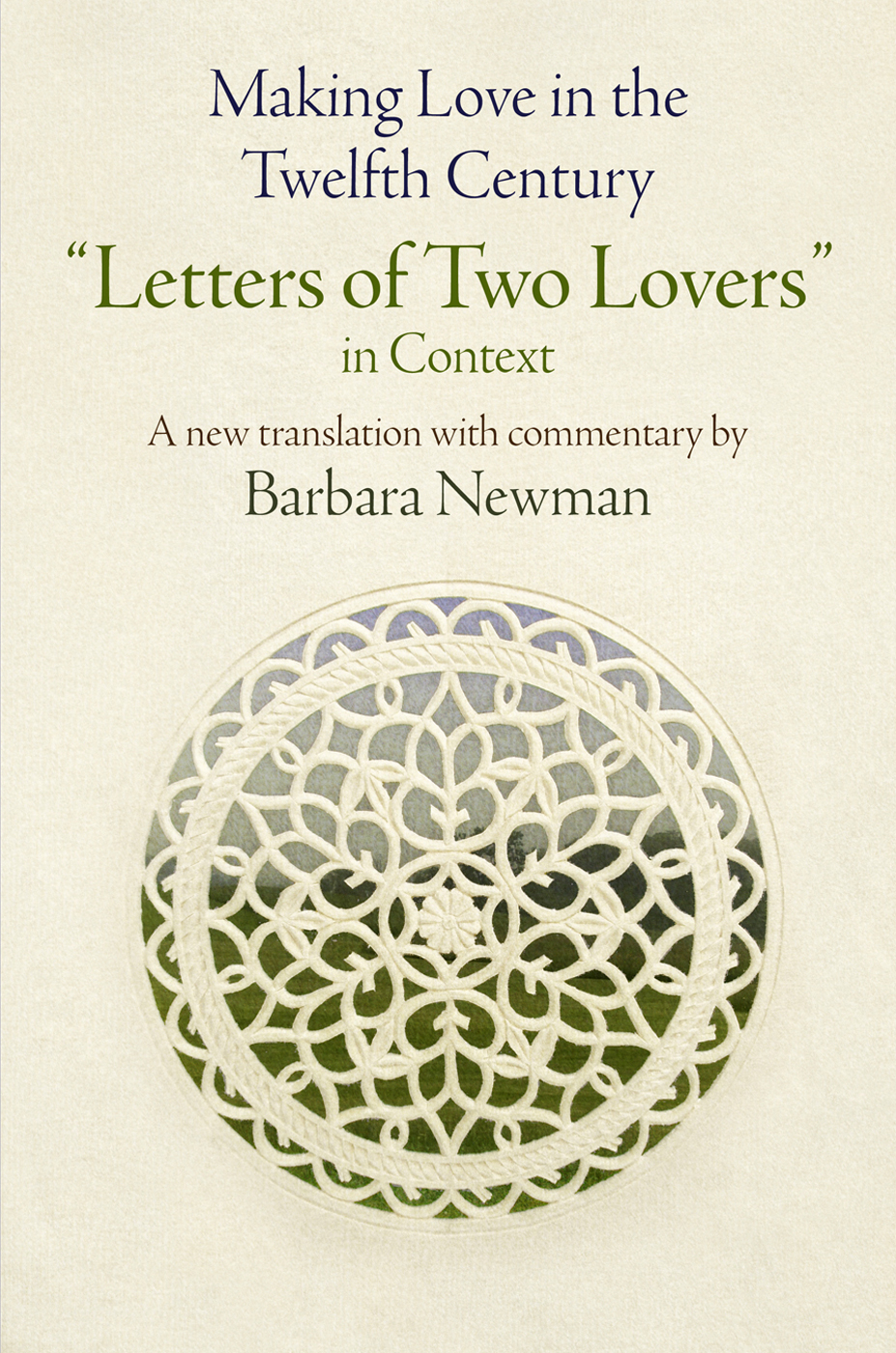

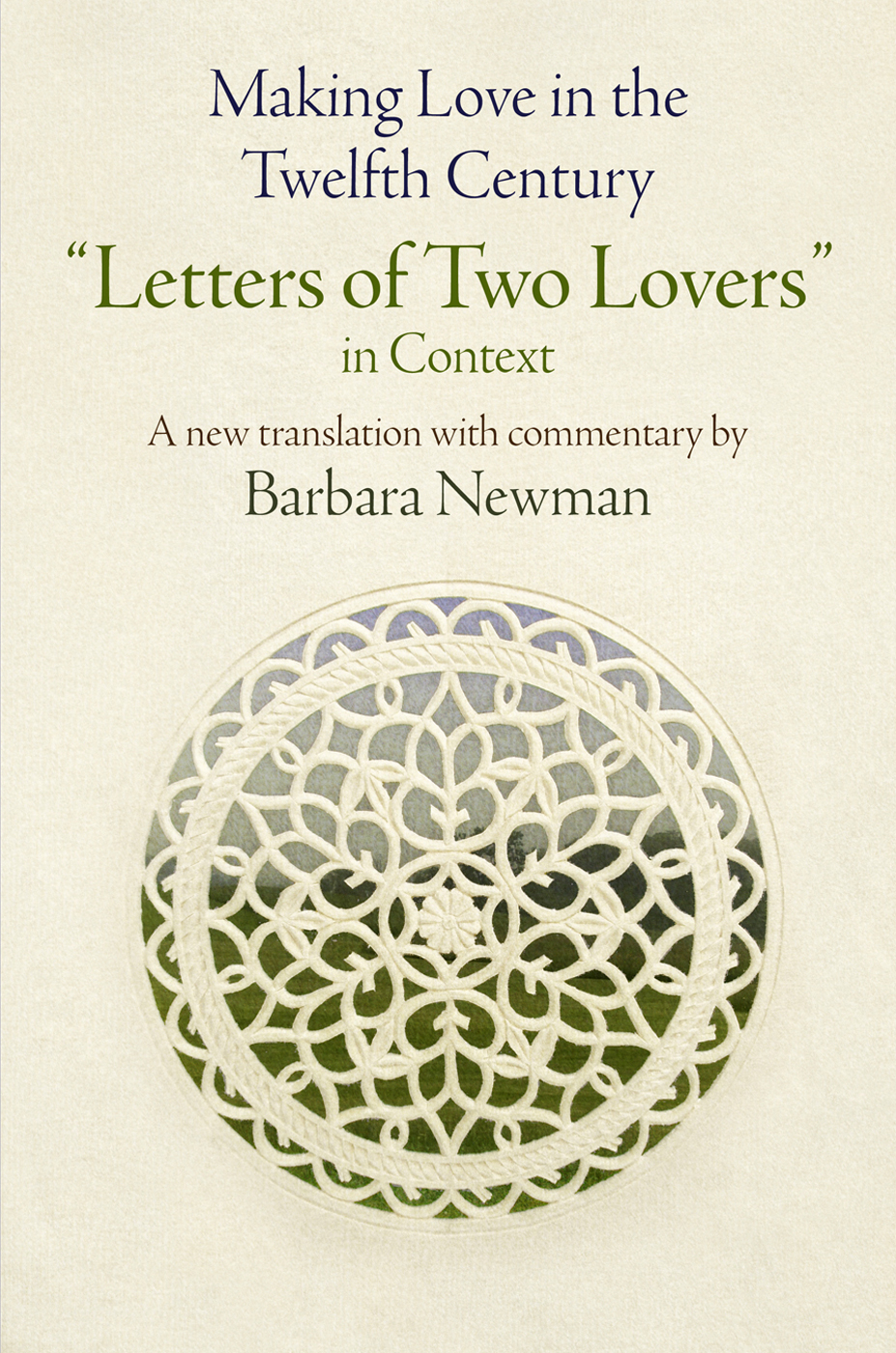

Making Love in the Twelfth Century

THE MIDDLE AGES SERIES

Ruth Mazo Karras, Series Editor

Edward Peters, Founding Editor

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

Making Love in the Twelfth Century

Letters of Two Lovers in Context

A new translation with commentary by

Barbara Newman

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2016 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Newman, Barbara, author, translator. | Epistolae duorum amantium. Commentary on (work): | Tegernseer Briefsammlung des 12. Jahrhgunderts. Selections. Commentary on (work): |Carmina Ratisponensia. Selections. Commentary on (work):

Title: Making love in the twelfth century : letters of two lovers in context / a new translation with commentary by Barbara Newman.

Other titles: Middle Ages series.

Description: Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press. [2016] | Series: The Middle Ages series | Contains translations from Latin or German. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015038849 | ISBN 9780812248098 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Love-lettersEuropeHistoryTo 1500. | Latin letters, Medieval and ModernHistory and criticism. | Letter writingEuropeHistoryTo 1500. | LoveEuropeHistoryTo 1500. | Abelard, Peter, 10791142. | Hlose, approximately 10951163 or 1164. | Epistolae duorum amantium | Tegernseer Briefsammlung des 12. Jahrhunderts. Selections. | Carmina Ratisponensia. Selections.

Classification: LCC PN6140.L7 N49 2016 | DDC 876'.03dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038849

R. dilectissimo suo,

magistro virtutibus, magistro moribus,

viventium carissimo

et super vitam diligendo

Contents

Preface

Nine hundred years ago in the north of France, a man and a woman fell in love and began to exchange letters. The man was a philosopher, a famous teacher who, to the delight of his beloved, had also drunk from the fountain of poetry. The woman, his student, was in her lovers eyes a great beauty. She was also eloquent, passionately devoted to her teacher, and morally earnest to the nth degree, inspiring him to call her the only disciple of philosophy among all the girls of our age. Teaching must have been a competitive sport in their milieu, for one of her letters is a victory ode, congratulating her lover on his academic triumph over a rival. The couples letters reveal little beyond this about their identity or individual circumstances, for they come down to us only in a single late, painfully abridged manuscript. We know the name of its compiler and scribe, but the lovers themselves remain anonymous, without even initials to hint at their names.

By reading these fragmentary letters in their historical context, we can glean a few more details. For instance, the woman had obviously been educated in a convent. She could have acquired her excellent Latin and her familiarity with classical authors, along with her deep knowledge of Scripture and liturgy, in no other milieu. Yet she was not a nun, far less a princess or lady of high ranka fact that makes her unique among the handful of female correspondents known from this period. The discourse of virtue flows readily from her stylus, but one particular virtuechastityis nowhere mentioned. The only vows she acknowledges are those of love. She speaks constantly of amicitia (friendship) and dilectio (personal love), but also of amor (erotic love) and desiderium (desire) with its flames. Her teacher, though certainly a cleric, seems not to be a monk or priest. His biblical allusions are fewer than hers, but his citations of Ovid more frequent. The themes of the correspondence are those of lovers everywhere (praise of each others beauty and brilliance, cries of passion, fear of abandonment, professions of fidelity and eternal love), with a strong mix of period motifs (the duties of friendship, the danger of envious foes, the fear of scandal).

Despite the lovers florid mutual compliments, the course of their affair was anything but smooth. Judging from a poem the man composed to celebrate their first anniversary, which falls about two-thirds of the way through the correspondence, they remained together for about a year and a half, though for much of that time they were separated and unable to meet. The woman seems to have found this long-distance relationship more troubling than her partner did, for she alternates between protesting her changeless constancy and accusing him of faithlessnessby which she means not loving another, but forgetting her and reneging on his promised visits. He defends himself fervently, insisting that his love has not changed except to grow even strongeryet he admits to becoming more cautious as he tries to stifle dangerous rumors. After at least two bitter quarrels and hard-won reconciliations, the correspondence simply ends. We do not know how or why, for the exchange as we have it is maddeningly oblique. The sequence of letters in the manuscript does not preserve the order in which they were sent. Some are almost certainly missing, and a great many have been deliberately abridged, for the scribe makes it clear that his interest lies in fine specimens of epistolary style, not in the lovers story. They were probably just as anonymous for him as they are for us. The manuscript from which he copied their letters, as any novelist could predict, has disappeared.

What happened to these lovers when their affair came to an end? Could some crime of passion have parted them? Did they marry each other? Or could they have entered religious life? One true, simple, and infuriating answer to such questions is we dont know. A different answerpossibly true, not at all simple, satisfying to some but infuriating to othersis yes to all of the above.

Were the mysterious lovers, in fact, Abelard and Heloise?

Epistolae duorum amantium and the Second Authenticity Debate

The reader will guess that I am not the first to pose that question.

These letters are known to the scholarly world as Epistolae duorum amantium (EDA or Letters of Two Lovers) from the title given them by their scribe, one Johannes de Vepria or Jean de Voivre.

Knsgen and his publisher may have aimed to tantalize readers by giving his edition the subtitle Briefe Abaelards und Heloises? But this was an honest question, for he concluded that the anonymous writers must have been a couple like Abelard and Heloise without presenting their authorship as fact. Alexander Popes Eloisa to Abelard (1717), an Ovidian heroic epistlecomposed in the same genre that so deeply influenced the real Heloiseis but the most famous of the innumerable poems, songs, novels, plays, paintings, and more recently, operas and films inspired by the couple. In 1817, Josephine Bonaparte had their bodies transferred to the new Pre Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, where their tomb rapidly became a shrine. It was only natural that such a romantic legend should drive historians, fired by the new spirit of positivism, to take a more skeptical look at their Latin letters.

Next page