The

Archaeology

of Disease

Dedicated to

Ann Manchester and

Ann Hunter

The

Archaeology

of Disease

Third

Edition

CHARLOTTE ROBERTS AND KEITH MANCHESTER

First published in 1983

Second edition first published in 1995

Third edition first published in 2005

This edition published in 2010

Reprinted 2012

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Charlotte Roberts and Keith Manchester, 1983, 1995, 2005, 2010

The right of Charlotte Roberts and Keith Manchester to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

E PUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9497 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank again the following for their help in the production of this edition of The Archaeology of Disease: Ann Manchester and Stewart Gardner, for their understanding and tolerance; and Durham University, for allowing the first author the time fully to revise the 2nd that forms this paperback edition. Many of the illustrations that are not credited to specific people were produced by Jean Brown (formerly of the University of Bradford, Department of Archaeological Sciences) or the first author; Jeans enthusiasm, understanding and dedication to the photography of human remains are gratefully acknowledged. The authors would also like to thank the late Johs Andersen, Cecil Hackett, William Jopling and Freddie Wells, and Arnold Aspinall and Don Ortner for their guidance and encouragement for previous editions of this book, and Don for his continued help.

The illustrations were further enhanced by many colleagues providing us with permission to use some of their photographs. Particular thanks go to Art Aufderheide (University of Minnesota-Duluth), Pia Bennike (University of Copenhagen) (including on behalf of the Museum of Medical History, Copenhagen), Wilbert Bouts, Patricia Bridges (Queens College, City University of New York), Domingo Campillo (University Autonoma de Barcelona), Peter Davies (Cardiothoracic Centre, Liverpool), Ian Dewhirst, Diane France (France Castings, Colorado), Anne Grauer (Loyola University of Chicago), Diane Hawkey (Arizona State University), Robert Jurmain (San Jose State University), Lynn Kilgore (University of Colorado, Boulder), George Maat (Leiden University), Charles Merbs (Arizona State University), Northumberland Health Authority and the Secretary of State for Health, England, Don Ortner (Smithsonian Institution), the late Juliet Rogers (Rheumatology Unit, Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol), Tony Waldron (Institute of Archaeology, London), and the late Calvin Wells for his tremendous slide collection, curated at the University of Bradford. Other institutions that have allowed the use of illustrations are: Reading Museum, Berkshire, England, the Royal College of Surgeons, London, the Science Museum, Science and Society Picture Library, London, and York Archaeological Trust.

The authors are grateful to a number of archaeological organizations for the provision of skeletal material, curated at the University of Bradford and the Durham University. This material has provided invaluable data and illustrations for this book. Particular thanks are due to Malcolm Watkins (Gloucester City Museum; Gloucester cemeteries), Malcolm Atkin (formerly of Gloucester Archaeology Unit, now Hereford and Worcester Archaeology Unit; Gloucester cemeteries), Northamptonshire Heritage (Raunds, Northampton-shire), Alec Detsicas (Eccles, Kent), John Magilton (Southern Archaeology and Chichester District Council; Chichester cemetery), Gil Burleigh (Letchworth Museum, Baldock; Baldock cemeteries), York Archaeological Trust (Ripon Cathedral) and Rosemary Cramp (Jarrow cemetery).

Finally, the authors would like to thank the numerous people at The History Press who have brought this third edition to fruition. Any mistakes in this book are the responsibility of the authors alone.

The Archaeology of

Disease

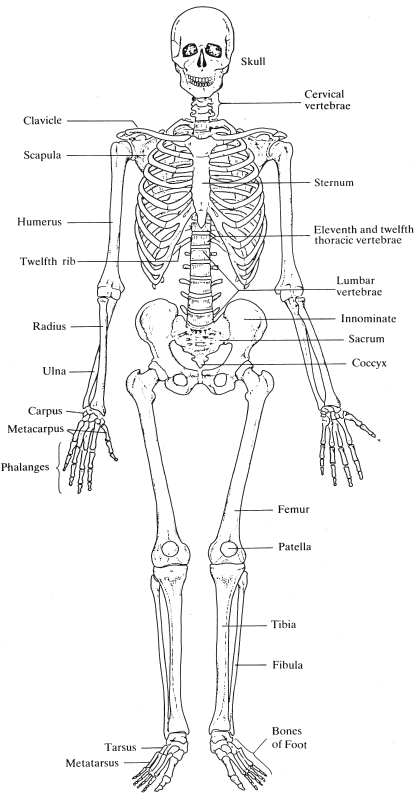

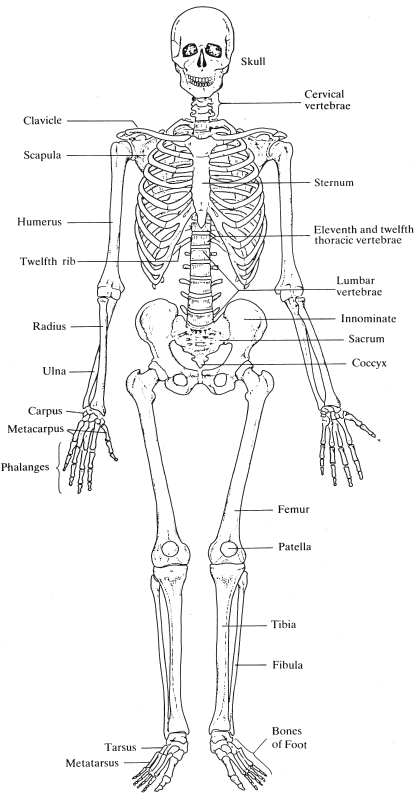

The human skeleton.

CHAPTER 1

The Study of Palaeopathology

Disease is an inevitable part of life, and coping with disease is a universal aspect of the human experience... the experience of disease... is as inescapable as death itself. (Brown et al., 1996: 183)

INTRODUCTION AND DEFINITIONS

The study of palaeopathology examines the origin, evolution and progress of disease through long periods of time and looks at how humans adapted to changes in their environment. Relevant to evolutionary medicine (Nesse and Williams, 1994), it provides primary evidence for the state of health of our ancestors and, combining biological and cultural data (the biocultural or bioarchaeological approach), palaeopathology has become a wide-ranging holistic discipline. Current developments, and the future of palaeopathology, are exciting and are discussed further in the final chapter of this book.

Pathology is the study (logos) of suffering (pathos). In practice, pathology is defined as the scientific study of disease processes. Palaeopathology was defined in 1910 by Sir Marc Armand Ruffer (Aufderheide and Rodrguez-Martn, 1998) as the science of diseases whose existence can be demonstrated on the basis of human and animal remains from ancient times. Palaeopathology can be considered a subdiscipline of biological anthropology and focuses on abnormal variation in human remains from archaeological sites. The study of palaeopathology is multidisciplinary in approach and concentrates on primary and secondary sources of evidence. Primary evidence derives from skeletons or mummified remains. This type of evidence is the only reliable indication that a once-living person suffered from a health problem; whether a specific diagnosis can be made is more of a challenge. However, as Horden (2000: 208) indicates, palaeopathology would seem to provide our... hardest evidence for past afflictions. Secondary forms of evidence include documentary and iconographic (art form) data contemporary with the time period under investigation. Unfortunately, artists and authors in the past have tended to illustrate and describe the more visual and dramatic diseases and ignored those which may have been more commonplace; the mundane, common illnesses and injuries are lost to the palaeopathologist if this type of evidence is considered alone. For example, the mutilating deformities of the infection leprosy, the devastating effects of the Black Death, and the curiosity factor in dwarfism have led to abundant representations of these conditions in art, but coughs, colds, influenza and gastrointestinal upsets, along with cuts, bruises, burns and sprains, would probably have been so common that they would have been irrelevant in the eyes of the writer or artist. In antiquity, those diseases with the greatest impact in terms of mortality, personal disfigurement or social and economic disruption probably evoked the greatest response from society (and its authors and artists). In the past, attitudes towards illness have often been due to the failure in understanding the nature of the disease itself. However, when interpreting disease in the past from secondary sources care must be taken opinions and preferences about what should be described and drawn will affect what is read and seen. Imprecise and incomplete representation may transmit incorrect information. All literary works must be studied carefully within the traditional framework in which their facts are presented (Roberts, 1971). Those aspects of an illness which we consider to be of vital importance in the understanding of a disease may have been considered of no consequence to the observer in the past and may not therefore have been given due prominence in the record. There are also circumstances where a disease description does not correspond with any known disease in the modern world. This may be because it actually does not exist or the disease is just not recognized because of the inaccuracy of its representation. Relevant too is the need to appreciate that different diseases may produce similar signs and symptoms. For example, how does one differentiate between the skin rash of chickenpox, leprosy and measles? It is true to say that specific areas of the body may be affected by the different conditions, and the nature of the lesion may differ, but to be able to determine what disease is being displayed in writing or art necessitates a very detailed representation. Another example is the clinical picture associated with respiratory disease. Cancer, chronic bronchitis and tuberculosis can all result in coughing up blood (haemoptysis) and shortness of breath (dyspnoea), but how would they be distinguished from one another in the written record if only haemoptysis and dyspnoea were being described? However, the diseases which are not displayed in the skeletal record, i.e. those affecting only the soft tissue (e.g. malaria, childhood diseases such as whooping cough and mumps, cholera and typhoid), may be recorded only in art and documentary sources, and therefore, in these cases, this type of evidence is especially invaluable. We do recognize that solely considering skeletal remains for the evidence of disease allows us to deal with only a very small percentage of the disease load in a population. However, as Horden (2000: 208) states: the greater the number and variety of perspectives on the pathological past with which we can engage, the greater the chance that our analysis will not be completely disabled by problems of retrospective diagnosis.

Next page