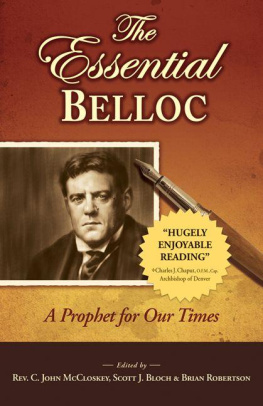

The

Essential

B ELLOC

A P ROPHET FOR OUR T IMES

The

Essential

B ELLOC

A P ROPHET FOR OUR T IMES

Collected by THE REV. C. JOHN MC CLOSKEY,

SCOTT J. BLOCH, AND BRIAN ROBERTSON

2010 Rev. C. John McCloskey, Scott J. Bloch, and Brian Robertson

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical reviews, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-935302-84-1

ISBN: 193-530-2-841

Cover art and design by Christopher J. Pelicano

Printed and Bound in the United States of America

Saint Benedict Press, LLC

Charlotte, North Carolina

2010

This book is dedicated to our families, our wives and children.

Contents

What Anglo-Saxons Call a Foreword, But Gentlemen a Preface

James V Schall, S.J

Introduction

Scott J Bloch

Acknowledgments

T he editors of this book would like to thank the following individuals who contributed to this book through research and editing: Donato Infante, Peter Hilaire Bloch, Mary Catherine Bloch, Prof. David Whalen, Alan Hicks, Father James Schall, William Saunders, and members of the Hilaire Belloc Society. We would like especially to thank Robert Royal and the Faith and Reason Institute for supporting this venture and making it possible. And last but not least, to Todd Aglialoro of Saint Benedict Press for believing in this book and seeing it through.

On Caring Too Much: The Charm of Belloc

B ut I noticed only this morning, turning over one of her pages, a charming and comforting reflection. She says of one of the men in her books that one of the women in her books who came across him paid no attention to what a certain gentleman thought of any matter because she did not care enough about himnot in the sense of affection but in the sense of attention. So speaks this ambassadress from her own sex to mine, and I will not be so ungenerous as to leave her without a corresponding reply.

My dear Jane Austen, we also do not care a dump what any woman thinks about our actions or our thoughts or our manners unless they have inspired us towhat shall I call it? It need not be affection, but at any rate attraction, or, at least, attention. Once that link is established, we care enormously: indeed, I am afraid, too much.

Hilaire Belloc, Jane Austen, 1941.1

The subject of this preface is the charm of Belloc. The phrase is redolent of Plato. Platos Republic was written to counteract the charm of Homer on the Greeks. Plato knew that no mere philosopher could ever command the attention that a poet could command. His recourse was to combine poetry and philosophy into one single book, the Republic itself, whose charm we all know, or if we do not, we do not belong to the civilization that I address here. Plato sought to out-charm Homer.

Do I think Belloc was another Plato? What I do think is that he had to do substantially the same thing. For the false ideas about the gods a true idea had to be found and made loveable. Few would read proofs for the existence of God and understand them. But they might order their souls correctly if they sang, if they heartily sang, the music of the real gods. Belloc sang a lot. His writing is charming. Beware of him, for his charm has sparks of the same allure of Plato, though in the service perhaps of a different God, or better, of one who, by the time of Belloc, had let us know who He was.

Thus, Belloc could sing in the Four Men: And thank the Lord / For the temporal sword, / And howling heretics too; / And whatever good things / Our Christendom brings, / But especially barley brew!2 Revelation is about thanking the Lord, about the things of Caesar, about the heretics who deny Trinity and Incarnation, and those who tell us that the good things of this earth are evil, even when they are good. We thank God for beer and wine, as Chesterton I believe said, by not drinking too much of them. Aristotle said this also; such is the sanity of both.

To introduce anyone who has the happy fortune to read such a book as The Essential Hilaire Belloc is to introduce him to the whole world, to what happened in it, and to what lies beyond it. But in so reading this book, we memorably pass through the world itself, through its towns, rivers, inns, and cities, through the homes of men, to where they fought each other, where they loved, where they argued late into the night about what is.

Often the passage is on foot, or in a boat, or sometimes it consists in just sitting quietly at the George, the inn at Robertsbridge, drinking that port of theirs and staring at the fire. Here, in the minds eye, there arises a vision of the woods of home and of another placethe lake where the [river] Arun rises.3 Belloc was a wanderer who loved to be at home: two virtues kept together only with the greatest of delicacy, but both belong to our being in this world.

The purpose of Hilaire Belloc, I mean that of his existence in this world, is to be sure that what is solid, the permanent things, do not pass us by, even when they are not of our time or of our place, embedded as they usually are in the most ephemeral of things, among which things we ourselves stand outside of nothingness. Belloc teaches us that, unless we set down in print, yea in print, the places we know, the people we love, the things that amuse us, they will disappear, even in our efforts to remember them. As a man will paint with a peculiar passion a face which he is only permitted to see for a little time, so will one passionately set down ones own horizon and ones fields, before they are forgotten and have become a different place. Therefore it is that I have put down in writing what happened to me now so many years ago.4

We are given our own lives to live and we must live them in our time and place. We have friends, but, as Aristotle said, we cannot be friends with everyone at the risk of having no friends at all. But one life is not enough. We must live other lives. We can best do this more living, I think, by following Belloc in what he called the towns of destiny, in the history of England and France, along the path to Rome, yea, even into the servile state and the characters of the Reformation.

Belloc was a man of England, a man of France, a man of Europe, yes, a man of the world. He was, I think, the best short essayist in the English language. How often have I thought of Bellocs sailing out of the port of Lynn, So having come round to the Ouse again, and to the edge of the Fens at Lynn, I went off at random whither next it pleased me to go. Where it pleased Belloc to go at random is always a place worth seeing, a place we could not now see without him.

And what had Belloc seen in Lynn? For these ancient places do not change, they permit themselves to stand apart and to reposeby paying that pricealmost alone of all things in England they preserve some historic continuity, and satisfy the memories in ones blood.5 What a remarkable expression that is, to satisfy the memories of ones blood. Our memories, to be ours, must be more than those memories we have only of ourselves. Our blood remembers our grandparents, our ancestors, the kind of being we are whose soul and body mysteriously belong both to eternity and to our forefathers who begot us.