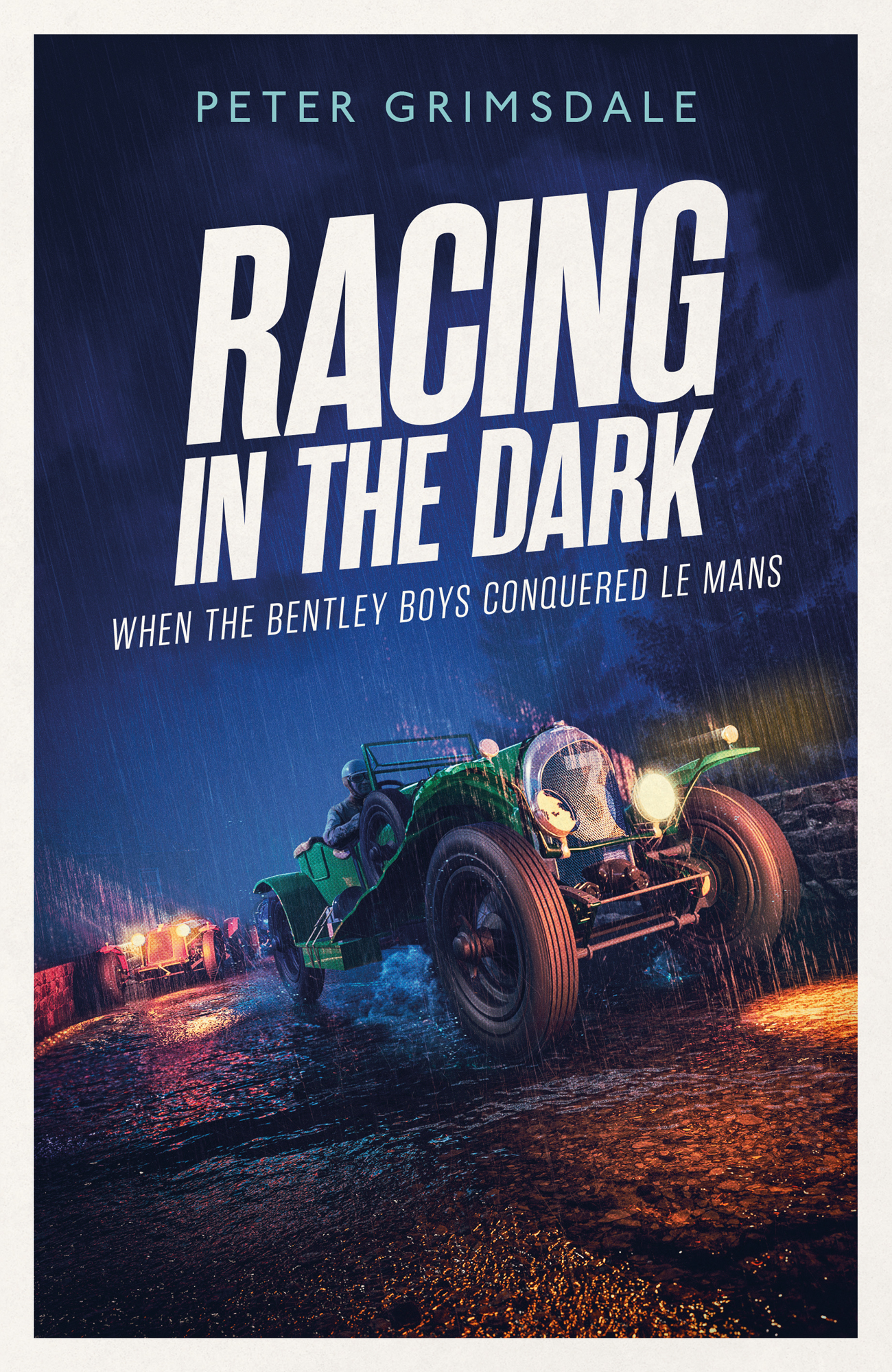

Peter Grimsdale

Racing in the Dark

When the Bentley Boys Conquered Le Mans

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Join our mailing list to get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Vivian

All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake up in the day to find it was vanity, but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dreams with open eyes, to make it possible.

T.E. LAWRENCE , Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Though the machines themselves are interesting beyond belief, it is knowledge of men that counts.

S.C.H. DAVIS , Motor Racing

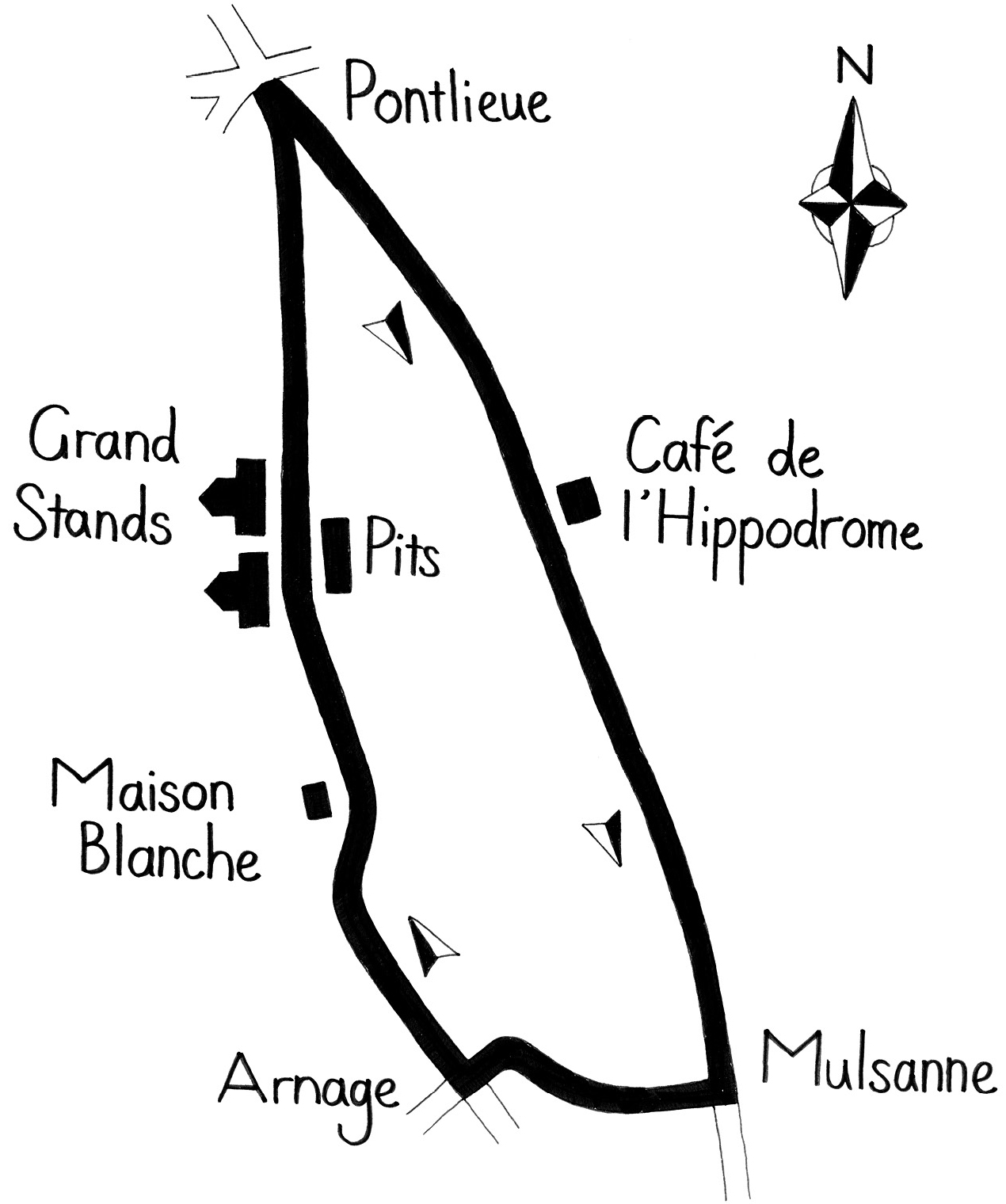

L E M ANS C IRCUIT (192328)

Lap length 10.726 miles

PROLOGUE D UEL ON A G OLF C OURSE

On the 28th of July 1998 at the 19th hole on a golf course outside the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt, two of Germanys most powerful autocrats met to settle a dispute which of them would take control of Britains automotive crown jewel, Rolls-Royce.

Ferdinand Pich was the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche, designer of the Volkswagen. Bullet-headed, with ice-blue eyes, famous in Germany for fathering thirteen children by three wives, Pich was also a formidable engineer. He had designed the Le Mans-winning Porsche 917 as well as the rally-conquering Audi Quattro. And, having rescued Volkswagen from near bankruptcy, he was now on a buying spree, bent on building the biggest car maker in the world. Only the previous month he had acquired Lamborghini and Bugatti.

His rival for the hallowed British brand was Bernd Pischetsrieder, the softly spoken, goateed boss of BMW. A confirmed Anglophile and cousin of Alec Issigonis, designer of the original Mini, he had already scooped up a handful of British brands by buying the remnants of British Leyland.

As a sign of the magnitude of what was at stake, Pich had brought along the premier of VWs home state, Lower Saxony, and alongside Pischetsrieder was the prime minister of BMWs Bavaria, the future Chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder.

All this for a tiny, struggling company with a clapped-out factory that the year before had made only 1,900 cars at a loss.

By the time they emerged from the clubhouse, they had a deal that neither party expected, for there had been an eleventh-hour intervention. Although Rolls-Royce Aerospace had severed almost all their links with the car business, they still controlled the trademark. And having built the Merlin engine that supercharged the Battle of Britain, they were not about to let their name be associated with the producer of Hitlers Peoples Car.

The consequence was a carve-up: BMW would get the Rolls-Royce name only, a brand with a reach out of all proportion to its output and a reputation for excellence unmatched by the current product. Pich and VW, for a cool billion Deutschmarks, got Rolls-Royces antiquated factory in the Cheshire city of Crewe. His consolation prize another piece of British automotive heraldry: Bentley.

Many thought the acquisitive Pich had finally lost his head. Ever since Rolls acquired it in 1931, Bentley had been little more than a product of what the motor industry sneeringly calls badge-engineering the famous flying B grafted on to a slightly rounded-off version of the Grecian Rolls-Royce grille. But Pich was doing something he rarely ever did; he was smiling. He had forced his board into letting him make an offer no one could refuse. One billion marks is cheap, he insisted.

What did he think he was buying?

Being a details man, Pich could answer that question with typically withering precision. He could point to an exact moment not just a year or a day, but an exact time 9.28 p.m. on 18 June 1927. And a location, between the villages of Arnage and Pontlieue in the Sarthe region of France, a whitewashed single-storey building known as Maison Blanche. For it was at that place at that time that a motor car designed by Walter Owen Bentley found fame. And that is where this story begins.

1 D ANGEROUS M EN

The race had been underway for six hours: another eighteen to go. Dusk settled over the Le Mans circuit. Behind the pit counter, Walter Owen W.O. Bentley glanced again at the stopwatch hanging from a leather strap around his neck, then stared back to where the empty stretch of track disappeared into the darkness. Apart from the dull thump inside his head, there was nothing but silence.

They were late all of them. All of his cars.

One of the three timekeepers looked up at his boss, perched on a stool just behind them. W.O.s lips were pressed tightly together, his face white in the ghostly glow of the French army arc lights that illuminated the darkening pits. He was a man of few words at the best of times, and this was not the best of times. His mind raced, but he said nothing.

His first thoughts were for his drivers, Callingham, Duller and Davis. There had already been one fatality and four injuries that weekend. As the seconds climbed towards a full minute, the enormity of what was happening started to sink in. For one car to be overdue was not unusual, but for all three

The Bentleys had led from the start. The latest model, the 4 Litre, had smashed the lap record at a commanding 73.2 mph, while the two 3 Litre cars kept close. W.O.s machines were fast but durable, his drivers prudent and drilled not to cane the vehicles, in the hope that they would last the full twenty-four hours an awesome feat in 1927. But now, along with his fears for the drivers, back came his misgivings about being there at all.

The previous two years events had been pure humiliation; none of the Bentleys finished either race. In 1926 S.C.H. Davis ploughed car number 7 into a sandbank just minutes from the flag. After that, W.O. vowed to give up racing and put the team cars up for sale. But Daviss co-driver Dudley Benjafield was determined to have another go. He bought Old No. 7 and put his name down for the 1927 event, as a privateer. In the end W.O. succumbed, unable to resist one more crack at Les Vingt-Quatre Heures du Mans, like a gambler pushing all his chips onto one number. And once again he was staring into a void.

In its eight years of existence, Bentley Motors had yet to make a penny. Only a last-minute bailout had saved it from collapse. Common sense should have told W.O. to focus on building and selling more cars to turn that elusive profit. But other forces were at work.

W.O., Davis and Benjafield, born in the reign of Queen Victoria, enjoyed a lifestyle undreamed of by their ancestors as Britain crested the wave of imperial prosperity and industrial progress. But that carefree life had been vaporised in the cataclysm of world war.

![[美]乔恩·本特利(Jon Bentley) 著 - 编程珠玑(第2版·修订版)](/uploads/posts/book/275588/thumbs/jon-bentley.jpg)