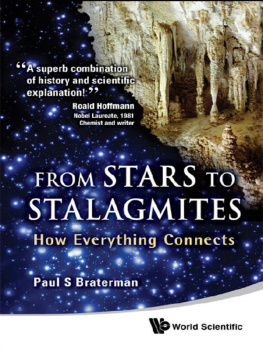

FROM STARS TO

STALAGMITES

How Everything Connects

FROM STARS TO

STALAGMITES

How Everything Connects

Paul S Braterman

University of Glasgow, UK

Publishedby

World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

5 Toh Tuck Link, Singapore 596224

USA office: 27 Warren Street, Suite 401-402, Hackensack, NJ 07601

UK office: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

FROM STARS TO STALAGMITES

How Everything Connects

Copyright 2012 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the Publisher.

For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. In this case permission to photocopy is not required from the publisher.

ISBN-13 978-981-4324-97-7 (pbk)

ISBN-10 981-4324-97-3 (pbk)

Typeset by Stallion Press

Email:

Printed in Singapore.

Contents

1. The Age of the Earth An Age-Old Question

Who thought what and when, and why

2. Atoms Old and New

From Democritus to Rutherford

3. The Banker Who Lost His Head

Lavoisier, gunpowder, revolution, and the birth of modern chemistry

5. The Discovery of the Noble Gases Whats so New About Neon?

A tiny difference in density leads to a whole new group of elements

9. Making Metal

Iron from the sky. Philistines and Phoenicians.

Domestic uses of arsenic. Eros in Piccadilly. The jet age

10. In Praise of Uncertainty

Unavoidable, and a good thing too

11. Everything is Fuzzy

And the smaller, the fuzzier. Waves are particles.

Particles are waves. Crisis in the atom.

12. Why Things Have Shapes

Lewiss magic cubes. Stealing, sharing, double counting. The power of repulsion

13. Why Grass is Green or Why Our Blood is Red

An old question answered. From sunlight to sugar.

A brief history of colour vision. Blood and iron.

14. Why Water is Weird

Fragile bonds. Floating ice and foreign policy.

Molecular recognition and the molecules of life

15. The Sun, The Earth, The Greenhouse

Yellow-hot sun, infrared-warm Earth. When it comes to carbon dioxide, more is more. Disinformation and denialism

16. In The Beginning

From Big Bang to small planet. The birth and death of stars. Size matters. The making of the elements. Vital dust

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank the many people who have helped make this book possible: my darling wife Rebecca, without whom none of this would have been accomplished; my students and colleagues over many years, and in particular my students from TAMS, the Texas Academy of Mathematics and Science in the University of North Texas, for whom much of this material was originally written; Roald Hoffmann, Peter Atkins, and Steve Newton for early encouragement; my colleagues at CESAME, the [New Mexico] Coalition for Excellence in Science and Mathematics Education, and BCSE, the British Centre for Science Education; numerous individuals for helpful comments, reading parts of the text, or supplying materials, including Ariel Anbar, Mark Boslough, Laura Braterman, Professor D. Chakrabarti, John Crooks, Tais Dahl, Alwyn Davies, John Fleck, Haim Harari, M. Kim Johnson, Jim Kasting, Bernard Knapp, Nick Lane, Jim Marshall, Diana Mason, Steve Mojzsis, Ian Orland, Philipp Podsiadlowski, Thilo Rehren, Gary Rendsburg, Bryan Reuben, Merav Segal, Fritz Stern, John Wiltshire, and Jaime Wisniak; the ever-helpful and well-informed library staff at UNT and Glasgow; and V.K. Sanjeed and the editorial team at World Scientific for transforming my raw manuscript into the volume you are now reading.

Introduction

If we assume weve arrived, we stop searching, and we stop developing.

Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell,

discoverer of the first known pulsar

Science is a journey. What we know cannot be divorced from how we came to know it. We make progress, we overcome obstacles, we pursue blind alleys, take lengthy detours, make breakthroughs, and are rewarded with fresh vistas.

When discussing the tangled paths that have led to our present vantage point, I have tried to strike a balance between the wisdom of hindsight, and discussing complex issues as they appeared to their discoverers. I have presented topics in an order chosen for ease of understanding, which is rarely the same as the order in which the discoveries were made. At the same time, I have tried not to pick heroes and villains, or even winners and losers, on the basis of what we know today. Science is disputatious, errors can be fruitful, and the opponents of a new concept help refine it through their very criticisms.

This book is unique in its range of subject matter, its level of treatment, and the manner in which the material is related to its historical and intellectual context. The topics chosen are of fundamental importance, of topical interest, or illustrate particularly important interactions between scientific developments and society. Each topic is presented within its historical context, and with descriptions of the leading figures and what was at stake for them. Finally, the underlying science is discussed in nontechnical language in a context that makes it meaningful, and this principle is applied to such difficult topics as thermodynamics and the nature of chemical bonding.

The book is all about how things connect, in three rather different senses. Richard Feynman once selected, as the single most important statement in science, that everything is made of atoms. It follows that the properties of everything depend on how those atoms are connected to each other. At the same time, our knowledge of this topic, as of every other, is the hard-won product of human endeavour. Science is not a mass of dead data, but a vibrant cultural activity. There are reasons why science has flourished in some periods but not others, why scientists chose to work on the particular problems that they did, and why one solution, and not necessarily the best solution, seemed to them to be preferable to another. There are also obvious connections between scientific discoveries and historical outcomes, although these outcomes may be very different from what the discoverers had in mind. So that is the second kind of connection, the connection between science and society. The third kind of connection is within science itself. Ideas generated in one context prove fertile in another, and reality does not respect the arbitrary divisions we make between different subjects.

The chapters cover a range of topics that seem to me particularly important or engaging. The book starts with the age of the earth, and concludes with the life cycle of stars. In between, we have atoms (and molecules) old and new, the discovery of the noble gases, synthetic fertilisers and explosives, the ozone hole mystery and how it was solved, reading the climate record, the extraction of metals, and how the greenhouse effect on climate really works. The different ways in which atoms and molecules interact with each other are described in context as they arise. A chapter in praise of uncertainty leads on to the fuzziness and sharing of electrons, and from there to molecular shape, grass-green and blood-red, the wetness of water, and molecular recognition as the basis of life.