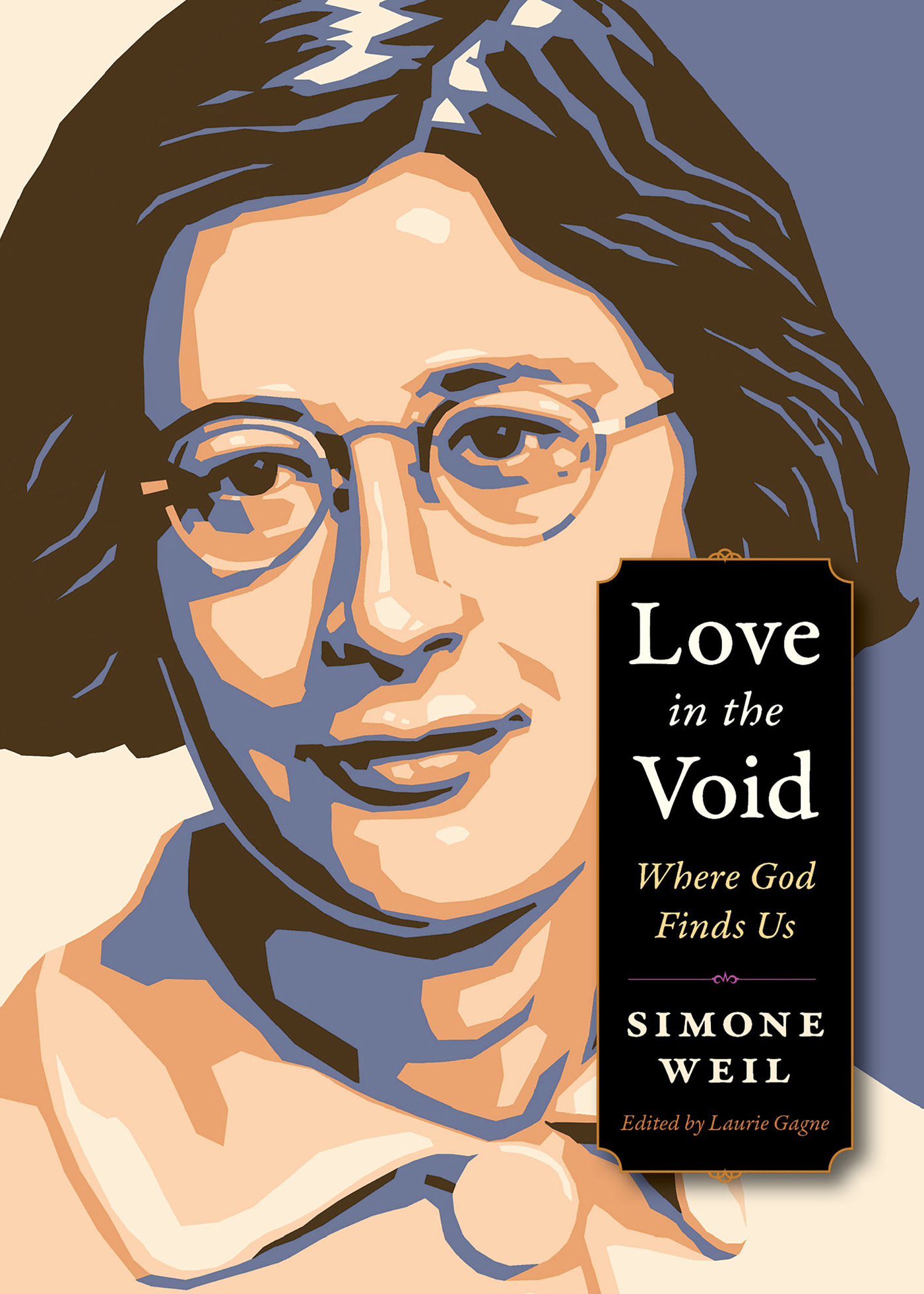

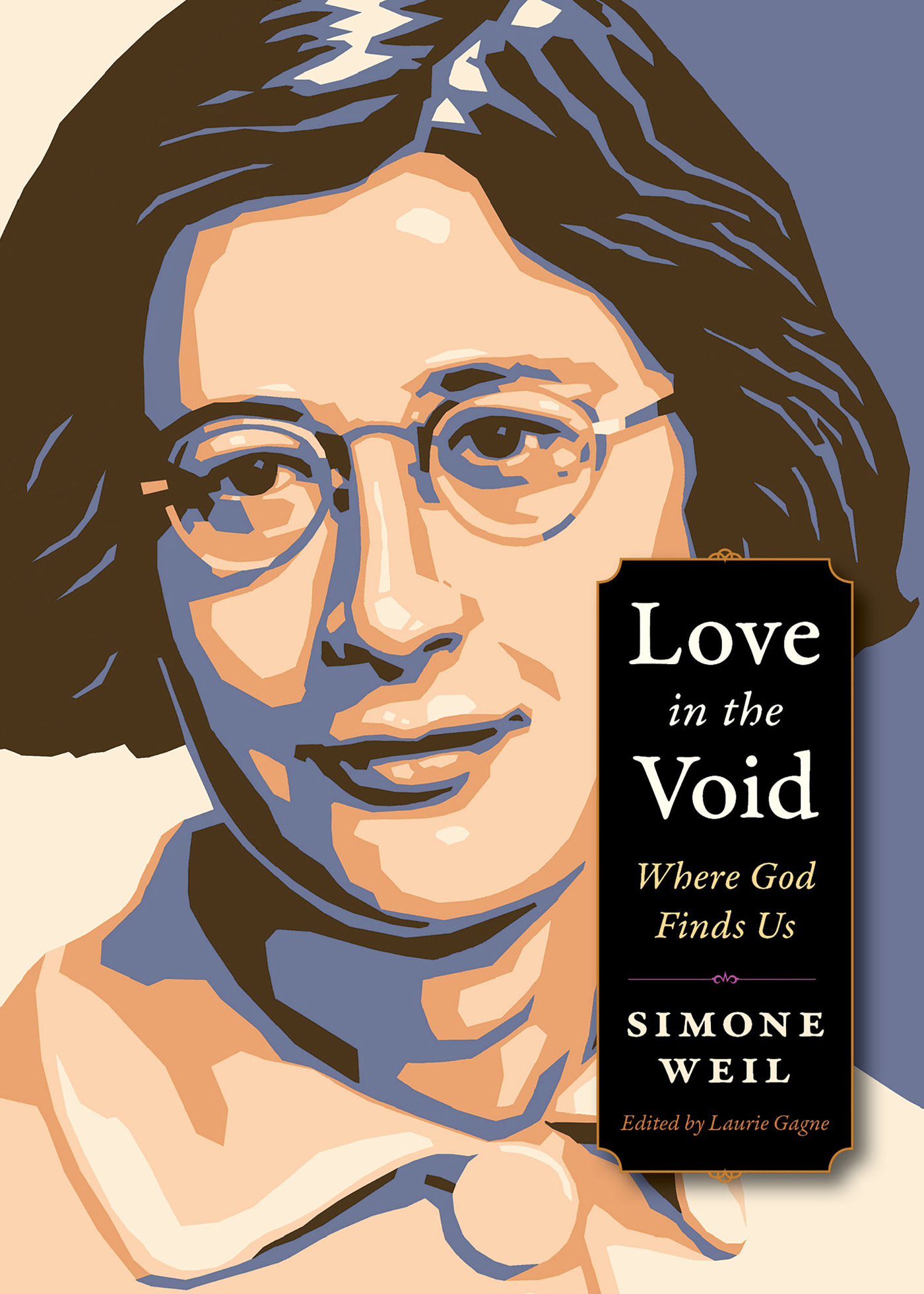

Love in the Void

Love in the Void

Where God Finds Us

Simone Weil

Edited by Laurie Gagne

PLOUGH PUBLISHING HOUSE

Published by Plough Publishing House

Walden, New York

Robertsbridge, England

Elsmore, Australia

www.plough.com

Copyright 2018 by Plough Publishing House

All rights reserved.

PRINT ISBN: 9780874868302

EPUB ISBN: 9780874868319

MOBI ISBN: 9780874868326

PDF ISBN: 9780874868333

Cover art copyright 2018 by Julie Lonneman. Photograph on page ii from Alamy Stock Photo. Excerpts from Gravity and Grace by Simone Weil, translated by Arthur Wills, copyright 1947 by Librairie Plon; translation copyright 1952, renewed 1980 by G. P. Putnams Sons. Used by permission of G. P. Putnams Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, and by Routledge (Taylor & Francis Group) for the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. All rights reserved. Excerpts from Waiting for God by Simone Weil, translated by Emma Craufurd, translation copyright 1951, renewed 1979 by G. P. Putnams Sons. Used by permission of G. P. Putnams Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Contents

Introduction

THE WRITINGS of philosopher and mystic Simone Weil first appeared in the late 1940s and early 1950sthe period after World War II characterized by a widespread desire to return to normalcy in Western societies. Having defeated the great beast of totalitarianism, the liberal democracies concentrated on creating the good life at home. In America, especially, it was the golden age of the middle class: a comfortable, even affluent lifestyle seemed within the reach of everyone. Given this context, it is not surprising that Weil, who had died in 1943, quickly achieved legendary status among a whole generation of countercultural intellectuals and spiritual seekers. Her writings are radically, vehemently anti-bourgeois, as was her short, intense life. Christians and atheists alike seemed to find in Weil a corrective to the burgeoning consumer culture that threatened to stifle the life of the mind and the soul. The French philosopher

In our time, too, when religionreally, fundamentalist religionhas once again emerged as a force in world events, Simone Weils writings have again been invoked, this time to distinguish between true religion and false religion or idolatry. In Gravity and Grace, Weil uses the language of idolatry to describe the way that religion can become destructive. There, we read that idolatry comes from the fact that, while thirsting for absolute good, we do not possess the power of supernatural attention, and we have not the patience to allow it to develop.

Never dreaming that she would be the subject of all this attention so many decades later, Simone Weil died in 1943 at the age of thirty-four, the time of life when most young people are hitting their stride in work and relationships. Commitments have been made, sometimes vows have been taken, and theres often a mortgage to cement the young persons ties to a particular place and way of being for the next fifty years. Even today, when people travel the globe and change jobs frequently, maturity still means some measure of settling down. In the brief time that she had on this earth, Simone Weil constructed a life that was antithetical to time-honored standards of worldly success. She sought to uproot herself from everythingher parents solicitousness, the comfortable surroundings of her childhood, and even the normal benchmarks of academic achievementto which she might form an attachment. Her goal was an untrammeled heartthe necessary condition, she believed, for knowing the truth. We can chart her life according to the turning points in this passionate quest. The body of work she left usvirtually all of it published posthumouslyis the fruit of an anguished, but ultimately luminous spiritual journey.

Born in 1909 to a Jewish family in Paris, Simone Weil had a privileged, extremely intellectual childhood. She and her older brother, Andr, who was widely regarded as a prodigy (he became an internationally recognized mathematician) would memorize long passages from the classics of French drama and play complicated math games; this before she even went to school. At the Lyce Henri IV, under the tutelage of the well-respected but non-conformist philosopher mile-Auguste Chartier, her intellectual vocation seemed confirmed. He judged her short essays outstanding and predicted a brilliant career for the high-minded young woman. However, at the age of fourteen, she went through a deep depression during which she even thought of dying, convinced, as she writes in her spiritual autobiography, of the mediocrity of her natural faculties. The comparison with

This insight, that truth (which included, for her, beauty, virtue, and every kind of goodness

Impulses such as she was describing are not a matter of following the egos desires, however insistent. Instead, they spring from the point of transcendence in usthe soulwhich tends unerringly toward eternal truth. Trusting this tendency, instead of more rational considerations, resulted in a decidedly unspectacular teaching career for Weil. After graduating highest in her class from the prestigious cole Normale Suprieure, she taught at girls schools in the French countryside from 1931 to 1938. A lightning rod for controversy because of her extreme opinions, she became embroiled in conflicts with school boards, who strongly objected to the social activism she could not resist undertaking.

Ever since the age of five, when she had refused to eat sugar, having heard that it was denied the soldiers at the front, Weil had exhibited a desire to identify with those who suffer. (Simone de Beauvoir, a classmate of Weils at university, says that when she heard that Weil had burst into tears on hearing about a famine in China, she envied her for having a heart that could beat right across the world.) In Le Puy and Auxerre, Weils first two teaching assignments, she took up the cause of the workers, writing articles for leftist journals, marching and picketing, donating most of her salary to the purchase of books to be used in workers study circles, and providing free lessons to all comers. Reportedly, her students at both schools loved her, but in each place, Weil was dismissed after only one year.

A break from teaching gave Simone Weil the opportunity to be one with the workers quite literally. She obtained employment at a succession of factories in Paris, including the Renault automobile plant. Proposing to study the conditions of industrial work, she immersed

Paradoxically, Weil derived tremendous spiritual benefit from her time in the factory. Her new consciousness, she says, turned her in the direction of Christianity. Prior to her factory experience, Weil had believed that we progress toward truth or the good through our own effortsby obeying the hearts impulses, as we have noted, and by focusing all our energies on the good we desire. Her awareness of powerlessness in the face of death, however, made her realize that at a certain point on the spiritual journey all we can do is wait. By accepting death and powerlessness, without denying the hearts longing, we position ourselves to receive the good. Christianity teaches that the good comes to us.

Weil would begin to learn this firsthand. She went to Portugal with her parents to recover from the shattering experience of factory work. One night, in a little fishing village, she observed a procession of fishermens wives making a candlelit tour of all the ships, singing ancient hymns of a heart-rending sadness. Touched to the core of her own heart, she came to an insight: Christianity is pre-eminently the religion of slaves, she thought; slaves cannot help belonging to it, and I among others.

Next page