Russell Bertrand Arthur William - The Conquest of Happiness

Here you can read online Russell Bertrand Arthur William - The Conquest of Happiness full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London;New York, year: 2010, publisher: Taylor and Francis;Routledge, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

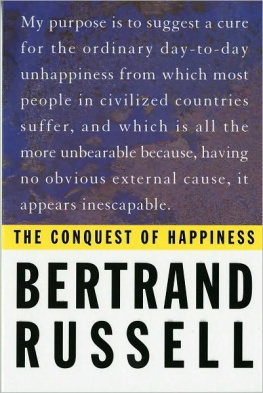

- Book:The Conquest of Happiness

- Author:

- Publisher:Taylor and Francis;Routledge

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- City:London;New York

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Conquest of Happiness: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Conquest of Happiness" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Conquest of Happiness — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Conquest of Happiness" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

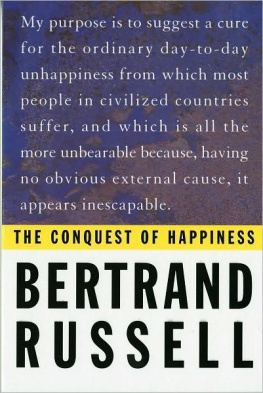

The Conquest of Happiness

Russell asks all the right questions and provides trenchant answers. A deeply human and compassionate book.

Richard Layard

He writes what he calls common sense, but is in fact uncommon wisdom.

The Observer

Commended strongly in these days of false values and confused thinking.

The Listener

As a guide to cheerfulness, Russell could not be bettered.

News Chronicle

Routledge Classics contains the very best of Routledge publishing over the past century or so, books that have, by popular consent, become established as classics in their field. Drawing on a fantastic heritage of innovative writing published by Routledge and its associated imprints, this series makes available in attactive, affordable form some of the most important works of modern times.

For a complete list of titles visit

www.routledge.com/classics

Bertrand

Russell

The Conquest of Happiness

With a new preface by A.C. Grayling

First published in Great Britain by George Allen & Unwin 1930

First published in paperback 1961

First published in paperback by Unwin Paperbacks, an imprint of Unwin Hyman Limited in 1975

First published by Routledge 1993

First published in Routledge Classics 2006 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

The Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation 1996

Preface to the Routledge Classics edition A.C. Grayling 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN10: 0415378478

ISBN13: 9780415378475

C ONTENTS

P REFACE TO THE R OUTLEDGE C LASSICS E DITION

In the early part of his long career, in fact until his mid-forties, Bertrand Russell believed that philosophy was a strictly a technical subject in fact, a branch of logic which had nothing to do with matters of ordinary life. He still held this view during the time that he lived and taught in Peking in the early 1920s, which meant that he lost an opportunity to help the young Chinese intellectuals who asked him for guidance in matters social and political, which they much needed at that tumultuous period of their countrys history. The American Pragmatist philosopher John Dewey was also in China at that time, and did not hesitate to respond to such requests, with the result that he is remembered today in China with some reverence, whereas Russell left scarcely any mark outside Peking University.

But Russells austere technical view of philosophy did not last much longer. His reputation as a philosopher prompted people to ask him for his opinion on every imaginable subject, and when he found it convenient to write non-technical books and articles as a way of making money, he found a readership eager to know what a philosopher could say on the pressing questions of life and morality which, afresh in every generation, interest the more reflective members of the public. Such people could of course go to the writings of the great thinkers of the past, among them the philosophers of classical antiquity, to help them work things out for themselves; and some do. But a special interest always attaches to what philosophers of ones own day think, because they share the very same experience and problems as oneself, which gives their perspective an added value. It was this need that Russell found himself able to meet when at last he turned his attention to it.

The seeds of the change in Russells attitude to popular philosophy had in fact been sown during the First World War. He had campaigned throughout that horrendous event as an antiwar activist, twice falling foul of the law as a result, and having to spend some months in prison. He wrote and lectured much in relation to his campaign, but at that time did not think of the work as an aspect of the philosophical enterprise. The idea that a thinker might be engaged with the pressing questions of the day, trying to bring to bear considerations of principle and the resources of thought from the great moral and political debates of the history of philosophy, for some strange reason seemed alien to British philosophers in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first six decades of the twentieth century, during which academic teachers of philosophy expressly disavowed any interest in or responsibility for them. What makes this surprising is that Russells own (secular) godfather, John Stuart Mill, was anything but a disengaged philosopher, but rather a shining example of one who as with his father John Mill and his fathers mentor Jeremy Bentham tries to do his bit to improve the world.

By the mid and late 1920s, Russell had made the connection between the sort of work he had done when campaigning against the First World War, and the constant invitations he was receiving to address the needs of contemporary society. Moreover he thought that education was the key to preventing wars and benefiting the future, as did many other intellectuals at the time (among them Karl Popper and Ludwig Wittgenstein, who also chose to become teachers), and he therefore decided to open a school. All these factors led to his rejoining the great tradition of philosophers who have been teachers and guides as well as scholars, and the result was the beginning of many years of writing, lecturing and campaigning on a wide range of social and political issues, from education and morals to the threat of nuclear war.

To see how fully Russells change into a public philosopher possessed him, one need only look at the following small sample from his enormous list of writings: On Education, Especially in Early Childhood (1926), published that same year in America as Education and the Good Life and later abridged as Education of Character. In 1927 he published Why I Am Not a Christian, in 1929 Marriage and Morals, and in 1930 The Conquest of Happiness. All this time he was writing articles on these and related themes, among them a weekly 600-word column for the Hearst newspapers in America, in which he dispensed elegantly tailored snippets of observation and wisdom, some of them little gems. Both Why I Am Not a Christian and Marriage and Morals proved enduringly controversial. The latter lost Russell his appointment at the City College of New York in 1940 on the grounds of its immorality, and ten years later won him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

The most distinctive thing about Russells views in these non-technical, social and moral spheres is their resolute common sense, lucidity and open-mindedness. Think of the contrast between, say, a French savant waving his Gauloise about and lucubrating profoundly, in obscure language, about life, sex and ideas, and then look at the clarity, openness and good will of Russells writings on the same subjects. Among too many of the intellectual brotherhood, clarity and openness is scorned as being too simple, even simplistic, the argument being that it perforce ignores all nuance, all subtlety, all profundity. This is a spurious objection. Some of the deepest truths are simple, when seen in the clearest light, and it takes a lucid intellect to grasp them so thoroughly that their simplicity can be brought into that light and offered to all, not just the privileged few. There is a perennial suspicion that Gauloise-waving intellectuals deliberately obfuscate to exclude

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Conquest of Happiness»

Look at similar books to The Conquest of Happiness. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Conquest of Happiness and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.