Chapter One

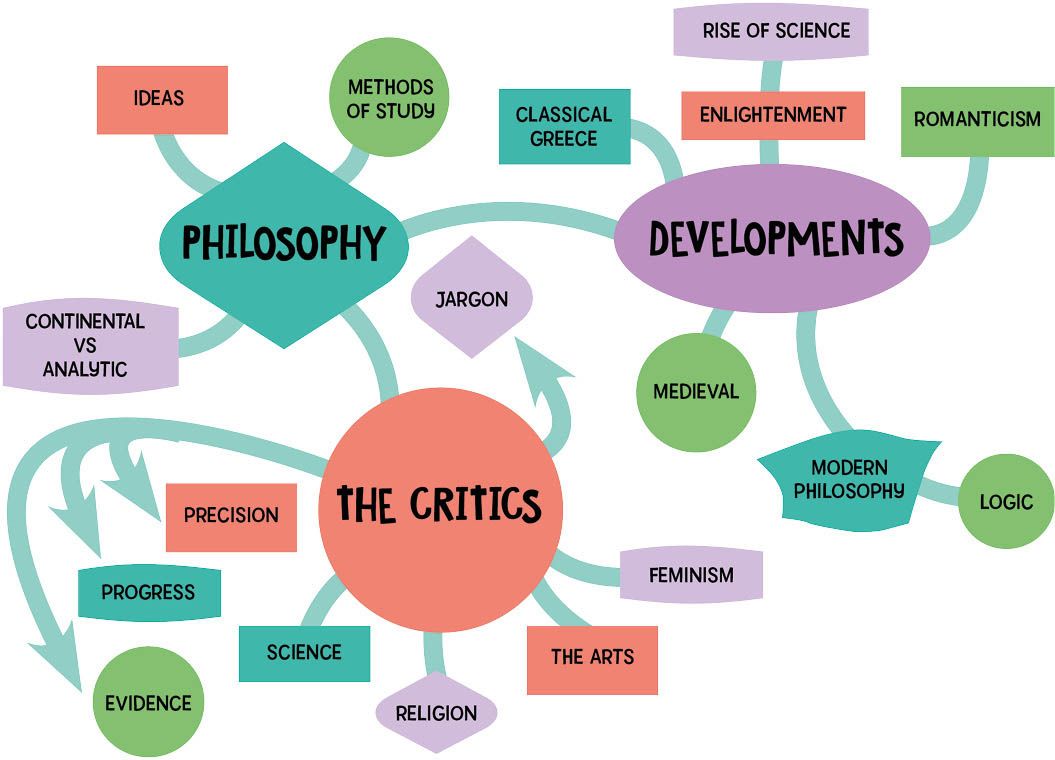

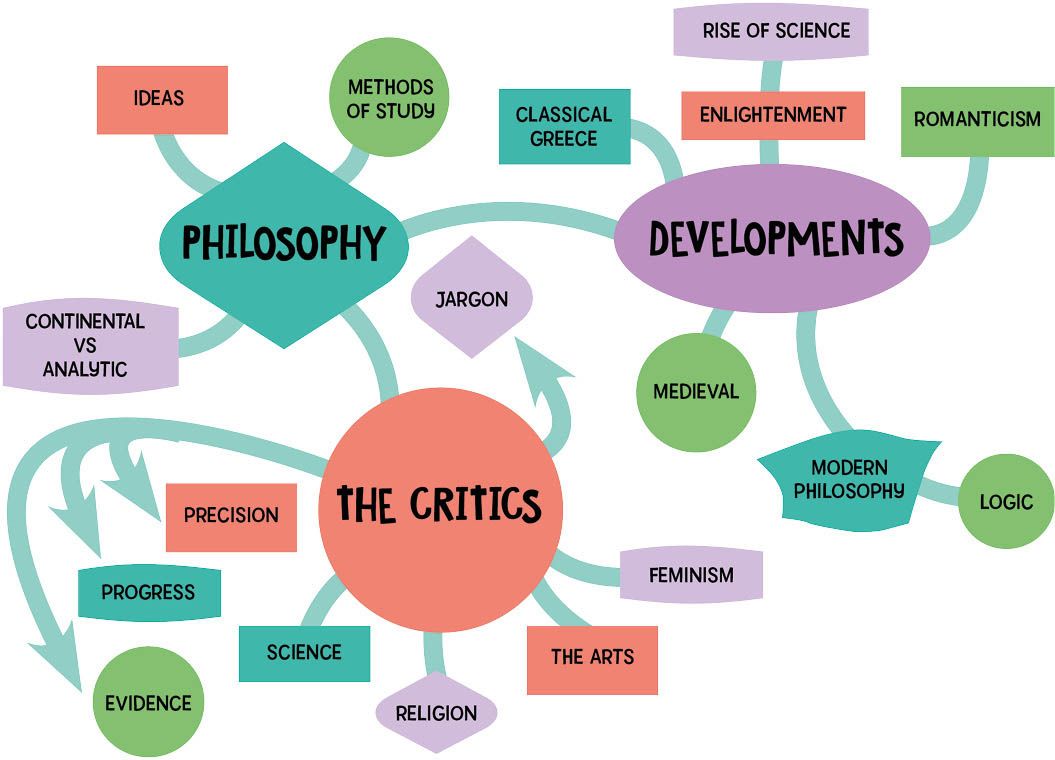

What is Philosophy?

Defining Philosophy Methods of Study The Critics Philosophy and Real Life

Defining philosophy

If you sit quietly at the back of a philosophy class you will hear people expressing views about fairly abstract matters. They are not, however, merely swapping opinions. Not only do their listeners demand reasons for opinions, but the speakers themselves focus more on their reasons than on their opinions, and may even offer objections to their own views. The study of reasons for opinions is at the centre of philosophy.

Of course, a rational discussion of law or gardening is also interested in the reasons given for opinions, but philosophy also has a distinctive subject matter. Philosophers try to understand the world. However, many other disciplines such as physics, chemistry, statistics, biology, literature, geography and history seek the same thing.

Philosophers Questions

Philosophers step back from these studies, and ask more general questions:

- What is an object?

- a law?

- a number?

- a life?

- a person?

- a society?

- a story?

- an event?

Each of these concepts is taken for granted by ordinary speakers, until we wonder exactly what each of them means and that is where the puzzles, ambiguities and vagueness begin. Other disciplines must take such normal terminology for granted, but philosophy tries to take nothing for granted.

Continental vs Analytic Philosophy

About two hundred years ago Western philosophy divided into two camps. The continental school , flourishing most notably in Germany and France, sees philosophy as closely allied to literature and psychology, and focuses on major concepts that offer broad insights. The analytic school , predominant in the United Kingdom and the United States, pays more attention to the physical sciences and to logic, and seeks precision and clarity by means of definitions and proofs.

Ideas

Philosophers focus on the key concepts that are the basis of our thinking. Philosophy does not simply study the problematic nature of ordinary ideas. Ideas are in our minds, but they refer to the outside world, and the aim is to think more clearly in order to understand the world more clearly. Philosophy aims for clarity, but its key feature is its highly-generalised nature. Specialists investigate the physical world, or the past, or how to improve our practical lives, but philosophy aims to get the framework of our understanding right. We all want to do the right thing, and to be good people, but what makes something right or good? We want to live in a just society, but what is justice?

We might therefore define philosophy as trying to understand reality and human life in very general terms, by studying key ideas in our thinking, to form a picture guided by good reasons . Most of the famous works of philosophy fit that description, apart from a few misfits. Philosophers are inclined to question everything, even the nature of their own subject.

| IDEAS |

|---|

| in our minds |

| refer to the outside world |

| PHILOSOPHY |

|---|

| understanding reality and human life |

Enlightenment

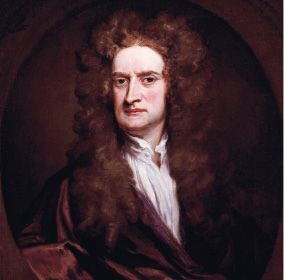

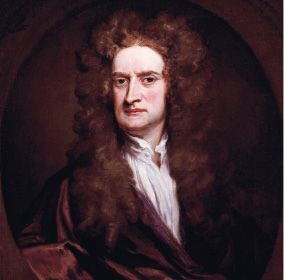

The years 1620 to 1800 were the period of the European Enlightenment, sometimes called The Age of Reason. It was an age of classicism in architecture, and a new mechanical inventiveness in industry. Though some philosophers such as David Hume were pessimistic about the power of reason, the dominant view was that our understanding and way of life could become much more rational (see ). Isaac Newton had explained the movement of the solar system in one short equation, and a rational account of all of reality seemed attainable. In the 1780s, Immanuel Kant made a notable contribution by offering a theory of morality, built on nothing more than consistency and rationality in our principles of behaviour.

Philosophy acquired great prestige in the Age of Reason. When philosophy allied itself with the new science, it looked like a winning team which could finally make human life a rational affair.

THE AGE OF REASON

David Hume pessimistic

Isaac Newton an equation for the solar system

Immanuel Kant rational theory of morality

Romanticism

But just as rational and scientific philosophy was poised for victory, rebellions arose, mainly among artists and writers. The cold classicism and the logical mode of life seemed to neglect the most important part of our lives our feelings. In the early nineteenth century, important philosophers continued to flourish, but in a more cautious vein than their bolder Enlightenment predecessors.

With the discoveries of Isaac Newton, it seemed that everything could now be explained in rational terms.

| Philosophers of the Enlightenment |

|---|

| Britain | Thomas Hobbes (15881679) George Berkeley (16851753) John Locke (16321704) David Hume (17111776) |

| France | Ren Descartes (15961650) Jean-Jacques Rousseau (17121778) |

| Germany | Gottfried Leibniz (16461716) Immanuel Kant (17241804) |

The Women of Philosophy

The history of philosophy is, without doubt, dominated by men. Hypatia of Alexandria was a notable female philosopher in the ancient world, and in the Enlightenment a number of women engaged in high-level philosophical correspondence and wrote significant books. The idea that women should have full equality as citizens began to emerge in the nineteenth century, and women wrote forcefully on that topic. It is only, though, when women gained the right to study at universities that they became major contributors to philosophy. Nowadays women have, at least in formal terms, full access to all areas of philosophical activity.

The University

In modern universities there is less emphasis on taking wider views of knowledge, because specialists are investigating smaller parts of the project, but every philosopher is motivated by interests wider than their own narrow specialism, and always bear these in mind. Philosophy can even be seen as a way of life, rather than an academic subject, but the aim is still to place ones life within a bigger picture.

Methods of Study

Most philosophers agree on the need for rationality, clear concepts, general truths and a big picture but they disagree about the appropriate methods.

In ancient Greece, philosophy was mostly studied through conversation in the famous schools, with books as occasional by-products. |

In medieval Europe, the main focus was on explaining the famous surviving ancient texts, especially those by Aristotle. With the arrival of printing, it became possible to give new books a wide circulation, and philosophy centred on written debate between leading scholars, who often lived in isolation from one another. |

The rise of science divided philosophers: some of them embracing the new physical discoveries as an expansion of traditional philosophy, while others asserted its separateness, and its concern with thought, abstractions and eternal truths. |

The emergence of many new universities in the nineteenth century greatly changed the practice of philosophy, and today leading philosophers mostly spend their careers within university departments. The modern university seminar resembles the conversations in ancient schools, but there are also innumerable papers published in journals, with critical responses from colleagues, and regular international conferences which focus on the specialist topics within philosophy. |