First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD POLITICS

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

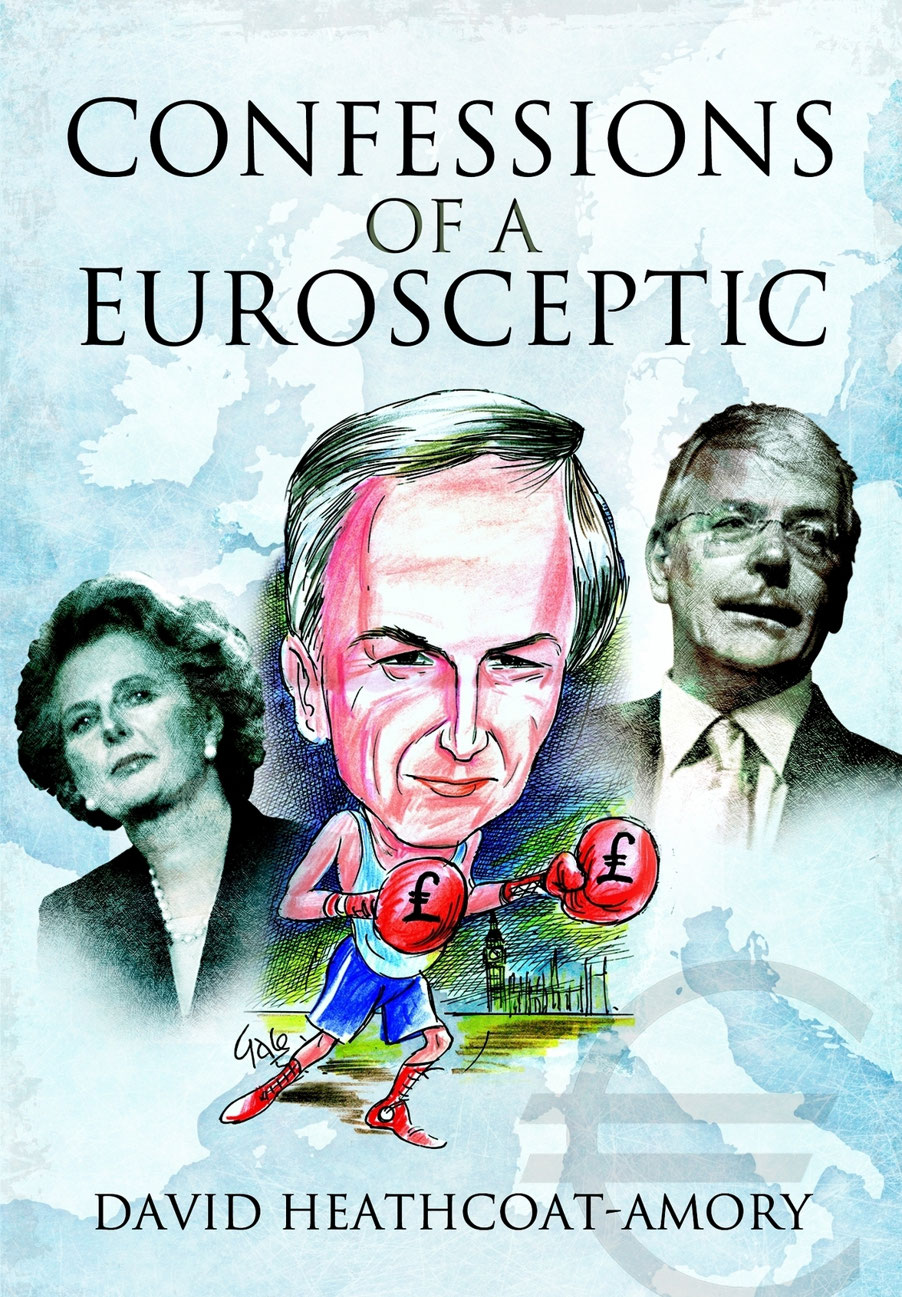

Copyright David Heathcoat-Amory, 2012

9781783036189

The right of David Heathcoat-Amory to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission

from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Table of Contents

Is not every meanest day the conflux of two eternities.

Thomas Carlyle

Foreword

During the twenty-seven years I was a Member of Parliament, our relationship with the European Union was the source of many hopes, fears and failures. It caused constant discord and strife, and contributed to the downfall of two prime ministers. The European question was central to my own career as a backbencher, then as a minister until I resigned, and then again in opposition. It remains an unresolved issue today and has created a new economic crisis.

The story that follows charts my own journey from acceptance of the EU to rejection of it, and my involvement in these controversies as Minister for Europe and as Paymaster General. It is not a history of the subject, but a personal account which illustrates how and why crucial decisions and mistakes were made. We need to understand these mistakes if we are not to repeat them. I shall give proposals for what needs to be done now to create a democratic Europe based on the principles of self-government and international cooperation, or, failing that, a different relationship between Britain and the EU.

It is sometimes alleged that hostility to the EU is driven by blinkered nationalism or xenophobia, but in my case it was the early experiences I had abroad that convinced me of Britains global responsibilities, and it was often the EU which I found to be narrow and inward looking. I therefore start with a brief section on my early life and travels, which provided a context for my political beliefs.

Throughout all the ups and downs of political life I have been sustained by Linda, and together we faced the loss of our son. I dedicate this memoir to her.

Chapter 1

Before Europe

I come from a family of West Country textile manufacturers, descended from John Heathcoat, the son of a farmer who in 1808 invented a machine for making lace. He became an MP for Tiverton, sharing the seat with Lord Palmerston, and started the family political tradition.

My father, being the youngest of four brothers, joined the army, so my childhood was one of frequent moves: to Germany, then Egypt, then a succession of postings in England, ending up in Yorkshire. Family life centred on Devon, where my uncle Derry was MP for Tiverton and was Chancellor of the Exchequer under Harold Macmillan. From an early age I absorbed a belief in free trade, internationalism, and the imperative that Britain should maintain her competitiveness in industry and commerce.

After leaving Eton, aged 17, I went for a year to Canada, where I worked for the Hudsons Bay Company, first in Montreal and then at a trading station on the Moose River in Northern Ontario. After this I went on a lengthy trip across Canada and the United States in an anti-clockwise arc, travelling by Greyhound bus on a $99 for 99 days ticket. I had some addresses and contacts but mostly travelled alone with no bookings, relying on finding a cheap hotel on arrival. I have never forgotten the generosity of a black truck-driver in Flagstaff, Arizona, who put me up in his own home when he spotted me late at night, obviously in need of somewhere to stay. I was captivated by the whole North American experience: the energy, the freedom, and the prosperity which seemed to be spread much more widely than at home. Eventually I reached New York and crossed back to England by ship in time to go up to Christ Church, Oxford, in 1967 to start my degree.

I engaged sporadically in the Oxford Union, and became president of the Oxford University Conservative Association, a large and competitive organization known for its imaginative electoral practices. The late 1960s were a time of political turmoil, with giant demonstrations in Grosvenor Square against the Vietnam War, student sit-ins and left-wing factionalism, as disillusionment with the Labour government set in. There was increasing alarm about Britains economic performance, as successive industries were ravaged by foreign competition and our industrial relations became ever worse. My only sporting achievement during those three years was to box for the university.

After leaving Oxford in 1970, I resolved to see as much of the world as possible before starting in business, so set off to explore South America, then in stages crossed the Pacific to New Zealand, arriving in Australia in time for Christmas. In the New Year I moved on to Singapore, where the Commonwealth Heads of Government Conference was starting, and I managed to get accredited as a reporter for the event. In a world less traumatized by terrorism access was easier then. The Conference issued the Singapore Declaration of Principles which re-established the Commonwealth as a voluntary association of independent sovereign states, which would cooperate in the pursuit of peace, self-determination, free trade, equal rights and the elimination of poverty. This seemed to me to be an admirable definition of international cooperation but Ted Heath, who led for the British government, was already negotiating to join the European Economic Community, with a different destination in mind.

Using the same credentials as a newspaper correspondent I next went to South Vietnam, where the Americans still had 300,000 troops. They had already lost 50,000 dead, and the political situation was serious, as the South Vietnamese government lacked the political strength to be a reliable foundation for the American military effort. I visited a number of combat bases around Hue and Da Nang, and witnessed an extraordinary act of bravery by an American GI who threw himself on a grenade which had been lobbed over the perimeter fence and had landed amongst us. By chance the Chinese fuse failed to detonate and he was not killed, but I wrote a testimonial recording the incident, and R.B. Helle of the 5th Marines was subsequently awarded a Navy Cross for his action.

Next page