Copyright 2021 by Reuben Jonathan Miller

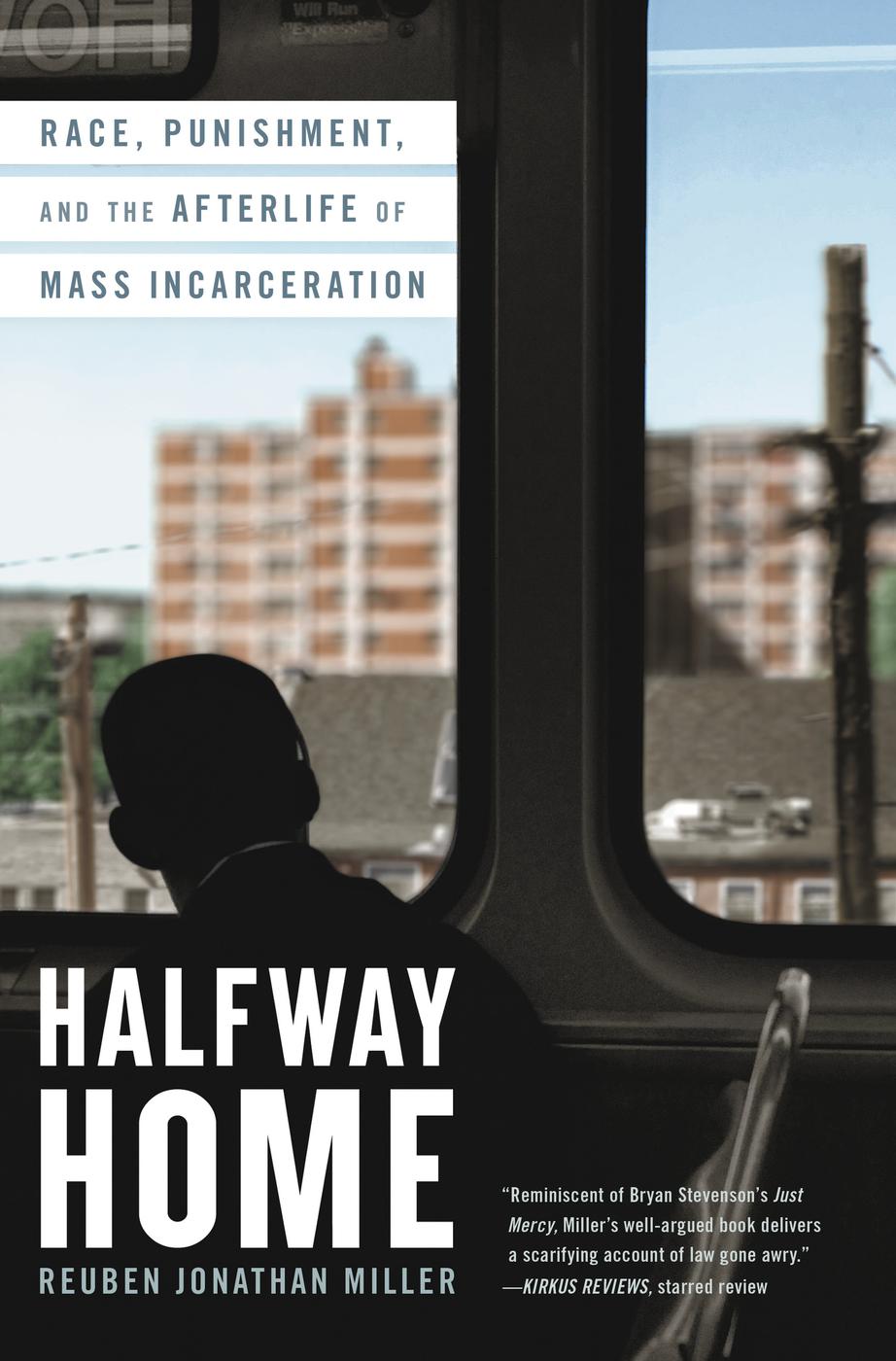

Cover design by Kirin Diemont

Cover photograph by Mike Voss / Arcangel

Cover copyright 2021 Hachette Book Group

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

facebook.com/LittleBrownandCompany

twitter.com/LittleBrown

First ebook edition: February 2021

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-45149-9

E3-20210108-DA-NF-ORI

For Dorothy Jean and Tommy.

For George Walter, and all our saints.

And for Kyle, who slept too early.

For Hyacinth and Mary, and for Michele,

for all that they have done.

For Janice and for our children, with all the love that I have.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

I d grown accustomed to the sounds of buzzers and gray steel doors shutting and locking behind me. Its not like in the movies. The men who live there dont flinch when the gates close. The smell of must, instant coffee, hastily brushed teeth, unwashed jumpsuits, and stomach flu tells you precisely where you are. But learning how to get around a place like this is an altogether different question. Underground passageways, some narrower and dingier than others, connect ten divisions sprawled across a ninety-six-acre compound. The campus feels stitched together. Red-brick, whitewashed, and gray stone buildings, each built at a different architectural moment, stretch up several stories before stretching out a full square mile; theyre connected by sidewalk trails, the yard, and hints of green space. Lines leading into the main dormitories wrap around the block-long brick-and-concrete walls that separate men and women in cages from their loved ones. The pace inside is slow but dizzying. A Frankenstein of a jail complex, Cook County is a patchwork of construction projects and racial politics lurching from the eighteenth century into the twenty-first.

In 1779, Chicagos black immigrant founder, trapper and fur trader Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, was arrested by the British under suspicion of intercourse with the enemy.

Two centuries later, the psychologist Winston Moore, a bear of a man nicknamed Buddha by his colleagues, was appointed Americas first black Warden. Presiding over the notorious and poorly run Cook County Jail, Moore was given the task of reforming and expanding it.

That Moore was tried in the courthouse he helped to fill reveals much about American so-called race relations and the uneven administration of what weve misrecognized as justice. The word justice suggests some harm repaired or some truth revealed, but 95 percent of all court cases end in a plea deal after a person has spent anywhere from several weeks to several years in a cage. Of the 2.3 million people who are incarcerated, 40 percent are black, 84 percent are poor, and half have no income at all.

This is the weight and history of punishment in the United States, which poor people encounter before their arrests. To live through mass incarceration is to take part in a lineage of control that can be traced from the slave ships, through the Jim Crow South, to the ghettos of the North, and to the many millions of almost-always-filled bunk beds in jails and prison cells that make the United States the worlds leading jailer.

Neither Moore nor du Sable fully rebounded from their encounters with the law. This is because a history of arrest, whether it leads to a conviction or not, whether the conviction is overturned or not, is just like any other history, especially those told inaccurately. It need not be well understood, or even true, to exercise power. The history of punishment and black incarceration, of racism and the production of race, the whole history of crime and criminality haunt the people weve accused of crimes. It whispers into the ears of prospective employers and landlords, urging them to reject applications. And it whispers into the ears of grandmothers and girlfriends as they make life-or-death decisions on behalf of their loved ones, forcing them to withhold a couch to sleep on or risk eviction to help them because the state has labeled the people they care for most criminals. Mass incarceration has changed the social life of the city. It has filtered into the most intimate relationships and deformed the contours of American democracy, one poor (and most often) black family at a time.

Winston Moore was a member of the political elite, a man who, through his long list of connections, could avoid getting caught in the leviathans teeth. He was arrested and fired twice, once under scandal and once for criticizing his employer. But Moore, who could hire an attorney, did not spend a single night in jail. And while you can ask any Illinois governor if the occupant of that office can survive a brush with the law, but he somehow found the time between his trial and incarceration to appear on Donald Trumps reality-TV show Celebrity Apprentice. Trump granted Blagojevich clemency in the third year of his presidency. If we really wish to know how justice is administered, James Baldwin tells us in No Name in the Street, we must go to the unprotectedthose, precisely, who need the laws protection most!and listen to their testimony. Ask the wretched how they fare in the halls of justice, he writes, and then you will know, not whether or not the country is just, but whether or not it has any love for justice, or any concept of it.

Let us go, then, to hear the stories that only the people weve labeled criminals can tell us about their lives. But we should not just go to the obvious places where the poor come into contact with the law, like the jails and prisons where they languish or the street corners where police detain them. To fully understand mass incarceration, we must go to the neighborhoods that hemmed them in long before they occupied cages, the same places that serve as their confines for years after they return. We must wait with them for a space to open in the halfway house or in the shelter, because the laws and policies that the U.S. government has enacted ensure there is no place for them to go. We must sit in the homes of the parents, lovers, and children who share their burdens. And we must march with the formerly incarcerated as they resist the slow death of hunger and cold.

The story of mass incarceration in America is bigger than American jails and prisons, even with their two million captives. And its bigger than probation and parole, even with the five million people held in the prison of their homes through ankle bracelets, weekly drug tests, and GPS technology. This is because mass incarceration has an afterlife, and that afterlife is a supervised societya hidden social world and an alternate legal reality. The prison lives on through the people whove been convicted long after they complete their sentences, and it lives on through the grandmothers, lovers, and children forced to share their burdens because they are never really allowed to pay their so-called debt to society.