THE DAO OF THE MILITARY

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

T RANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

| Editorial Board | Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair |

| Paul Anderer | Wei Shang |

| Donald Keene | Haruo Shirane |

| George A. Saliba | Burton Watson |

Th eDAOof theMILITARY

Liu Ans Art of War

Translated, with an Introduction, by Andrew Seth Meyer

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2012 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52688-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bing le xun. English.

The dao of the military : Liu Ans art of war/translated, with an introduction, by Andrew Seth Meyer; foreword by John S. Major.

pages cm. (Translations from the Asian classics)

Translation previously published in: The Huainanzi. New York : Columbia University Press, 2010.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15332-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-15333-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-52688-3 (e-book)

1. Military art and scienceEarly works to 1800. 2. Taoist literature, ChineseEarly works to 1800. I. Liu, An, 179122 B.C. II. Meyer, Andrew Seth, translator, writer of added commentary. III. Title.

U101.B5713 2012

355.02dc23

2011047621

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

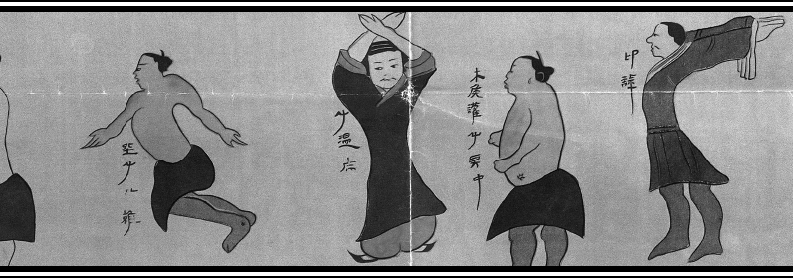

Cover image: Wellcome Library, London.

CONTENTS

by John S. Major

When an ancient Chinese military theorist wrote the classic Military Methods of Master Sun (popularly known in English as The Art of War), he could have had no idea that his book would still be famous nearly twenty-five hundred years in the future, consulted as a guide to strategy not only on the battlefield but also in adversarial situations of all kinds. Master Suns famously cryptic aphorisms, such as When you assemble your army and formulate strategy, you must be inscrutable, have inspired thousands of participants in management seminars around the globe. Many people today who know nothing else about China know of The Art of War. Less widely understood is that The Art of War is not unique; there are a number of ancient Chinese treatises on military matters, and they are by no means all the same. What we have chosen to call The Dao of the Military: Liu Ans Art of War is one such alternative Art of War. It comprises An Overview of the Military, a chapter in the Huainanzi, an important compendium of philosophy and political theory written under the sponsorship of Liu An, king of Huainan, and presented to the imperial throne in 139 B.C.E. As these pages will show, its view of military matters is quite different from that of The Art of War, and different in interesting and important ways.

The publication of the first complete English translation of the Huainanzi in 2010 made that encyclopedic Han-dynasty work accessible to a wide audience for the first time. The product of more than twelve years of toil by a team that included Andrew Meyer and me, along with Sarah Queen and Harold Roth, the Huainanzi translation invites scholarly attention on a text that has hitherto been somewhat neglected by students of early Chinese intellectual history. That statement requires some qualification. Every early China specialist for generations past has known of the Huainanzi. It is described in standard reference works, and many sourcebooks and anthologies of Chinese literature include at least a few passages from the text. A number of translations into English and other Western languages of single chapters or small groups of chapters have been published in recent decades, along with a few interpretive scholarly works. Nevertheless, it has generally been the case that few people have actually read substantial portions of the Huainanzi, certainly not in the original classical Chinese. The Huainanzi has been a text to dip into rather than to read extensively, a text to mine for an apt quotation or a passage parallel to one in some better-known text rather than one to read for its own intrinsic interest. The books ancient bibliographical classification as a miscellaneous work, though originally not pejorative, encouraged a view of the Huainanzi as a mlange of quotations from earlier sources, an unoriginal compendium of relatively minor importance.

The new English translation of the Huainanzi radically challenges that view by taking seriously the claims made for the text by its patron and general editor, Liu An (179?122 B.C.E.). In his poetical postface to the work (chapter 21, the final chapter of the text), Liu An makes two audacious claims for his book: first, that it so effectively synthesizes the best features of all previous books as to render those source texts superfluous, and second, that its reach is so broad and comprehensive as to make unnecessary the writing of any other works in the future. Both claims are obviously wildly overblown, but they nevertheless make clear that the Huainanzi was intended as a comprehensive survey, for a royal audience, of all the essential knowledge of its era. And reading the text from beginning to end makes clear that far from being a miscellaneous grab bag of quotations, the Huainanzi is carefully structured to embody a particular view of the cosmos, humankinds place in it, and the role of human culture and institutions in a well-ordered society. Read from that point of view, it offers a commodious and fascinating window into the intellectual life of early Han China.

As longtime students of the Huainanzi, we hope that the publication of our complete English translation will prove to be a valuable stimulus to the small but growing field of Huainanzi studies, encouraging (especially) younger scholars to explore in depth some of the many potential topics of enquiry opened up by the translation itself. The Dao of the Military is one of the first to take up that challenge. I am delighted that one of the members of the translation team has now taken the further step of analyzing a chapter of the Huainanzi in much greater detail than was possible in the brief chapter introduction in the complete translation. I hope that the next few years will see a surge of studies of particular chapters or themes in the Huainanzi, all of which will enrich our understanding of early Han thought.

The book you are now reading contains the text of Andrew Meyers translation of chapter 15 of the Huainanzi, An Overview of the Military, essentially unchanged (except for the insertion of additional notes) from its appearance in the complete translation volume. What is new here is Meyers extensive analytical introduction to the chapter, which brilliantly demonstrates that (true to Liu Ans vision for the Huainanzi) the chapter is both firmly lodged in the tradition of early Chinese military literature and approaches military matters from its own particular and extremely interesting point of view. Far from being simply a repackaging of earlier military treatises, An Overview of the Military is a strikingly original contribution to the genre. Meyer organizes his analysis under four rubrics that cumulatively provide a comprehensive account of the text and highlight its unique features.

Next page