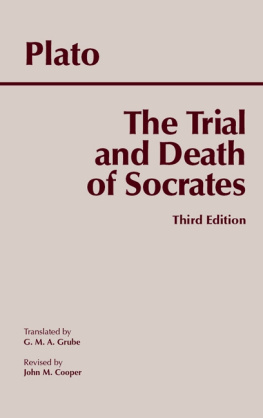

PLATO

The Trial and Death

of Socrates

Third Edition

Euthyphro

Apology

Crito

Death scene from Phaedo

Translated by

G. M. A. GRUBE

Revised by

JOHN M. COOPER

HACKETT PUBLISHING COMPANY

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2000 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 11 6 7 8 9

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P. O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, IN 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Listenberger Design & Associates

Text design by Meera Dash

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Plato.

[Dialogues. English. Selections]

The trial and death of Socrates : Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, death

scene from Phaedo / Plato; translated by G.M.A. Grube; revised by John

M. Cooper 3rd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-87220-555-X (cloth) ISBN 0-78220-554-1 (pbk.)

1. Socrates. I. Grube, G.M.A. (George Maximilian Anthony) II. Title.

B358.J82 2001

184dc21 00-047208

ISBN-13: 978-0-87220-555-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-87220-554-3 (pbk.)

ePub ISBN: 978-1-60384-648-6

PRC ISBN: 978-1-60384-660-8

CONTENTS

The translations of Platos Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, and the final scene of Phaedo presented here are taken from Hackett Publishing Companys epoch-making Plato: Complete Works (1997), prepared under my editorship. In the revised form in which George Grubes distinguished translations appear here, they present Platos wonderfully vivid and movingas well as challengingportrayal of Socrates, and of the philosophic life, in clear, contemporary, down-to-earth English that nonetheless preserves and accurately conveys the nuances of Platos and Socrates philosophical ideas. For the third edition I have added a number of new footnotes explaining various places and events in Athens, features of Greek mythology, and the like, to which Socrates or his interlocutors make reference. At a few places, mostly in the Apology, I have introduced further revisions in the translations.

John M. Cooper

At the time of his trial and execution in 399 B.C., Socrates was seventy years of age. He had lived through the Periclean age when Athens was at the pinnacle of her imperial power and her cultural ascendancy, then through twenty-five years of war with Sparta and the final defeat of Athens in 404, the oligarchic revolution that followed, and, finally, the restoration of democracy. For most of this time he was a well-known character, expounding his philosophy of life in the streets of Athens to anyone who cared to listen. His mission, which he explains in the Apology, was to expose the ignorance of those who thought themselves wise and to try to convince his fellow citizens that every man is responsible for his own moral attitudes. The early dialogues of Plato, of which Euthyphro is a good example, show him seeking to define ethical terms and asking awkward questions. There is no reason to suppose that these questions were restricted to the life of the individual. Indeed, if he questioned the basic principles of democracy and adopted towards it anything like the attitude Plato attributes to him, it is no wonder the restored democracy should consider him to have a bad influence on the young.

With the development of democracy and in the intellectual ferment of the fifth century, a need was felt for higher education. To satisfy it, there arose a number of traveling teachers who were called the Sophists. All of them taught rhetoric, the art of public speaking, which was a powerful weapon since all the important decisions were made by the assemblies of adult male citizens or in the courts with very large juries. Not surprisingly, Socrates was often confused with these Sophists in the public mind, for both of them were apt to question established and inherited values. But their differences were vital: the Sophists professed to put men on the road to success, whereas Socrates disclaimed that he taught anything; his conversations aimed at discovering the truth, at acquiring that knowledge and understanding of life and its values that he thought was the very basis of the good life and of philosophy, to him a moral as well as an intellectual pursuit. Hence his celebrated paradox that virtue is knowledge and that when men do wrong it is only because they do not know any better. We are often told that in this theory Socrates ignored the will, but that is in part a misconception. The aim is not to choose the right but to become the sort of person who cannot choose the wrong and who no longer has any choice in the matter. This is what he sometimes expresses as becoming like a god, for the gods, as he puts it in Euthyphro (10d), love the pious (and so, the right) because it is right; they cannot do otherwise and no longer have any choice at all, and they cannot be the cause of evil.

The translations in this volume give the full Platonic account of the drama of Socrates trial and death. The references to the coming trial and its charges in Euthyphro are a kind of introduction to this drama. The Apology is Platos version of Socrates speech to the jury in his own defense. In Crito we find Socrates refusing to save his life by escaping into exile. Phaedo gives an account of his discussion with his friends in prison on the last day of his life, mostly on the question of the immortality of the soul.

The influence of Socrates on his contemporaries can hardly be exaggerated, especially on Plato but not on Plato alone, for a number of authors wrote on Socrates in the early fourth century B.C. And his influence on later philosophers, largely through Plato, was also very great. This impact, on his contemporaries at least, was due not only to his theories but in large measure to his character and personality, that serenely self-confident personality which emerges so vividly from Platos writings, and in particular from his account of Socrates trial, imprisonment, and execution.

NOTE: With few exceptions, this translation follows Burnets Oxford text.

G. M. A. Grube

Socrates and Platos Socratic Dialogues

1. Benson, Hugh H., ed. Essays on the Philosophy of Socrates, Oxford, 1992. Has extensive bibliography.

2. Nehamas, Alexander. The Art of Living, Berkeley, 1998.

3. Vlastos, Gregory, ed. The Philosophy of Socrates: A Collection of Critical Essays, New York, 1971.

4.. Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher, Ithaca, N.Y., 1991.

Euthyphro

5. Cohen, S. Marc. Socrates on the Definition of Piety: Euthyphro 10a11b, Journal of the History of Philosophy 9 (1971), repr. in (3), 15876.

6. Geach, Peter T. Platos Euthyphro: An Analysis and Commentary, The Monist 50 (1966):36982.

7. Kidd, Ian. The Case of Homicide in Platos Euthyphro, in E. M. Craik, ed., Owls to Athens, Oxford, 1990, 21322.

8. MacPherran, Mark. Socratic Piety in the Euthyphro, Journal of the History of Philosophy 23 (1985), repr. in (1), 22041.

9. Mann, William. Piety: Lending Euthyphro a Hand, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58 (1998):12342.

10. Taylor, Christopher C. W. The End of the Euthyphro, Phronesis 27 (1982):10918.

Apology

11. Brickhouse, Thomas C., and Nicholas D. Smith. Socrates on Trial, Oxford, 1989.

12. Burnyeat, Myles F. The Impiety of Socrates, Ancient Philosophy 17 (1997):112.

13. Reeve, C. D. C. Socrates in the Apology, Indianapolis, 1989.

14. Stone, I. F. The Trial of Socrates, New York, 1988; with Myles F. Burnyeat, Review of

Next page