Copyright 2015 Joseph Pearce

All rights reserved. With the exception of short excerpts used in articles and critical review, no part of this work may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in any form whatsoever, printed or electronic, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

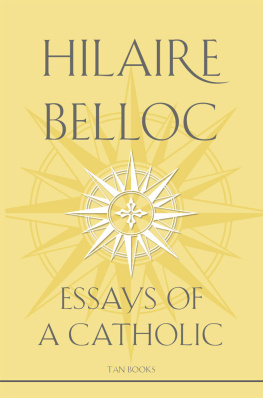

This book was first published in the United States by Ignatius Press in 2003. This TAN Books edition has been re-typeset and revised. Revisions include occasional spelling, punctuation, and typography corrections.

Typeset by Lapiz

Cover design by Caroline Kiser

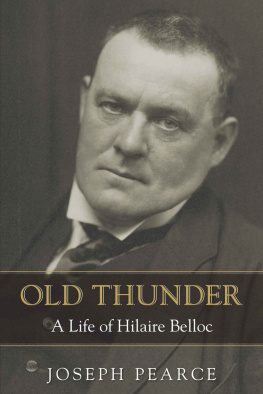

Cover image: British historian and author Hilaire Belloc. Photo by Time Life Pictures/Mansell.

ISBN: 978-1-61890-656-4

Published in the United States by

TAN Books

PO Box 410487

Charlotte, NC 28241

www.TANBooks.com

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For James Catford,

In lasting gratitude for the faith he has always shown in my work

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been truly blessed during my work on this volume to have received the help and cooperation of several of Bellocs descendents. I enjoyed many delightful hours in the presence of his granddaughter, Sister Emmanuel Mary, nee Marianne Jebb, amidst the idyllic tranquility of the convent of the Canonesses of St. Augustine, the order she joined in 1945. A similarly fruitful visit was enjoyed in the company of Rom Philip Jebb, Bellocs grandson, at Downside Abbey, and with Zita Caldecott, another granddaughter, in her London flat, nestled in the shadow of Westminster Cathedral. The Earl of Iddesleigh and Edward Northcote, grandsons of Marie Belloc Lowndes, offered their time and their anecdotal memories. Barbara Wall and Bob Copper were also kind enough to share their memories with me. Chloe Blackburn, daughter of the artist Sir James Gunn, shared her fond reminiscences of her fathers friendship with Belloc and Chesterton. I am particularly indebted to Zita Caldecott, Chloe Blackburn, and Miranda Mackintosh for the loan of many letters to and from Belloc, the quotations from which have enriched this volume considerably.

Apart from the unique insights offered by the aforementioned, my work has been assisted greatly by those academics and devotees of Belloc who have assisted me in my research. Kim Leslie, chief archivist at the West Sussex Record Office in Chichester, was utterly selfless in making many previously unpublished letters available to me, as were Grahame and Gill Clough at the Belloc Study Centre, also in Sussex. Mike Hennessy allowed me access to his own exhaustive research into Bellocs parliamentary career, and I am grateful to William Griffiths and Alan Davidson for their knowledge and their support. Gerard Tracey, Archivist at the Birmingham Oratory, was very helpful in assisting my efforts to piece together the missing details of Bellocs schooldays at the Oratory school.

Further afield, I have been the beneficiary of the fruits of the diligent labour of a number of American academics. Dale Ahlquist spent several hours trawling through the Special Collections in the OShaugnessy-Frey Library at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota. During his endeavors on my behalf he was assisted by Jim Kellen, the Librarian responsible for the Special Collections. Nicholas Scheetz, Manuscripts Librarian at Georgetown University Library, was generous with his time and his patience as he guided me through the Belloc material at Georgetown. Marty Barringer, Associate University Librarian, responsible for the Special Collections and Archives at Georgetown, was also very helpful, as was my friend and colleague on the Saint Austin Review, Father James V. Schall.

By far the greatest collection of Belloc material is to be found at Boston College, and I have to thank several people for their valuable assistance. Robert K. ONeill, Father Frank Vye, John Atteberry and, most particularly, Peter Kreeft were all most helpful in making the material at Boston College available to me.

Others who have assisted in sundry ways include Father Fessio at the Ignatius Press and Amy Boucher-Pye at HarperCollins. Penultimately, and emphatically, I must thank my wife, Susannah, who assisted me in multifarious ways throughout the months in which this labor of love was in preparation. Ultimately, however, I must conclude with a confession of all the sins of omission that I have doubtless committed in leaving out many other people who have assisted my efforts on this volume. To these unsung heroes and heroines I offer my sincerest gratitude and my heartfelt apologies for my failure to acknowledge their efforts individually.

Preface

By Dale Ahlquist

G.K. Chesterton said that he and Belloc were completely different. It just so happened that they agreed on politics and religion. It was precisely that agreement that has caused most observers to associate them with one another. Certainly they both advocated widespread ownership and local-based economies. They both defended the Catholic faitheven before Chesterton became Catholic. They both extolled laughter and the love of friends. And they were both virtuosos of the written word, which was not only put to use defending the same ideas, but defending each other. It was, of course, their agreement on politics and religion that provoked George Bernard Shaw to label them as one four-legged beast known as the Chesterbelloc.

But they were different.

The revival of interest in Chesterton has predictably helped revive an interest in Belloc as well, but it is almost as if Belloc has been forced to tag along, as if being attached to Chesterton by a tether. I am often asked, When are you going to do Belloc? as if I am expected to do what I have been involved in doing with Chesterton: establishing a literary society devoted to him, collecting and cataloguing his entire literary output, drawing attention to his writings through a magazine, a television show, an active website, an annual conference, dozens of local societies, and putting a great deal of effort into reinvigorating scholarship and research. But I still have my hands full. Someone else is going to have to do Belloc. After all, they were different. And it should be done. Belloc deserves it. He is a great writer and a great warrior and certainly a great wit, especially when it comes to the skewering in verse of naughty boys and girls.

Joseph Pearce, of course, does not have the same limitations I have. While I am eternally stuck on my one writer, he simply takes on one great literary figure after another and writes a profound and permanent treatment of their life and works, managing somehow to distill a great mass of material into one book, even while adding to our understanding and pointing out something new. But even after Joseph Pearce began his prolific career as a biographer, starting with his book on Chesterton, the question among his growing legion of fans was When will he do Belloc? The assumption was: if one, then the other.

But they were different. And this, the most expected of Joseph Pearces books, bears out the unexpected conclusion.

In some ways, both Chesterton and Belloc have been treated unfairly because of the obligation to hook them together. What some critics do not like about Chesterton (i.e. his politics and his religion), they blame on Belloc. What some critics admire about Belloc (something other than his politics and religion), they attribute to Chesterton. Wrong on all counts. Neither can escape the others shadow (and as good friends, neither would wish to), but Belloc has suffered most from being part of the mythological creature because his work is seldom considered independently of Chesterton.

But they were different.

Next page