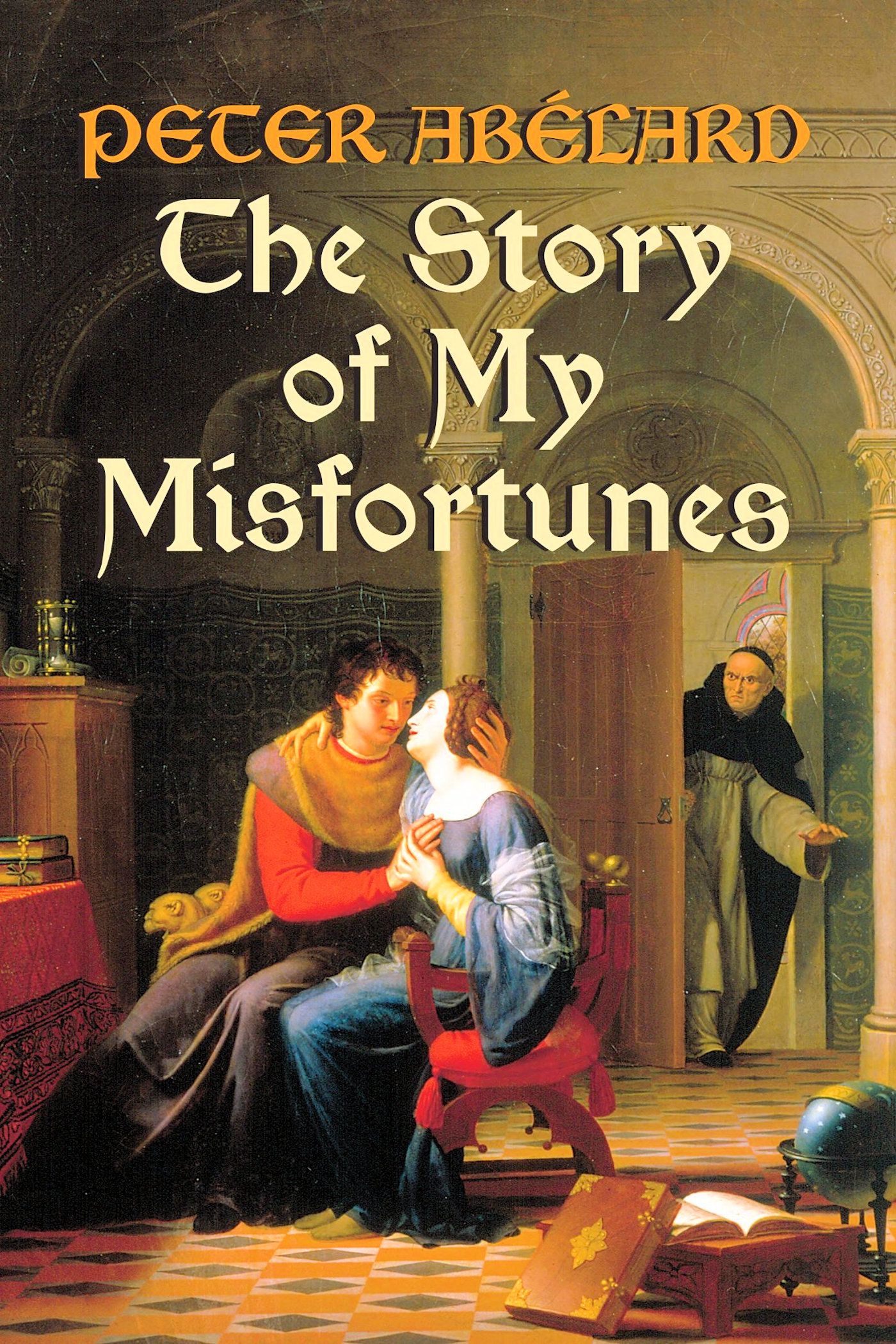

Peter Abelard - The Story of My Misfortunes

Here you can read online Peter Abelard - The Story of My Misfortunes full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Dover Publications, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Story of My Misfortunes

- Author:

- Publisher:Dover Publications

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Story of My Misfortunes: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Story of My Misfortunes" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Story of My Misfortunes — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Story of My Misfortunes" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This Dover edition, first published in 2005, is an unabridged republication of Historia Calamitatum: The Story of My Misfortunes, published by Thomas A. Boyd, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1922. The Historia Calamitatum was originally written c. 1132.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Abelard, Peter, 1079-1142.

[Historia calamitatum. English]

The story of my misfortunes / Peter Abelard ; translated by Henry Adams Bellows ; introduction by Ralph Adams Cram.

p. cm.

Originally published: Historia calamitatum. Saint Paul : T.A. Boyd, 1922.

9780486164519

1. Abelard, Peter, 1079-1142. 2. Abelard, Peter, 10791142-Relations with women. 3. Authors, Latin (Medieval and modern)FranceBiography. 4. TheologiansFranceBiography. I. Bellows, Henry Adams, 1885-1939. II. Title.

PA8201.H4 2005

I89.4dc22

2005040139

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

44401502

www.doverpublications.com

Facsimile of the original manuscript

THE Historia Calamitatum of Peter Ablard is one of those human documents, out of the very heart of the Middle Ages, that illuminates by the glow of its ardour a shadowy period that has been made even more dusky and incomprehensible by unsympathetic commentators and the ill-digested matter of source-books. Like the Confessions of St. Augustine it is an authentic revelation of personality and, like the latter, it seems to show how unchangeable is man, how consistent unto himself whether he is of the sixth century or the twelfthor indeed of the twentieth century. Evolution may change the flora and fauna of the world, or modify its physical forms, but man is always the same and the unrolling of the centuries affects him not at all. If we can assume the vivid personality, the enormous intellectual power and the clear, keen mentality of Ablard and his contemporaries and immediate successors, there is no reason why The Story of My Misfortunes should not have been written within the last decade.

They are large assumptions, for this is not a period in world-history when the informing energy of life expresses itself through such qualities, whereas the twelfth century was of precisely this nature. The antecedent hundred years had seen the recovery from the barbarism that engulfed Western Europe after the fall of Rome, and the generation of those vital forces that for two centuries were to infuse society with a vigour almost unexampled in its potency and in the things it brought to pass. The parabolic curve that describes the trajectory of Mediaevalism was then emergent out of chaos and old night and Ablard and his opponent, St. Bernard, rode high on the mounting force in its swift and almost violent ascent.

Pierre du Pallet, yclept Ablard, was born in 1079 and died in 1142, and his life precisely covers the period of the birth, development and perfecting of that Gothic style of architecture which is one of the great exemplars of the period. Actually, the Norman development occupied the years from 1050 to 1125 while the initiating and determining of Gothic consumed only fifteen years, from Bury, begun in 1125, to Saint-Denis, the work of Abbot Suger, the friend and partisan of Ablard, in 1140. It was the time of the Crusades, of the founding and development of schools and universities, of the invention or recovery of great arts, of the growth of music, poetry and romance. It was the age of great kings and knights and leaders of all kinds, but above all it was the epoch of a new philosophy, refounded on the newly revealed corner stones of Plato and Aristotle, but with a new con- , tent, a new impulse and a new method inspired by Christianity.

All these things, philosophy, art, personality, character, were the product of the time, which, in its definiteness and consistency, stands apart from all other epochs in history. The social system was that of feudalism, a scheme of reciprocal duties, privileges and obligations as between man and man that has never been excelled by any other system that society has developed as its own method of operation. As Dr. De Wulf has said in his illuminating book Philosophy and Civilization in the Middle Ages (a volume that should be read by anyone who wishes rightly to understand the spirit and quality of Mediaevalism), the feudal sentiment par excellence is the sentiment of the value and dignity of the individual man. The feudal man lived as a free man; he was master in his own house; he sought his end in himself ; he wasand this is a scholastic expression, propter seipsum existens: all feudal obligations were founded upon respect for personality and the given word.

Of course this admirable scheme of society with its guild system of industry, its absence of usury in any form and its just sense of comparative values, was shot through and through with religion both in faith and practice. Catholicism was universally and implicitly accepted. Monasticism had redeemed Europe from barbarism and Cluny had freed the Church from the yoke of German imperialism. This unity and immanence of religion gave a consistency to society otherwise unobtainable, and poured its vitality into every form of human thought and action.

It was Catholicism and the spirit of feudalism that preserved men from the dangers inherent in the immense individualism of the time. With this powerful and penetrating coordinating force men were safe to go about as far as they liked in the line of individuality, whereas today, for example, the unifying force of a common and vital religion being absent and nothing having been offered to take its place, the result of a similar tendency is egotism and anarchy. These things happened in the end in the case of Mediaevalism when the power and the influence of religion once began to weaken, and the Renaissance and Reformation dissolved the fabric of a unified society. Thereafter it became necessary to bring some order out of the spiritual, intellectual and physical chaos through the application of arbitrary force, and so came absolutism in government, the tyranny of the new intellectualism, the Catholic Inquisition and the Puritan Theocracy.

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, however, the balance is justly preserved, though it was but an unstable equilibrium, and therefore during the time of Ablard we find the widest diversity of speculation and freedom of thought which continue unhampered for more than a hundred years. The mystical school of the Abbey of St. Victor in Paris follows one line (perhaps the most nearly right of all though it was submerged by the intellectual force and vivacity of the Scholastics) with Hugh of St. Victor as its greatest exponent. The Franciscans and Dominicans each possessed great schools of philosophy and dogmatic theology, and in addition there were a dozen individual lines of speculation, each vitalized by some one personality, daring, original, enthusiastic. This prodigious mental and spiritual activity was largely fostered by the schools, colleges and universities that had suddenly appeared all over Europe. Never was such activity along educational lines. Almost every cathedral had its school, and many of the abbeys as well, as for example, in France alone, Cluny, Citeaux and Bec, St. Martin of Tours, Laon, Chartres, Rheims and Paris. To these schools students poured in from all over the world in numbers mounting to many thousands for such as Paris for example, and the mutual rivalries were intense and sometimes disorderly. Groups of students would choose their own masters and follow them from place to place, even subjecting them to discipline if in their opinion they did not live up to the intellectual mark they had set as their standard. As there was not only one religion and one social system, but one universal language as well, this gathering from all the four quarters of Europe was perfectly possible, and had much to do with the maintenance of that unity which marked society for three centuries.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Story of My Misfortunes»

Look at similar books to The Story of My Misfortunes. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Story of My Misfortunes and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.