 , I have thoroughly rewritten this edition to suit contemporary readership and classroom use. I aimed to be as faithful as possible to Harveys original version; where I felt Williss translation was weak or misleading, I have either replaced it with my own or, in some cases, I have opted to keep Harveys Latin words. In general, I follow the convention in Harveys day of using the Latinized names of Renaissance anatomists (i.e., Johannes Riolanus is used instead of Jean Riolan). I have not italicized Latin medical names that are still in common use today. Lastly, Harvey was inconsistent in his citation of sources, using both marginal notes and in-text references; sometimes he simply failed to cite. Therefore, the footnotes in this text list Harveys references and provide sources he did not name, as well as supplying commentary on difficult text or relevant context.

Acknowledgments

I thank my family for all their enduring love and critical support. I especially thank my lovely wife Nikki for lending her patient ear for all my Harvey related complaints.

As is often the case for new editions and translations, this project became much more time-consuming than originally anticipated; consequently there are many people in my academic world to thank for helping me see this through to publication.

First, I wish to thank Kelly Quinn, an English scholar and neighbor, who provided invaluable help to improve the manuscript. I must take full credit for the errors and shortcomings that remain, but credit for the strengths must partly go to her.

Second, I also wish to thank all my colleagues at the Liberal Arts College whose dedication to undergraduate teachingparticularly outside of their narrow academic specializationsis inspirational. Moreover, I thank them for the confidence they have given me in developing the history of science courses, for which this text is intended.

Third and last, I wish to thank all the students of my history of science classes over the years at the Liberal Arts College. They always confirm my unsurprising claim that Harveys work was a great book of natural philosophy that deserves at least as much attention that we give to it every year. But they have also patiently shown me the need for an updated edition. Therefore, this book is dedicated to them.

An Introduction to the Text

The Life of William Harvey

William Harvey was born on April , , in Folkestone, a port town in Kent in southeastern England. The Harveys were yeomen sheep farmers, but with astute commercial dealings: Williams father Thomas elevated himself to the minor gentry, and several of his sons became successful London merchants. As the firstborn son, William was educated to the best of Thomass means, enrolling at the Kings School in Canterbury in 1588 and staying there for five years. Little is known about Harveys early life, but he must have shown enough academic promise to justify the time and expense of embarking on a university degreethe first of his family to do so. In 1593 , Harvey studied arts at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, and earned his degree in 1597 . He then turned to the study of medicine, which was still in its infancy at Cambridge. After travelling around the continent, Harvey began his doctoral studies at the University of Padua, Europes most prestigious medical school, in . At Padua, Harvey was taught by the famous anatomist Hieronymus Fabricius ( 1537 1619 ). He took his doctorate in 1602 .

Harveys long career began with his return to London, where he would soon rise to prominence in the medical establishment. In , he married Elizabeth Browne, the daughter of a London physician. He was elected a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1607 , and was appointed physician to St. Bartholomews hospital in 1609 , continuing in this post for most of his life. In 1615 , he was made Lumleian lecturer at the Royal College, which required him to give periodic lectures on anatomy using human cadavers and live animals for his demonstrations. It was during these lectures that he developed his new theories on the motion of the heart and blood; his lecture notes formed the basis for On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals (commonly referred to as De motu cordis ) . Harvey was appointed a court physician to King James I in 1618 , retaining this position under Charles I, and in 1639 , he was named senior physician in ordinary. Harvey accompanied Charles I in his Scottish campaigns and during the Civil War, even visiting the king during his captivity at Newcastle in 1646 . Thus Harveys sympathies with the royalist side were public knowledge. Apparently his royalism did not cause severe damage to his standing or reputation during the Commonwealth, however, for after the English Civil War he returned to London and partially resumed his practice. In this period, Harvey published his Anatomical Exercises on the Circulation of the Blood ( 1649 ) and Exercises on the Generation of Animals ( 1651 ). By this time, he was a widower and childless. In the years that followed, he resigned his positions, lived alternatively with his two remaining brothers, and began to suffer from gout and kidney stones. Harvey died of a stroke in 1657 at the age of .

Ancient Anatomy and the Heart

Hippocrates of Kos (c. c. BCE) is generally considered one of the most important ancient medical sources, if not the father of medicine itself. The nearly seventy works attributed to him were in fact, however, a compilation of writings from various authors over two centuries. This Hippocratic School was part of a wider intellectual movement that sought to make health and sickness explicable through natural philosophy. It championed the theory of the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) for explaining wellness and disease, and used this humoral theory to understand human anatomy. Through animal dissection (human dissection being strictly taboo in the classical world), the Hippocratic School knew the basic structure of the heart, but believed that it distributed pneuma (meaning air but also spirit) around the body.