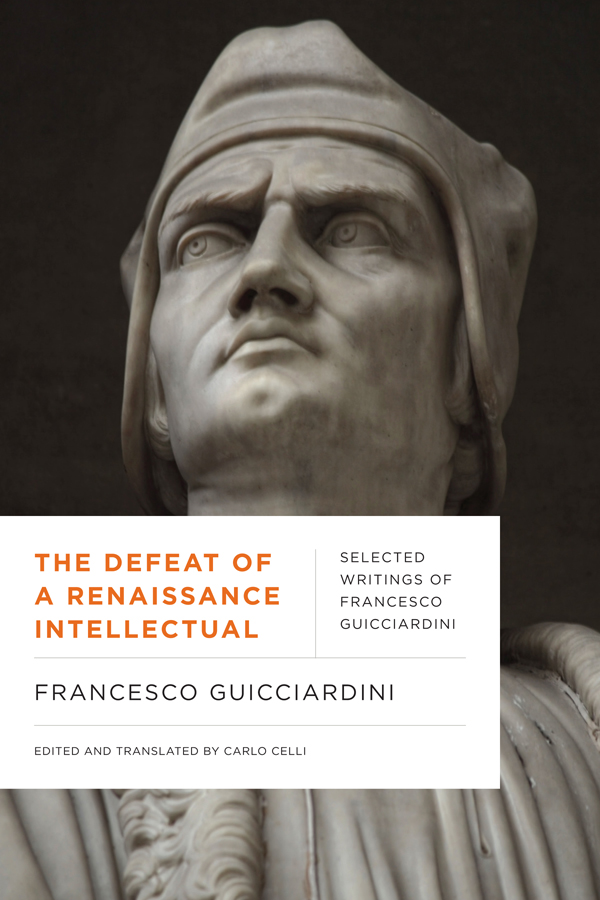

The Defeat of a Renaissance Intellectual

Habent sua fata libelli

Habent sua fata libelli

EARLY MODERN STUDIES SERIES

GENERAL EDITOR

Michael Wolfe

Queens College, CUNY

EDITORIAL BOARD OF EARLY MODERN STUDIES

Elaine Beilin

Framingham State University

Christopher Celenza

Johns Hopkins University

Barbara B. Diefendorf

Boston University

Paula Findlen

Stanford University

Scott H. Hendrix

Princeton Theological Seminary

Jane Campbell Hutchison

University of WisconsinMadison

Mary B. McKinley

University of Virginia

Raymond A. Mentzer

University of Iowa

Robert V. Schnucker

Truman State University (Emeritus)

Nicholas Terpstra

University of Toronto

Margo Todd

University of Pennsylvania

James Tracy

University of Minnesota

Merry Wiesner-Hanks

University of WisconsinMilwaukee

The Defeat of a Renaissance Intellectual

Selected Writings of Francesco Guicciardini

By Francesco Guicciardini

Edited and Translated by Carlo Celli

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Guicciardini, Francesco, 14831540, author. | Celli, Carlo, 1963 editor, translator.

Title: The defeat of a Renaissance intellectual : selected writings of Francesco Guicciardini / by Francesco Guicciardini ; edited and translated by Carlo Celli.

Other titles: Early modern studies series.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2019] | Series: Early modern studies series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: A collection of writings by papal advisor and historian Francesco Guicciardini (14831540), including letters, treatises, reports, and orations spanning his long career in service to the MediciProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019004846 | ISBN 9780271083483 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: ItalyHistory14921559. | ItalyPolitics and government12681559. | Florence (Italy)History14211737. | Florence (Italy)Politics and government14211737. | Papal StatesHistory14171605. | Medici, House of. | Guicciardini, Francesco, 14831540.

Classification: LCC DG738.14.G9 A25 2019 | DDC 945/.06dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019004846

Copyright 2019 Carlo Celli

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z39.481992.

CONTENTS

For generous and kind assistance with the present volume, I thank the following from Bowling Green State University: the interlibrary loan office, Sherri Long, Linda Brown, the staff at the Office of Sponsored Research, the staff at the Department of World Languages and Cultures; the editors and staff at Truman State University Press and Penn State University Press; Sara Piccolo, and Marga Cottino-Jones.

The Italian Renaissance was a period of cultural and artistic rebirth, a rediscovery of classical culture that brought epochal creativity to science, commerce, and the arts, with the city of Florence as a cradle of achievement. However, between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, Italy and Europe suffered periods of economic depression and societal chaos stemming not solely from cataclysms like the 1348 Black Death but also from continuous wars, religious turmoil, famine, and increasing authoritarian interference into political and economic life. In this climate, the ascendant national monarchies in France, Spain, and England, and regional corollaries such as the Medici family of Florence, affirmed dominance over oligarchical and republican civic institutions.

Renowned intellectuals of the period wrote treatises, histories, letters, and poems rationalizing authoritarian rule and the consequent suppression of economic and political liberty. In political and social terms, these writers behaved as establishment intellectuals, harnessing their talents to further the power of hegemony, in this case of monarchical rule. Dante Alighieri (12651321) brilliantly decried the moral failings of his generation and resulting political strife in the Divine Comedy. However, Dante also championed the political cause of Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of Luxemburg (1269/741313), penning De monarchia (On Monarchy), a treatise providing intellectual cover for temporal rule over Italian communes and cities by a German Holy Roman emperor. Dantes political stance would have meant the descent of German troops into Italy, a contingency inhabitants of the peninsula have historically sought to avoid. Francesco Petrarca (13041374) penned a famous poem inciting Italian princes and republics to renew ancient Roman military policy, My Italy (Canzoniere, CXXVIII). However, he also wrote a fawning letter (Senili, XIV, 1) to Francesco da Carrara, overlord of Padua, on the duties of a prince in the tradition of humanists seeking patronage from local despots. Niccol Machiavelli (14691527) may have had a firm foundation in republican ideology and practice. However, once the Florentine Republic where he worked fell to a Medici coup supported by Spanish troops in 1512, he penned The Prince (1513), promoting himself to Florences Medici rulers, advising them to mask ruthless extremism with piety to maintain power. Similarly, Baldassare Castigliones (14781529) The Book of the Courtier (1528) advises individuals to strive for personal promotion as nonchalant gentlemen adept at currying favor with a ruling lord. These writers adapted to and wrote for the power establishment of their day, which was increasingly autocratic.

During the lifetime of Francesco Guicciardini (14831540), Florentine politics were dominated by the struggle of republican leaders to retain civic political autonomy against the ambitions of the Medici family. Competition for power between popular, aristocratic, and monarchical factions had characterized Florentine politics since the late Middle Ages but took an authoritarian turn with the rise of the Medici family from a financial to a political power. The Florentine Republic became a de facto Medici principality during and following the rule of the Medici clan patriarch, Cosimo de Medici (13891464). The geopolitical context during Guicciardinis lifetime was the Italian Wars (14941559), when Italy was a battlefield in the contest for continental hegemony between the Habsburg monarchs of Spain and Austria and the Valois of France, beginning with the invasion by the French king Charles VIII (14701498) in 1494 and ending with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrsis in 1559, when the French relinquished claims in Italy.

Guicciardini spent his professional life as representative, functionary, and apologist for the Medici clan, serving a long list of Medici lords over his career. He advised Lorenzo di Piero de Medici (14921519) and Giuliano di Lorenzo de Medici (14791516), the first Medici lords of Florence following the 1512 fall of the Florentine Republic and the subject of Guicciardinis treatise How to Ensure the State for the House of Medici. He was counsel to Giovanni di Lorenzo de Medici (14751521), who ruled as Pope Leo X from 1513 to his death in 1521 and appointed Guicciardini governor of Romagna. Guicciardini was lieutenant general and advisor to Giulio di Giuliano de Medici (14781534), who ruled as Pope Clement VII from 1523 to his death in 1534. Guicciardini aided the accession to the duchy of Alessandro de Medici (15101537), the alleged illegitimate son of Lorenzo di Piero de Medici (14921519) or the future Clement VII. Guicciardini encountered other Medici who opposed Alessandros ascension to the duchy of Florence, such as Ippolito de Medici (15091535) and Alessandros eventual murderer, Lorenzino de Medici (15141548), also known as Lorenzaccio. Guicciardini was eventually removed from the Medici administration by Cosimo I (15191574), who succeeded Alessandro.

Habent sua fata libelli

Habent sua fata libelli