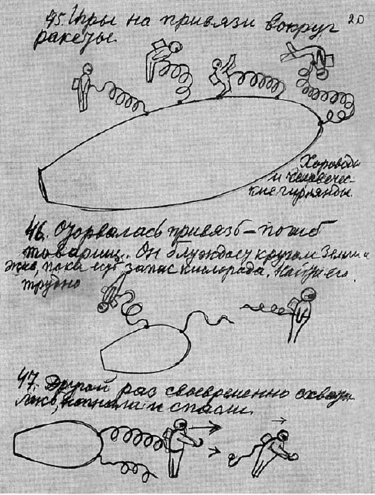

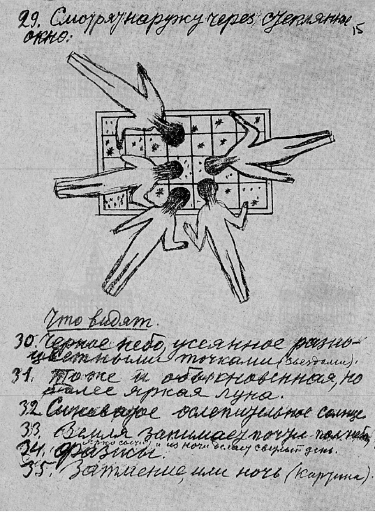

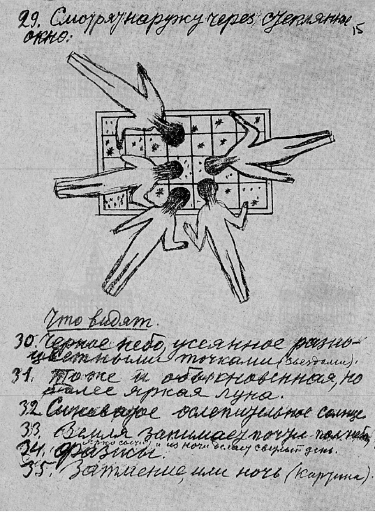

), explains that life in space involves playing games around the spaceship, and forming human garlands. In the two sketches beneath the garland, play is replaced by celestial drama. The hose connecting one cosmonaut breaks and his body drifts away from the ship. He is dead, the note explains. But in the third scene, an arrow points from the eyes and hands of a tethered cosmonaut toward the one floating in space. In an alternative scenario, the explanation tells us, a fellow cosmonaut reacts in a timely manner to the mishap and manages to save his comrade.

The other source of his self-education was the work of Jules Verne. Relying on textbooks and Verne, this visionary created a mathematical model of liquid-propelled rockets, without which the Soviet space programme of the 1960s would have been impossible. Tsiolkovsky, a scientific amateur by common standards, operated from a homemade lab, and during the tsarist era supported himself by writing popular science for members of amateur space travel societies. During the Stalinist period, several years before his death, he finally received official recognition as a national hero.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, sketch no. 29 from Album of Cosmic Journeys made for the film The Cosmic Voyage, 1932.

Since the transcendental power in the world is still irrational, Tsiolkovsky writes,

But humankind evolves together with the cosmic will, toward greater perfection, toward self-empowerment, toward a glorious state.

In 1928, the year The Will of the Universe was published, the era of Stalin's Five-Year Plans began. In this context, Tsiolkovsky's reasoning about the nature of human progress and the celestial destination of the human race fits into the communist master narrative. It matches the teaching that first there is socialism, an evolutionary stage on the path toward the end of history, and communism is this history's end, a perfect classless and stateless society in which the imperfections of the human race and the mixture of sensible and stupid, kind and cruel will finally vanish. Tsiolkovsky's work on situating communism in outer space and presenting the path toward life in it as the manifestation of a cosmic will in many ways lends the communist master-narrative a transcendental dimension, and presents the course of Soviet history as part of cosmic evolution.

Tsiolkovsky's celestial utopia is situated in outer space the metaphysical milieu of the cosmic void. To picture this void, to invent the means for reaching it, means not only to design an alternative reality, but also to speculate about the ends of human existence and the meaning of history. What does this mean in the context of socialist speculation? What form does a celestial utopia take when a religious interpretation of the heavens is replaced with a socialist one? How did projects such as Tsiolkovsky's, or, as later chapters explore, projects which pair the realistic with the fantastic, the far-reaching vision with the ridiculous, articulate the metaphysics of communism? How do the instigators of such projects speak about history or about the ends of communism as the radical modernist effort to transform the world? A good way to begin considering answers to these questions is to look precisely at the tradition of cosmic and celestial utopias the most literal version of communist metaphysics from their origins in pre-Revolutionary science and fiction and up to their concluding chapter at the end of Soviet history.

Communism and the Martians

, Muravev believed that the rhythm of factory work has to be synchronized with that of the cosmos; at that point the proletariat will eliminate the earthly notion of time and begin to live in the celestial eternal present.

The most popular pre-Revolutionary book that presents revolutionary life as celestial life is Alexander Bogdanov's Red Star, published in 1908. Bogdanov, one of the founders of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party from which the Bolsheviks and the Soviet Communist Party descended, decided to popularize the proletarian struggle. So he wrote an adventure story in which the protagonist travels to the ideal communist society in space. Martians, led by an undercover agent named Menni, select the hero of the story, Leonid, a member of the Russian Socialist Democratic Party, to visit Mars so he can report back to the humans about what he learns. He travels via an etheroneph powered by antimatter and observes daily life on the Red Planet. He sees factories in which workers indulge in fulfilling labour and are free to change professions; fantastic glass-clad domestic architecture; progressive ways of childrearing; free love; and art museums transformed from sites for collection and accumulation into places for study. By experiencing everyday life in a Martian society, Leonid gets a picture of what his political struggle on Earth will bring about.

In one scene in the novel, Leonid admires the beauty of vegetation on Mars, which is all red because of a red substance that resembles chlorophyll.

Red is the colour of our socialist banner, I [Leonid] said. So I shall simply have to get used to your socialist vegetation.

By describing the minutiae of everyday life on Mars, Bogdanov narrates life in communism as a parallel space odyssey, making communism tangible and popularizing it in much the same way that Tsiolkovsky renders the outcome of his cosmic pursuits by sketching the life of cosmonauts. Bogdanov's text reveals the purpose of this process of rendering utopian life. He wants to create glasses which completely absorb the green waves of light and have the reader recognize in the present historical moment the origins of a society that may be fictional, existing only in an imagined outer space, but whose story is a lens for recognizing the potential of the present. It is a fiction that is intended to drive history.

Bogdanov's text about red glasses is about recognizing that communism is possible, but the notion of red glasses can also refer to the novel itself. Red Star was a vehicle for inciting communist passions and the desire to turn Earth from a green planet into a red one. The transcendental power that drives social change what Tsiolkovksy would call the will of the universe is materialized in science fiction, the kind of science fiction that, as Marx would put it, is meant not only to interpret the world but to change it. Neither cosmist narratives nor their most ambitious and exuberant genre, pre-Revolutionary science fiction, could be called daydreams. Not only did they describe alternative ways of life but they were also used as a tool by which real-life proponents of those alternative ways of life wanted to propel history towards those alternatives. Such narratives were intended both to describe life in utopia and to explain the celestial inevitability of social transformation.

But the idea that socialist utopia is exclusively about collectivism, or that the best way to understand it is to look at what kind of collectives it proposes, has to be reconsidered. To understand the celestial collectivity, one has to start with the representations of the celestial individual the comrade cruising the skies and travelling towards utopia for it is of these individuals that the collectivity consists.

A complex representation of the communist revolutionary can be found in Red Star. The novel describes the Martian community and, through Leonid's story, all the drama and agony inherent in the project of understanding and creating such a community. On his visit to Mars, Leonid cannot process all the impressions, falls ill, and begins hallucinating. Upon recovering, he learns that the Martians are entertaining the idea of killing people on Earth to colonize it, because they think that most Earthlings cannot embrace communist principles. This frightens Leonid, who murders the Martian mastermind of this project and is finally returned to Earth. Our hero ends up in a psychiatric hospital. He is not certain whether he really went to Mars, or whether the entire trip is imagined. But then, in a twist, he is visited again by his Martian friends and given a second chance.