Table of Contents

Guide

Pages

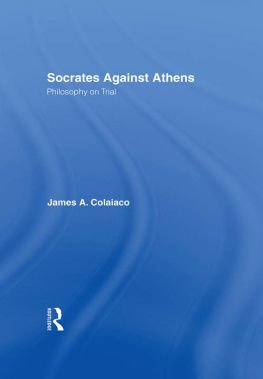

Classic Thinkers

Richard T. W. Arthur, Leibniz

Terrell Carver, Marx

Daniel E. Flage, Berkeley

J. M. Fritzman, Hegel

Bernard Gert, Hobbes

Thomas Kemple, Simmel

Ralph McInerny, Aquinas

Dale E. Miller, J. S. Mill

Joanne Paul, Thomas More

A. J. Pyle, Locke

James T. Schleifer, Tocqueville

Cline Spector, Rousseau

Andrew Ward, Kant

Socrates

William J. Prior

polity

Copyright William J. Prior 2019

The right of William J. Prior to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2019 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2973-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-2974-2(pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Prior, William J., author.

Title: Socrates / William J. Prior.

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA : Polity Press, 2019. | Series: Classical thinkers | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009943 (print) | LCCN 2019015932 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509529766 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509529735 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509529742 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Socrates. | Philosophy, Ancient.

Classification: LCC B317 (ebook) | LCC B317 .P75 2019 (print) | DDC 183/.2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019009943

Typeset in 10.5 on 12pt Palatino

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

For my grandchildren

Preface

This is a book intended for beginners in the study of Socrates. It is not a book for scholars. It contains views, some of them controversial, on some issues of concern to scholars, but it generally avoids debate on those views. Nothing in this book presupposes familiarity with the scholarly literature on Socrates. The book does presuppose some familiarity with Plato's works, including the Apology, Crito, Republic, and some other dialogues. It should be read in conjunction with those. The first chapter should be read in connection with Plato's Apology, the fourth in connection with the Euthyphro, the seventh in connection with the Crito, and so on with the other chapters. There are many good translations of Plato's works available today. The book draws quotations from the Hackett edition of Plato's complete works, because it is the version most familiar to today's readers, but it refers to the passages in the way that is standard among scholars, using the Stephanus pagination in the margins of the pages of most translations. The reader can check the Hackett translations against any others that are available.

Most of this book concerns the character Socrates, as he is depicted in a certain set of Platonic works, which I refer to as the elenctic dialogues. The first chapter is concerned with the life of the person who stands behind that character, and attempts to place that life in the context of the major events of its time. Because Socrates left no written record of his philosophical views it is impossible to state definitively what the relation is between the historical Socrates and the character in Plato's works. This is the Socratic problem and it has no solution. Even when we read about the trial of Socrates, a public event witnessed by approximately five hundred jurors as well as by other Athenians, we rely on accounts of Plato and another associate of Socrates, Xenophon, for our understanding of that event.

Beginning with the second chapter, the book offers an account of the nature of the philosophy presented as Socratic in a set of dialogues in which Socrates practices a distinctive method of inquiry, the elenchus. The elenchus is a negative method, aimed at the refutation of the people Socrates has conversations with, his interlocutors, most of whom claim to have expert knowledge on a moral subject, usually the definition of a moral term. In certain dialogues, such as the Crito, this method is put to a positive use; in the Meno this positive use is justified by the introduction of a theory concerning the acquisition of knowledge, the doctrine of recollection. The doctrine of recollection changes our understanding of the elenchus.

Socrates typically professed ignorance concerning the answers to the questions he raised for others. He presented himself, not as a moral expert, but as an inquirer. In the Theaetetus he describes himself as barren. He says that he does not express his view concerning the issues he raises because he is aware that he lacks wisdom. At the same time, however, he suggests possible answers to those questions. He is, in terms of the contrast drawn in the Theaetetus, fertile. Yet he cannot be both. One way of reconciling these two portraits is through the claim that Socrates profession of ignorance is ironic, a claim made by Thrasymachus in the Republic and Alcibiades in the Symposium. Most interpreters do not accept this ironical interpretation; it is not clear, however, that the tension between the two portraits can be resolved in any other way.

.

is devoted to a question generated by Socrates conception of the just life, namely the relation between Socrates and the state. This was a question that arose after Socrates trial: it has been claimed that Socrates was tried as an enemy of the democratic government of Athens. This chapter considers an argument put forward in the Crito by the laws of Athens in favor of civic obedience. Plato presents Socrates as a loyal citizen of Athens; he was also, however, a critic of democracy. Socrates wanted the Athenians to care about virtue rather than wealth or power. He thought that it was moral knowledge that qualified one to rule in the state, and he retains this view in the Republic. The eighth chapter discusses the relation between the Socrates of the elenctic dialogues and the Socrates of the middle dialogues, who is generally thought to be a spokesman for Plato's own views. The chapter compares the two sets of dialogues with respect to several issues: method, metaphysics (including the theory of Forms and the conception of the good), epistemology, psychology, moral theory, and political theory. I argue that the views of the middle dialogues in general grow out of the views expressed in the elenctic dialogues in a gradual manner.