douard

Glissant

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM BLOOMSBURY

Alienation and Freedom, Frantz Fanon

Gilles Deleuze, Postcolonial Theory, and the Philosophy of Limit, Rda Bensmaa

CONTENTS

Quite a number of Glissants theoretical works of the last twenty or so years have not yet been translated into English. In cases where published translations are available, I have used those. Otherwise, the translations of citations from Glissants works included in this book are my own. In both cases, the translated version has been included in the text and the original French included in a footnote, it being important in the case of an author such as Glissant who, moreover, is such a distinctive prose stylist, that the actual wording he himself uses be visible at all times to the reader.

The following abbreviations are used throughout this book for primary source texts by Glissant:

| CL | La Cohe du Lamentin (Gallimard, 2005) |

| DA | Le Discours antillais (Gallimard, 1997 [1981]) |

| EBR | Les Entretiens de Baton Rouge (Gallimard, 2008) |

| IBM | LIntraitable Beaut du monde: adresse Barack Obama (Galaade, 2009) |

| IL | LImaginaire des langues (Gallimard, 2010) |

| IP | LIntention potique (Gallimard, 1997 [1969]) |

| IPD | Introduction une politique du divers (Gallimard, 1996) |

| ME | Mmoires des esclavages (Gallimard, 2007) |

| MPHN | Manifeste pour les produits de haute ncessit (Galaade, 2009) |

| NRM | Une Nouvelle rgion du monde (Gallimard, 2006) |

| PR | Potique de la Relation (Gallimard, 1990) |

| QMT | Quand les murs tombent. LIdentit hors la loi? (Galaade, 2007) |

| SC | Le Soleil de la conscience (Seuil, 1956) |

| TTM | Trait du tout-monde (Gallimard, 1997) |

It will be by now almost a truism that centuries do not always begin and end when their chronological dates indicate. The twentieth century is often thought to have properly begun in political and social terms only at the outbreak of the First World War which, by implication, suggests a rather longer nineteenth century than chronology would have it. It may still be too early to cast judgment on the starting point of the twenty-first century and, in any case, it is unlikely that there will ever be a consensus opinion on the matter as there are a number of significant watershed moments which would seem to be equally worthy contenders. In particular, one might ponder whether it was the demise of the Soviet bloc in the period following the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 and the subsequent end of the Cold War which signalled the end of a short but extremely violent century. Or conversely whether it was the event which came to be known simply as 9/11 in the United States, with the myriad of consequences for global politics which that event has had, that is a more fitting moment to designate as marking the start of the new century.

Either way, it is by now common knowledge that the twenty-first century is going to be fraught with far-reaching problems which humanity will have to at least attempt to mitigate even if it cannot solve them. Whats new, one might retort? Human history was ever thus. This objection to a pessimistic prognosis which is shared by ever-growing numbers of people around the world today would be convincing were it not for a number of factors which are specific to the current conjuncture and which render that conjuncture more problematic when viewed in a long-term perspective than previous bleak moments in human history. To some extent one can set aside contemporary trends which, although nevertheless of major importance, are however perhaps not as decisive for the future of humanity as a whole: the chronic systemic problems which lie at given rise to nationalist anti-globalism reaction in a certain number of Western nations.

Where does the thought of douard Glissant stand in relation to this conjuncture that I have described? I will approach this question by briefly addressing another matter of a general nature: where do minoritarian communities and cultures such as post-colonial communities like those of the francophone Caribbean or those that immigrated into host nations larger than their own stand in relation to such a situation? In this question lie preoccupations which go to the heart of Glissants intellectual project. Indeed the matter of how the situation of post-colonial communities is to be understood is intimately linked in Glissants work to that of immigrant communities for reasons which I will set out. As his oeuvre developed from the late 1980s onwards, the latter question became ostensibly subsumed in the former to some extent, but in reality the matter of the situation of minoritarian cultures in relation to larger and indeed hegemonic cultures remained at the very core of his entire theoretical world view. While up until the 1980s Glissants central preoccupation in this regard was the matter of where a culture like that of Martinique and the other French Caribbean islands stood in relation to their neocolonial master, from Poetics of Relation (1990) onwards it was the standing of all specific cultures in relation to what was the hegemonic economic and hence linguistic preeminence of the United States and the anglophone mindset. The colonialism of former colonial nations like France and Britain had been replaced by another type of imperialism, that which Glissant variously calls standardisationthis new context its concerns were legitimate and, on a point of principle, Glissant would defend the right of all national cultures to their own specificity.

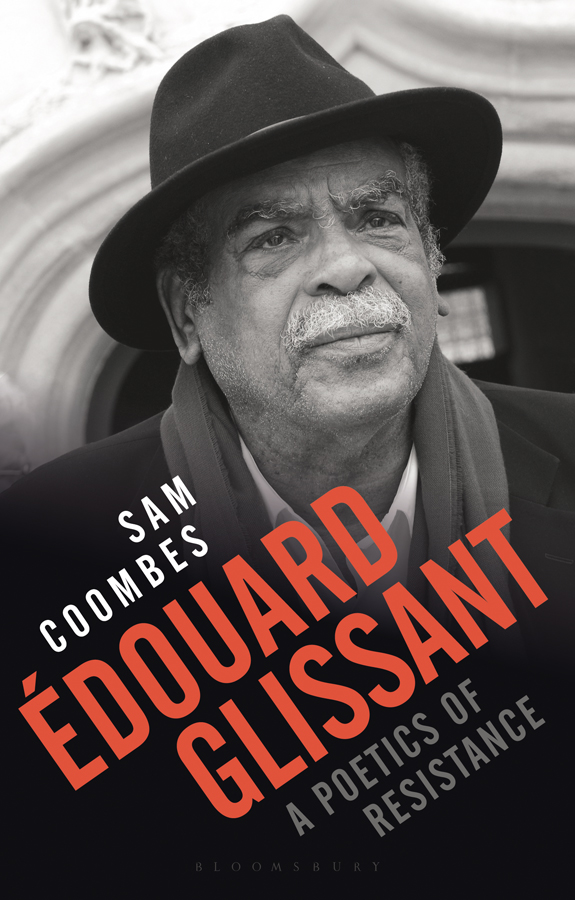

This study aims both to explore Glissants response to the politico-economic arrangement to which the label globalization has commonly been applied over the last twenty-five to thirty or so years, and in some sense to sum up the theoretical contribution that his works of that period constituted. Glissant is considered by many in the field of post-colonial studies to be one of, if not the most significant, thinkers in the francophone context. He died in 2011 after a more than fifty-year career as a publishing author, and it is hence now possible not only to include in our assessment analysis of works published in the later years of his life, which many earlier studies devoted to Glissant could not do, but also to form conclusions about the import of his later oeuvre. I should indicate at the outset that it is the later period of Glissants theoretical writings which form the focus of this study. Although consideration of his poetry and novelistic writings could certainly have been a worthwhile addition to my analyses, Glissants theoretical writings of the last twenty-five or so years constitute a sizeable body of work in its own right and can in my view be discussed independently of the literary works as a stand-alone contribution to theory.

Hence this book aims to serve as an introduction to the later Glissantian theoretical oeuvre for those not familiar with it. It also presents an original view of the central positions set out in that later oeuvre. A defence of Glissant is offered against the criticisms of his later positions, which were made by a certain number of mainly anglophone critical commentators in the early 2000s. The view of the later Glissant which I advocate is grounded in political convictions as is that of these commentators but it involves adopting a stance that is diametrically opposed to theirs. While they have berated Glissant for supposedly abandoning radical politics, I argue on the contrary that radical critique of contemporary globalization is not only accepted by the later Glissant but is also positively encouraged. Far from being an expression of apathy in the face of the growing systemic problems of global capitalism, the later Glissants oeuvre offers vital strategies for countering them and proposes valuable alternatives.