Robert Zaretsky - The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas

Here you can read online Robert Zaretsky - The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: University of Chicago Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

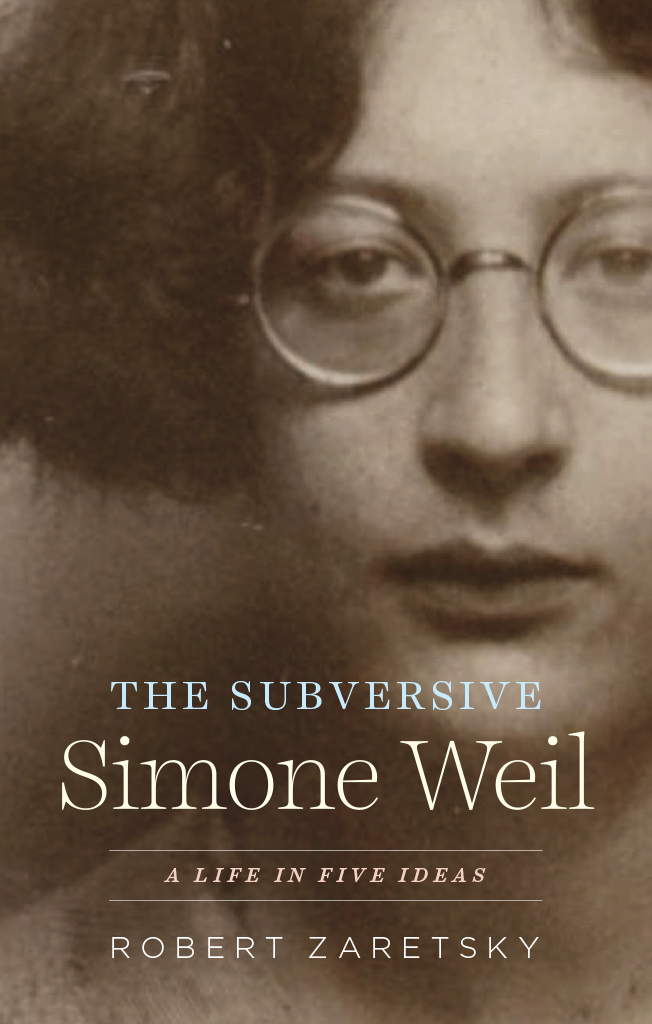

- Book:The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Chicago Press

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Robert Zaretsky

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2021 by Robert Zaretsky

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54933-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-54947-7 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226549477.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zaretsky, Robert, 1955 author.

Title: The subversive Simone Weil : a life in five ideas / Robert Zaretsky.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020038852 | ISBN 9780226549330 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226549477 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Weil, Simone, 19091943. | Women philosophersFranceBiography. | Philosophy, French20th century.

Classification: LCC B2430.W474 Z38 2021 | DDC 194dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038852

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Louisa

Three months ago, I sent the final manuscript for this book to my editors at the University of Chicago Press. Under the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, the world I knew then now seems as ancient as the Greece that Simone Weil so deeply loved. So many of the habits and happenings, occupations and preoccupations I thought were fixed forever have faded or already fled.

By the time this book is in your possibly gloved hands, these very words may seem no less ancient. The world is changing at a pace that would stun even Heraclitus. Insisting that change defined our world, Heraclitus concluded that we cannot step into the same river twice. Yet the novel coronavirus has taught us a newer truth: we cannot step into the same river even once.

Like everyone else, I am trying to keep my head, and the heads of those near and dear to me, above the white water of history. Nevertheless, in our breathtakingly changing world, a world we now divide between essential and nonessential goods, I know the writings of Simone Weil will always fall in the former category. Force and freedom, affliction and attention, community and care are more than ever ideas for our age of microbiological and ideological plagues.

These ideas led to at least one key ideal for Weil. In one of her last works, The Need for Roots, she wrote: There exists an obligation towards every human being for the sole reason that he or she is a human being, without any other condition requiring to be fulfilled, and even without any recognition of such obligation on the part of the individual concerned. Few claims are more crucial for both my time and your time. And time alone will tell whether we are capable of fulfilling it.

Houston

April 21, 2020

How much time do you devote each day to thinking?

Simone Weil

More than three-quarters of a century ago, on August 26, 1943, the coroner at Grosvenor Sanatorium, a sprawling Victorian pile located in the town of Ashford, about sixty miles southeast of London, ended his examination of a patient who had died two days earlier. The cause of death, he wrote, was cardiac failure due to myocardial degeneration of heart muscles due to starvation and pulmonary tuberculosis. But the clinical assessment then gives way to what appears to be an ethical judgment: The deceased did kill and slay herself by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed.

The deceased was buried in a local cemetery; a flat marker laid across her grave was engraved with her name and relevant dates:

Simone Weil

FVRIER 1909 AOT 1943

Weils grave, its location highlighted on the cemetery map, has since become one of Ashfords most visited tourist sites. By way of acknowledging the constant stream of visitors, a second marble slab explains that Weil had joined the Provisional French government in London and that her writings have established her as one of the foremost modern philosophers.

One can fit only so much on a grave marker. This is especially the case with Simone Weil. It has become a ritual among Weil biographers to sum up her life with a series of contradictions. An anarchist who espoused conservative ideals, a pacifist who fought in the Spanish Civil War, a saint who refused baptism, a mystic who was a labor militant, a French Jew who was buried in the Catholic section of an English cemetery, a teacher who dismissed the importance of solving a problem, the most willful of individuals who advocated the extinction of the self: here are but a few of the paradoxes Weil embodied. It helps to see these instances less as inconsistencies in Weils work and lifethough, at times, they are precisely thisthan as invitations to reflect on both one and the other. In her notebooks, she wrote that the proper method of philosophy consists in clearly conceiving the insoluble problems in all their insolubility and then in simply contemplating them, fixedly and tirelessly, year after year, without any hope, patiently waiting.

By this measure, Weil concluded, there are few philosophers. And one can hardly even say a few. In turn, we cannot stand for very long in her severe company without feeling deeply discomforted. This is as it should be. To a degree rare in the modern ageor, indeed, any ageSimone Weil fully inhabited her philosophy.

To echo the fictitious coroners report on the death of the Jesuit priest in Albert Camuss novel The Plague, Weils end remains a questionable case. For Weil, death was neither the means nor the end to philosophy. Instead, it was a possible consequence of doing philosophyat least if we understand philosophy not as an academic discipline, but as a way of life. As the contemporary philosopher Costica Bradatan has observed, Philosophizing is not about thinking, speaking or about writing... but about something else: putting your body on the line.

As with Socrates and Seneca, Benedict Spinoza and Jan Patocka, Weil obliges us to recall not just the price of the philosophical life, but its purpose. Few of us, I know, can ask this of ourselves. As Stanley Cavell wrote, Weil was exceptional in her refusal to be deflected from the reality of life. And yet this inability to be deflected is a gift, or curse, that most of us would gladly refuse. This is how it isperhaps even as it should be.

This book explores five core concepts in Weils thought. While I detail several episodes in Weils life, I do not treat chronology as consistently as the historian in me would have liked. And so, allow me to trace in the next few pages the arc of her life.

Born in Paris in 1909, five years before the outbreak of World War I, Weil was the child of Bernard and Salomea (Selma) Weil. The well-to-do parents were fiercely nonobservant Jews who prized the citys cultural and literary life. Born in Russia to a prosperous family of merchants, Salomea Reinherzwho shortened her first name to Selmaleft for Belgium, then France with her parents following a rash of pogroms in 1882. Her family bristled with poets and musicians, and Selma was herself an accomplished pianist and singer. Bernard Weil was the child of a successful business family from Strasbourg that chose French citizenship when Germany annexed Alsace at the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. Though his parents were practicing Jews, Bernard gravitated to anarchism and atheism as a young man. Although he never surrendered his atheism, he did put aside his anarchist sympathies upon becoming a successful doctor. One year after the couples marriage in 1905, their son Andr was born; three years later, Si-mone followed. Shortly after his daughters birth, Bernard moved his family into an imposing apartment on the chic Boulevard Saint Michel, where he and Selma provided their children with love and attention, as well as the aspirations and advantages expected of the haute bourgeoisie in Belle poque France.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas»

Look at similar books to The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.