Contents

Guide

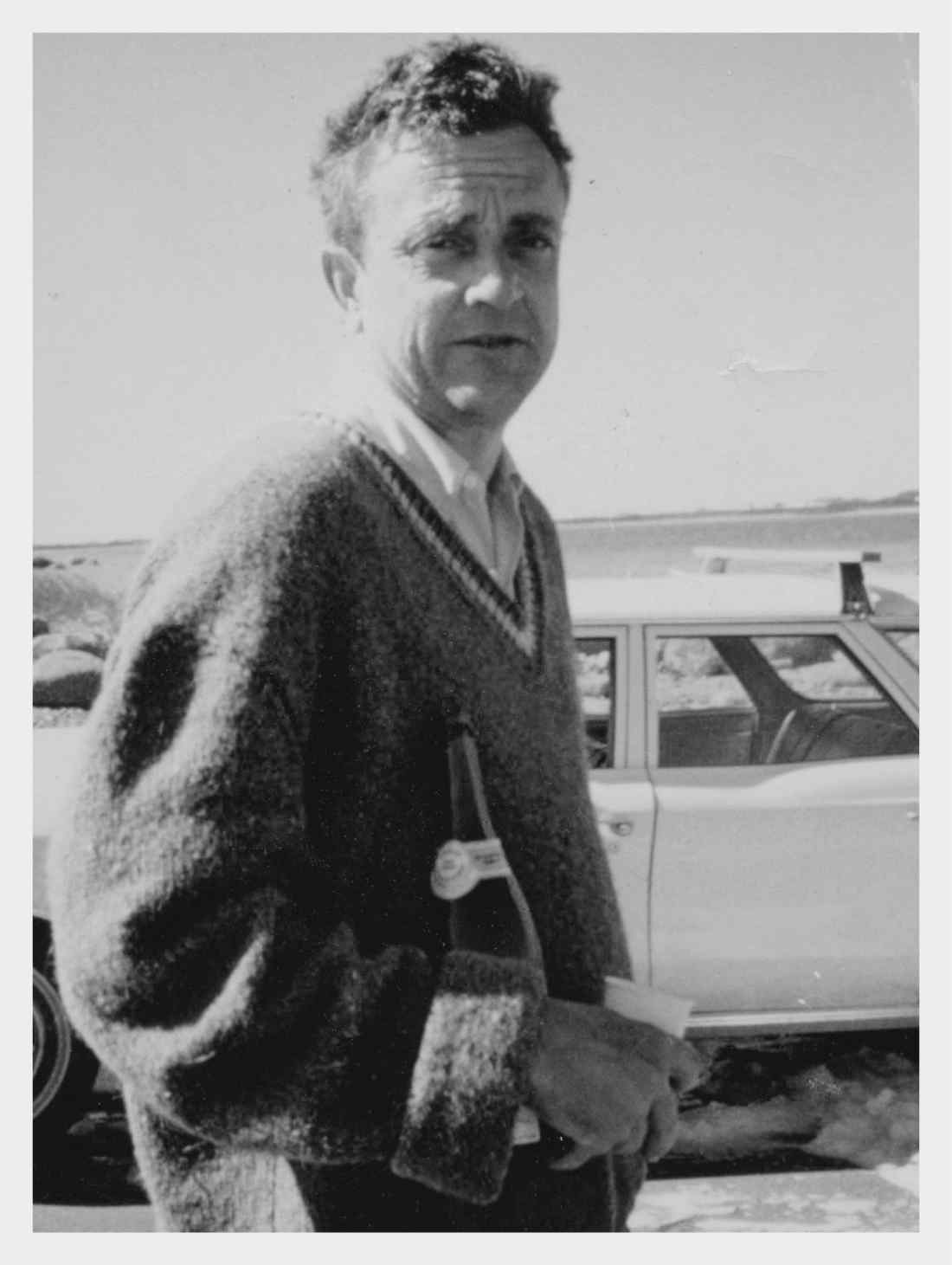

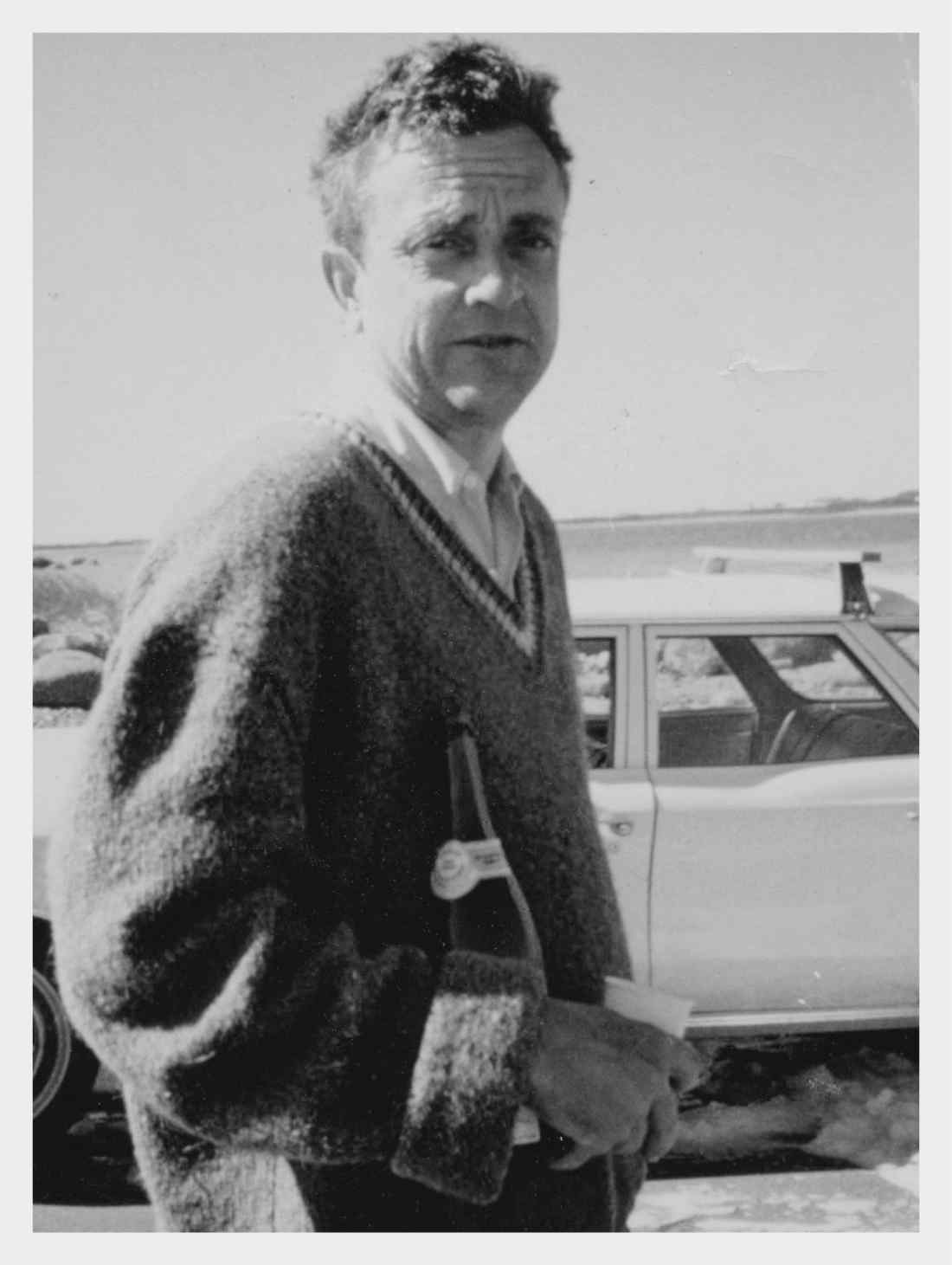

Kurt Vonnegut, Barnstable Bay, Massachusetts, 1969 . Photo: Suzanne McConnell.

Pity the Reader

Copyright 2019 by Trust u/w of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.

Previous publication acknowledgment, see

Electronic edition published 2019 by RosettaBooks

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

ISBN (epub): 978-0-7953-5283-6

Book design by Stewart Cauley

www.RosettaBooks.com

FOR ALL MY STUDENTS, PAST AND FUTURE, AND FOR ALL OF KURTS.

Write like a human being. Write like a writer.

kurt vonnegut jr. to his students at Iowa Writers Workshop, 1966

Introduction

Here we go again with real life and opinions made to look like one big, preposterous animal not unlike an invention by Dr. Seuss, the great writer and illustrator of childrens books, like an oobleck or a grinch or a lorax, or like a sneech perhaps.

kurt vonnegut , Fates Worse than Death

I was a student of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.s at the University of Iowa Writers Workshop in the late s, and we remained friends from those years until his death. I gained a great deal of wisdom from him as a writer, as a teacher, and as a human being. This book is intended to be the story of Vonneguts advice for all writers, teachers, readers, and everyone else.

Vonnegut was not famous when he started teaching at the Iowa Writers Workshop. Hed published four novels. He was working on Slaughterhouse-Five . He was forty-two years old.

The first time I saw him (and I didnt know who he was), he struck my funny bone. He stood in front of a lecture hall with the other writers who were to be our teachers. He was tall, with curving shoulders (a man shaped like a banana, as he once described himself), and he was smoking a cigarette in a long black cigarette holder, tilting his head and exhaling smoke, with a clear awareness of the absurdity and affectedness of it: in other words, he hadas Oscar Wilde said is the first duty in lifeassumed a pose.

He was, I learned later, seriously trying to reduce the effects of smoking by using the cigarette holder.

The Iowa MFA was a two-year program, long enough so that students eventually gravitated, as if by osmosis, to teachers with whom they had an affinity. I found my way to Vonneguts workshop classes by my second year.

Meanwhile I read Cats Cradle and Mother Night , the two books hed most recently published. So I became acquainted with him as a writer through those novels at the same time as I was getting to know him as a teacher and a person.

I lived next door to the Vonnegut family my first year, in a place inhabited by grad students called Blacks Gaslight Village. Our geography continued to be adjacent. I visited Kurt in Barnstable, saw him in Michigan when I first taught and he lectured there, moved to New York City about the same time he did, and for the last thirty-five years have spent summers an hour from where he lived for two decades on Cape Cod. Kurt and I had lunch occasionally, wrote letters, spoke on the phone, ran into each other at events. He sent a lovely blown-glass vase as a wedding present. We never lost touch.

You probably met Vonnegut also through reading his books, assigned in high school or college or read independently, depending on your age. If you read Slaughterhouse-Five , the most well known, you also know the experience that drove him to write that book because he introduces it in the opening chapter: as a twenty-year-old American of German ancestry in World War II, he was captured by the Germans and taken to Dresden, which was then firebombed by the British and Americans. He and his fellow prisoners, taken to an underground slaughterhouse, survived. Not many other people, animals, or vegetation did.

That event, and others, fueled his writing and shaped his views. (It did not, however, as is often assumed, initiate it. He was already headed in the direction of being a writer when he enlisted.) I intend to guide you through the maze of his advice like a director-puppeteer, relating experiences from his life when they shed light on how he obtained the wisdom he imparts; specifying, insofar as possible, from what point in his life a piece of advice derivedas a beginner, mid-career, or a mature writer; and telling anecdotes about him and from my own life, when relevant.

I was asked to write this book at the behest of the Vonnegut Trust. Dan Wakefield was supposed to do it. But exhausted from compiling two other marvelous books of Vonnegut work, Letters , an annotated selection of letters, and If This Isnt Nice, What Is? , an anthology of speeches, and yearning to return to his own fiction, he phoned me. Youre the perfect person to do this book, he said, persuasively. Youve been a teacher of writing, youre a fiction writer yourself, you were his student, and you knew him. Its a great fit.

About percent of it had to be the words of Kurt Vonnegut. Otherwise, how it was composed would be entirely up to me.

All I had to do, Dan said, was write an introductory proposal, and send it and the profiles I had published on Vonnegut in the Brooklyn Rail and Writers Digest , as evidence of my capability and writing style, to the head of the Vonnegut Trust, Vonneguts friend and lawyer Don Farber, and the e-book publisher Arthur Klebanoff, head of RosettaBooks. Dan Wakefield had already told them about me.

A month later, while volunteering at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library table at the Brooklyn Book Fair, the librarys director, Julia Whitehead, introduced me to Dan Simon, the founder of Seven Stories Press, who had published the final two books by Vonnegut, and knew him well. I explained this project. Simon murmured, Id love to publish that book. The result was a new contract between the Vonnegut Trust, RosettaBooks, Seven Stories Press, and myself. Voil. Whatever form youre reading this in, weve got you covered.

Wilfred Sheed said of Vonnegut, He wont be trussed up by an ism, even a good one. He preferred to play his politics, and even his pacifism, by ear. Vonnegut was prone to seeing the other side of the coin, ambiguity, and contradiction.

He had, after all, been captured, imprisoned, and forced into labor carting corpses by an enemy regime rotten with idolatry, decayed by a peoples desire for easy, authoritarian solutions.

He would appreciate this palindrome by Swiss artist Andr Thomkins: dogma i am god .

For my part, I want to avert, as much as possible, my own and the readers impulse to make dogma out of Kurt Vonneguts advice. One way I hope to accomplish that is by adopting the concept of endarkenment.

Its borrowed from Profound Simplicity by Will Schutz, published in 1979 , the one book that gives meaning to the Human Potential Movement, according to the cover. Schutz, a leading psychiatrist in that movement, lists his credentials early on: hed explored every mind-, body-, and soul-expanding avenue the movement had yielded up. Hed also led innumerable seminars at Esalon Institute. Its a concise, down-to-earth, truly helpful book (presently out of print). But the part that has stuck with me for forty years is his final chapter, Endarkenment. It begins, Sometimes my striving toward growth becomes the object of amusement to the part of me that is watching me. He tired, occasionally, of that striving and rebelled.