James A. Colaiaco - Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial

Here you can read online James A. Colaiaco - Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Routledge, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial

- Author:

- Publisher:Routledge

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

against

ATHENS

Also by James A. Colaiaco

Martin Luther King, Jr.: Apostle of Militant Nonviolence

James Fitzjames Stephen and the Crisis of Victorian Thought

SOCRATES

against

ATHENS

Philosophy

on trial

JAMES A. COLAIACO

Routledge

New York and London

Published in 2001 by

Routledge

270 Madison Ave,

New York NY 10016

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group.

Transferred to Digital Printing 2010

Copyright 2001 by Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN: 0-4159-2653-X (hb)

ISBN: 0-4159-2654-8 (pb)

Publisher's Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality ofthis reprint

but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent.

To Nancy, my kindred spirit

A NYONE WHO STUDIES the trial of Socrates is indebted to the many scholars who have contributed to our knowledge of ancient Greek philosophy and culture. We are engaged in a collective effort to understand one of the greatest eras of human history. I wish to thank my colleague, Ron Rainey, who read an early draft of my work and offered valuable advice and encouragement. I am also grateful to Paul Eckstein, John Ross, Michael Shenefelt, and Phil Washburn for their readings and suggestions. I wish to thank Dean Steve Curry and the General Studies Program of New York University for providing me with a semester to begin work on this book. The resources of the Bobst Library of New York University, especially the Interlibrary Loan staff, were of immense assistance. I thank my family, including my father, Alfred Colaiaco, and Josephine Ruggeri and Maria Ruggeri, for their abiding support. The memory of my mother, Helen Colaiaco, continues to sustain me. I am grateful to Gayatri Patnaik, formerly an editor at Routledge, for perceiving the value of my project. My greatest debt is to my wife, Nancy Ruggeri Colaiaco, who read each draft of the book, offering many suggestions for its improvement. During the past few years, we have engaged in a dialogue about Socrates and ancient Athens. I am deeply grateful for her insight, encouragement, and love. Such a partner, in mind as well as spirit, is a true blessing. Needless to say, while my book has benefited from the readings and assistance of others, I alone bear responsibility for its contents.

James A. Colaiaco

Baldwin, New York

Ever since Socrates' trial, that is, ever since the polis tried the philosopher, there has been a conflict between politics and philosophy that I'm attempting to understand.

Hannah Arendt

I N 399 B.C., THE GREAT PHILOSOPHER SOCRATES was tried in his native city of Athens and condemned by a majority of citizenjurors. He was sentenced to death for allegedly disbelieving in the gods of the state, introducing new gods, and corrupting the young. Having engaged in a mission to reform the Athenians, fostering the pursuit of virtue and the improvement of the soul, Socrates threatened values and beliefs regarded as essential to the unity and stability of the citycalled the polis by the ancient Greeks. If individuals are free to follow the dictates of conscience in conflict with accepted social norms and laws, order might dissolve into anarchy. Occurring in the wake of the Peloponnesian War, in which Athens suffered a crushing defeat by Sparta, the trial of Socrates summoned many Athenians to reexamine values regarded as fundamental to the city. Socrates' philosophic mission challenged his fellow citizens to tolerate a critical mind who, ironically, could only have been produced in democratic Athens.

In the Apology, Plato has transmitted to us a re-creation of the trial of Socrates. In contrast to the Apology, which shows Socrates as a dissenter and civil disobedient, Plato's Crito shows him as an obedient citizen, refusing to escape the death sentence in order to uphold the laws of the state. In fact, the Crito features a Socrates who appears to undermine his radical stance in the Apology. Given the conflicting images of the philosopher, radical dissenter and obedient citizen, the question arises, who is the real Socrates? According to the conventional view, he was the victim of a democratic tyranny. But only in the modern era has democracy been associated with liberalism. Ancient Athenian democracy, despite its value of freedom, had no conception of individual rights and was frequently oppressive. Democracies depend upon the will of the majority for their survival. Yet the majority is not always right or just. Even in modern democracies, as the writings of Alexis de Tocqueville and John Stuart Mill remind us, freedom can be endangered by a tyranny of the majority, in which the individual is subjected to oppression by law and public opinion. Individuals who have taken a stand against the state have often done so on the basis of conscience and belief in a superordinate moral law. In the nineteenth century, Henry David Thoreau protested the extension of slavery in the United States by disobeying the law to express his moral convictions.

A similar conscientious stand is found in one of the most famous passages in the Apology, in which Socrates asserts categorically that he would disobey the state rather than abandon what he regarded as the Such a response, essentially a threat of civil disobedience, undoubtedly angered many jurors. Indeed, a more bold challenge to state authority, occurring within a court that was understood to represent the sovereign citizenry, would be difficult to find in ancient Greek history. Socrates, having already claimed a mission from God, to whom he professed to owe obedience above all, had established a basis upon which to justify resistance to state authority.

In the mid-nineteenth-century, John Stuart Mill, in his famous essay On Liberty, lauded Socrates as a saint of rationalism and viewed him as a martyr for the cause of philosophy. According to Mill, a liberal in defense of individual freedom, Athens had condemned the man who probably of all then born had deserved least of mankind to be put to death as a criminal. For Mill, a society unwilling to tolerate a high degree of freedom of thought and discussion sacrifices the values essential for the richest development of both the individual and the community. Yet, Mill conceded, we have every reason to believe that the Athenian court had honestly found him [Socrates] guilty.

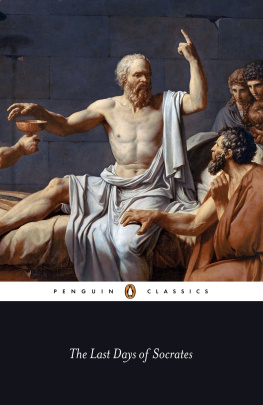

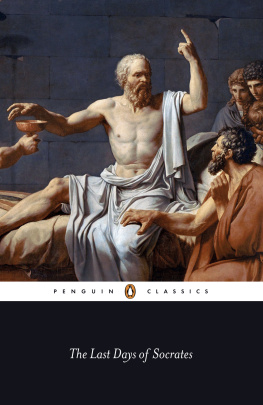

Among the most famous depictions of the philosopher is a painting by Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Socrates, first exhibited in Paris in 1787 and now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The scene depicted is from the last days of Socrates, as portrayed in Plato's Phaedo. We see Socrates sitting up on a bed surrounded by devoted followers, reaching for the cup of poison hemlock that would end his life. He is pointing upward with his other hand, as if to emphasize an idea in the philosophical discussion on the immortality of the soul that, according to Plato, had occupied him and his companions during his last days. The conflict between the philosopher and the state may be perceived in the majesty of the figure of Socrates, the painting's center, pointing up, maintaining his conviction that his commitment to his philosophic mission ranks above his duty to obey the state. The painting also depicts a consistent Socrates: By accepting the death penalty, he remains faithful to Athens while adhering to his principles.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial»

Look at similar books to Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Socrates Against Athens: Philosophy on Trial and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.