The translation and publication of the Zohar is made possible through the thoughtful and generous support of the Pritzker Family Philanthropic Fund.

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2016 by Zohar Education Project, Inc.

All rights reserved.

For further information, including the Aramaic text of the Zohar, please visit www.sup.org/zohar

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress at http://Iccn.loc.gov/2003014884

ISBN 978-0-8047-8450-4 (cloth)-

ISBN 978-1-5036-0345-5 (electronic) (vol. 11)

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free, archival-quality paper.

Designed by Rob Ehle

Typeset by El Ot Pre Press & Computing Ltd., Tel Aviv,

in 10.5/14 Minion.

Academic Committee

for the Translation of the Zohar

Daniel Abrams

Bar-Ilan University

Joseph Dan

Hebrew University

Rachel Elior

Hebrew University

Asi Farber-Ginat

University of Haifa

Michael Fishbane

University of Chicago

Pinchas Giller

American Jewish University

Amos Goldreich

Tel Aviv University

Moshe Hallamish

Bar-Ilan University

Melila Hellner-Eshed

Hebrew University

Boaz Huss

Ben-Gurion University

Moshe Idel

Hebrew University

Esther Liebes

Gershom Scholem Collection, Jewish National and University Library

Yehuda Liebes

Hebrew University

Bernard McGinn

University of Chicago

Ronit Meroz

Tel Aviv University

Charles Mopsik,

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique

Michal Oron

Tel Aviv University

Haviva Pedaya

Ben-Gurion University

Bracha Sack

Ben-Gurion University

Elliot R. Wolfson

New York University

Arthur Green

Co-Chair

Brandeis University

Rabbi Yehiel Poupko

Co-Chair

Jewish Federation of Chicago

Margot Pritzker

Chair, Zohar Education Project, Inc.

Daniel C. Matt

Translator, Zohar Education Project, Inc.

Contents

JOEL HECKER |

Midrash ha-Nelam al Shir ha-Shirim

Midrash ha-Nelam on Song of Songs |

Midrash ha-Nelam al Rut

Midrash ha-Nelam on Ruth |

Midrash ha-Nelam al Eikhah

Midrash ha-Nelam on Lamentations |

Zohar al Shir ha-Shirim

Zohar on Song of Songs |

Matnitin

Our Mishnah |

Tosefta

Addenda |

Sitrei Torah

Secrets of Torah |

This eleventh volume in the series is the first to present a variety of Zoharic texts, reflecting the range of genres within the Zoharic library. Many of these sections first appeared in print in the publication that was titled Zohar adash, or New Zohar; this title is misleading, however, in that the volume comprises some of the earliest Zoharic material.

The first chapter, Midrash ha-Nelam on Song of Songs, is quite short. Despite its name, it does not actively interpret the Song of Songs, aside from the opening treatment of the mystical import of the kiss, and its second homily that interprets the large letter (shin) at the beginning of that biblical book. Most likely, it was originally an introduction to a larger work, either lost or intended but never realized. Like Midrash ha-Nelam on the Torah (see Preface to Volume 10), Midrash ha-Nelam on Song of Songs is populated by rabbis who are not among Rabbi Shimon son of Yoais group in the Main Body of the Zohar (see Volumes 19). Unlike Midrash ha-Nelam on the Torah, almost all of this fragment appears in Aramaic; and much of it is written with the standard theosophic symbolism that one finds in the epic layer of the Zohar. However, the last quarter of this work is an extended non-sefirotic interpretation of Ecclesiastes 12, drawing upon the classic style and content of its midrashic commentators.

Chapter Two, Midrash ha-Nelam on Ruth, encompasses a wide range of Zoharic interests. Here, too, the text is written mostly in Aramaic, its broad array of rabbinic figures is typical of Midrash ha-Nelam, andas is characteristic of that Zoharic stratumthe focus is on aspects of the soul, its origin, and its fate. Much of the interpretive style is non-kabbalistic, although proto-kabbalistic and full-blown sefirotic imagery are also in abundance.

While the text interprets a substantial portion of the Book of Ruth, interspersed throughout are many other issues, including: near-death journeys to the afterlife; the chambers of hell; commentaries on the Shema, Grace after Meals, and other sections of the traditional liturgy, including several medieval liturgical innovations. Among them are the Zoharic prescription to repeat the final three words of the Shema (apparently referring to the last three words rather than the ultimately prevailing practice of repeating the last two words and the first word of the succeeding blessing); and the recital of the Qaddish prayer on behalf of the deceased. Other highlights include the story of the ten martyrs; reference to a threefold method of interpreting the Torah (although later traditions altered the text to conform to the well-known fourfold method, called PaRDeS); and the kabbalistic meaning of rules for dining. Since the ancient rabbis view Ruth as the first convert to Judaism, the Zohars kabbalists use her story as a vehicle to think about Gentiles and, often, to polemicize against them.

Midrash ha-Nelam on Ruth was known by the editors of the first printed editions of the Zohar, but (aside from small passages scattered throughout the Cremona printing of 1558) was not included in them. Similarly, major kabbalists in the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries did not always consider it to be part of the Zoharic corpus. It was first published as an independent work in Thiengen in 1559 under the titles Yesod Shirim and Tappuei Zahav, not gaining the name Midrash ha-Nelam al Rut until it was republished in Venice in 1565. Ultimately, it was incorporated into the 1658 printing of Zohar adash. Both before and after that printing, the work carried other titles, such as Midrash Rut and Sefer Midrash Rut he-adash.

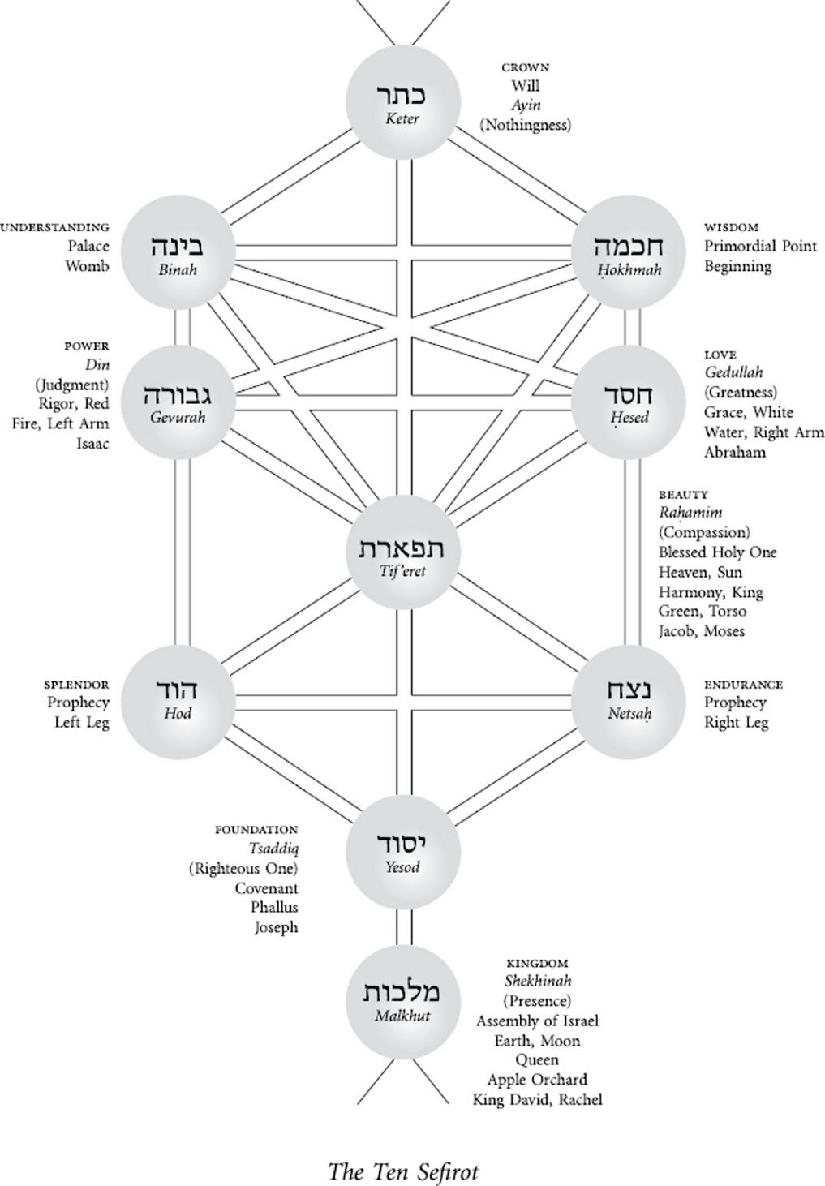

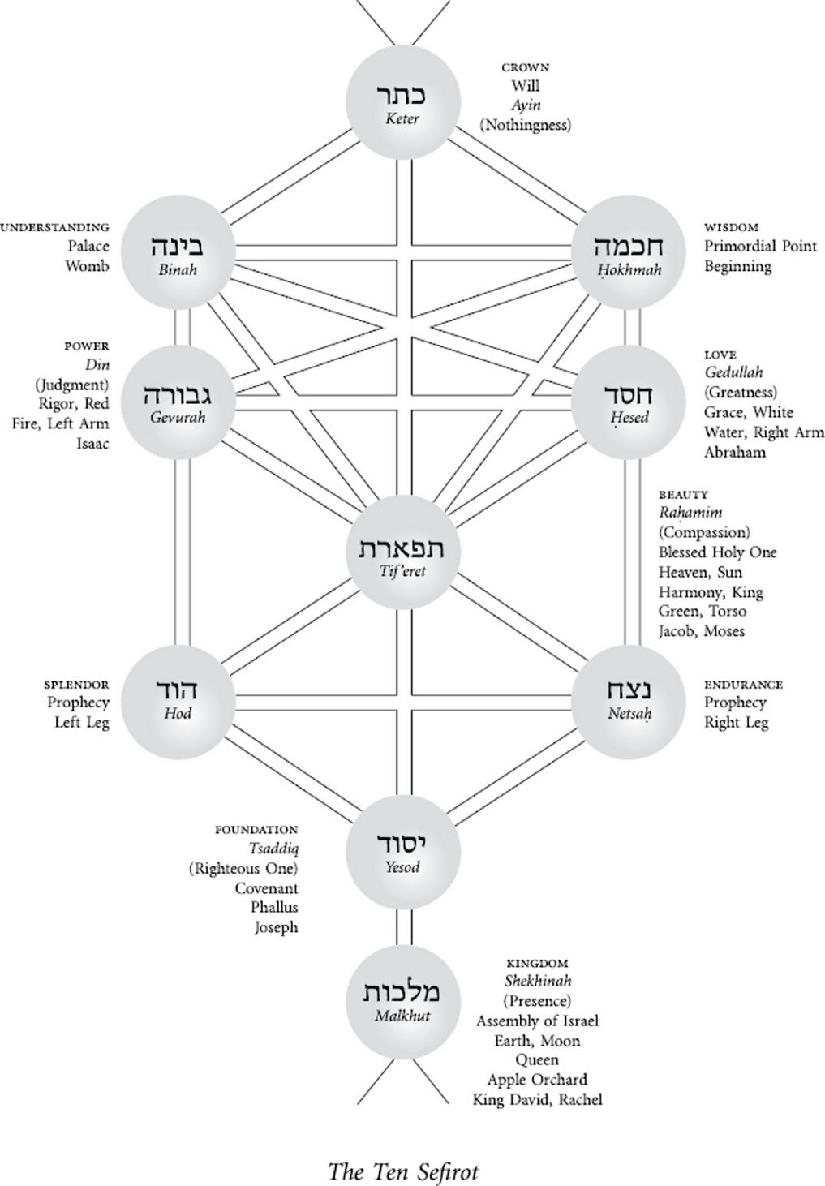

The third chapter, Midrash ha-Nelam on Lamentations, is notable for its pathos-filled debate between the inhabitants of Israel and the inhabitants of Babylona poignant competition in which each side argues that it has suffered more as a result of the destruction of the Temple. The inhabitants of Israel prevail, and then they express their anguish in their abandonmentas if having been orphaned by their Divine Father and Mother above. Ultimately, this serves as a Jewish reframing of the notion of a Holy Family, and as a subtle polemic against Christianity. Tiferet and Shekhinah appear here as Father and Mother, with Israel as the Holy Childin contrast to the Christian triad of God the Father, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus. The hybrid qualities of