The Politics of Passion

BETWEEN MEN ~ BETWEEN WOMEN

The Politics of Passion

Womens Sexual Culture

in the Afro-Surinamese Diaspora

Gloria Wekker

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2006 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-50601-4

The publication of this book was made possible by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wekker, Gloria.

The politics of passion : womens sexual culture in the Afro-Surinamese diaspora / Gloria Wekker.

p. cm. (Between menbetween women)

Revision of the authors thesis published in 1994 under title: Ik ben een gouden munt, ik ga door vele handen, maar ik verlies mijn waarde niet.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-13162-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-231-13163-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. WomenSurinameParamariboSexual behavior. 2. WomenSuriname ParamariboIdentity. 3. Sex customsSurinameParamaribo. 4. LesbianismSuriname Paramaribo. 5. CreolesSurinameParamaribo. I. Wekker, Gloria. Ik ben een gouden munt, ik ga door vele handen, maar ik verlies mijn waarde niet. II. Title. III. Series.

HQ29.W476 2006

306.76'5089960883dc22

2005054320

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

BETWEEN MEN ~ BETWEEN WOMEN

Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Studies

Terry Castle and Larry Gross, Editors

Advisory Board of Editors

Claudia Card

John DEmilio

Esther Newton

Anne Peplau

Eugene Rice

Kendall Thomas

Jeffrey Weeks

BETWEEN MEN ~ BETWEEN WOMEN is a forum for current lesbian and gay scholarship in the humanities and social sciences. The series includes both books that rest within specific traditional disciplines and are substantially about gay men, bisexuals, or lesbians and books that are interdisciplinary in ways that reveal new insights into gay, bisexual, or lesbian experience, transform traditional disciplinary methods in consequence of the perspectives that experience provides, or begin to establish lesbian and gay studies as a freestanding inquiry. Established to contribute to an increased understanding of lesbians, bisexuals, and gay men, the series also aims to provide through that understanding a wider comprehension of culture in general.

For three Caribbean women

Esseline Fredison, 19221982

Juliette Cummings, 19071998

Audre Lorde, 19341992

Contents

Mi gome kon

sootwatra bradi

tak wan mofo,

ala mi mati,

tak wan mofo.

mgo me kon...

[I went awayI am coming back

the ocean is wide

conjure up the ancestors

all my friends,

conjure up the ancestors

I went away

I am coming back... ]

TREFOSSA, 1957

This book is one incarnation of an interest that first presented itself to me about twenty-five years ago. While working on my masters thesis in cultural anthropology at the University of Amsterdam (1981), I came across the book Suriname Folk-lore (1936) by Melville and Frances Herskovits. It was a treasure trove to me, child of a first generation of postWWII middle-class Surinamese migrants to the Netherlands whose main ambitions were for their children to forget the past and step unquestioningly into the Dutch promised land. My parents ambitions for us included becoming model Dutch citizens, which meant first and foremost studying hard. Being versatile in Creole culture or the Surinamese creole they sometimes spoke with each other, Sranan Tongo, was not high on their lists of priorities. Sitting in the library of the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam, I relished the Herskovitses lively accounts of Creole working-class womens culture. I was intrigued by their accounts of the mati life and the institutions supporting it like the birthday party and lobi singi. The Herskovitses opened up a new world to me and at the same time, like a lightning bolt, made me see connections with phenomena I perceived around me in Amsterdam, where a new, more heterogeneous group, in terms of ethnicity and class, of Surinamese migrants had settled after independence (1975). Too late to change my M.A. thesis, whose focus was matrifocality, I made myself a promise to return to that world of working-class Surinamese women at a later date. The dream I dared to entertain was to make a contribution to the contemporary ethnography of Afro-Surinamese womens lives.

This dream has since blossomed and transformed into the book you now hold in your hands. It first took root in the work in sociocultural anthropology that I pursued as part of my doctoral research at UCLA. It has involved living, working with, and interviewing twenty-five working-class women. In the past decade and a half I have made more than six trips to Suriname, keeping in contact with many of these women. My initial dream has transformed into a longitudinal, transcontinental study, realized in the pages of this book. Its manifestation is threaded with webs of friendships and indebtedness that span three continents, North America, South America, and Europe, where I am located.

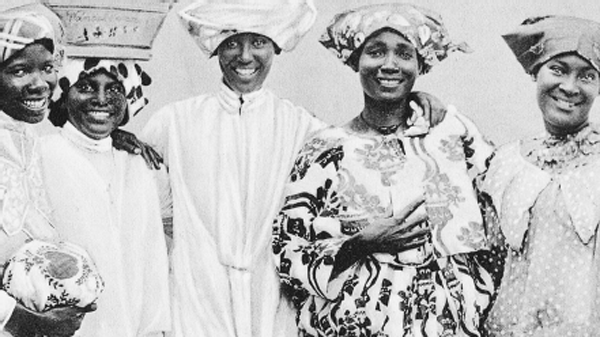

In March 1990, having just arrived in Paramaribo, I went to a traditional Afro-Surinamese afternoon birthday party, given in honor of the sixtieth birthday of a prominent male union leader. I went with an older woman whom Id met through the YWCA where I had started to volunteer. The majority of guests were older Creole as a tribute to the women who were to become central to my studies and to my life in the years that followed.

Creole Women

Like stately ships they are

bobbing and streamered

fully adorned

whispering chintz skirts

lined gold braided

digressing

from board to water line

anyisa, anyisa

motyo tie

let them talk

sailors tie

like stately ships they are

swaying cleaving climbing

to the beat of their own drummer

A redskirted robust flagship

leads the squadron

enlarging

grace of gracefulness

she glides to the side

cigar in hand

prepares the others

on their way to the harbor

a triumphal arch, a beacon

chivalrous and eager

like a young naval officer

and always always

dancing flowing floating

to the beat of her own drummer.

First and foremost, I want to thank Misi Juliette Cummings and the many other women in Suriname who opened their hearts so that I could understand their lives. In the same way in which the armadillo hides underneath its carapace, these women will remain pseudonymous here, carrying their mostly self-chosen names. Without them, I could not have written the texts that I have authored in the past decade and a half. More than that, their influence on my life has been immeasurable. I can never hope to repay this debt, but I trust I have succeeded in accomplishing what several women have explicitly asked me to do: mek mi tyar den tori go moro fara/may I carry their stories further.