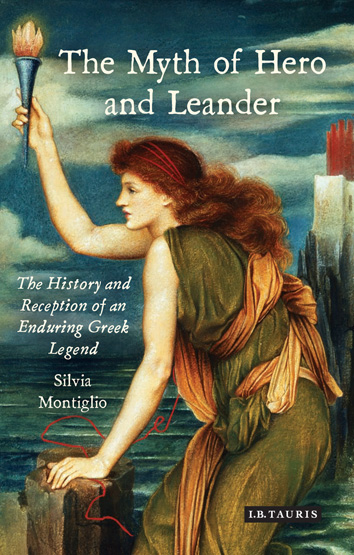

SILVIA MONTIGLIO is Basil L. Gildersleeve Professor of Classics at Johns Hopkins University. Her previous books include Silence in the Land of Logos (2000, paperback 2010); Wandering in Ancient Greek Culture (2005); From Villain to Hero: Odysseus in Ancient Thought (2011); Love and Providence: Recognition in the Ancient Novel (2013); and, most recently, The Spell of Hypnos: Sleep and Sleeplessness in Ancient Greek Literature (I.B.Tauris, 2015).

This is a beautifully researched and richly articulated discussion of the fortunes of a late-blooming classical myth that for over a millennium Europe found itself unable to put down. The Myth of Hero and Leander is an exemplary reception history in the best sense of the term.

GORDON BRADEN, Emeritus Professor of English, University of Virginia

With sure scholarship and lively critical insight, Silvia Montiglio engagingly traces the?reception of the story up to the end of the fifteenth century: in Latin, European vernacular and Byzantine Greek rewritings.

PHILIP HARDIE, Honorary Professor of Latin, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge

Long before Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, there was the tragic love story of Hero and Leander. Europe and Asia, West and East, love and death: Silvia Montiglio explores these grand themes in her thrilling analysis of the star-crossed lovers and their cruel fate. Nothing like it exists in English, or indeed in any language. The book is a gold mine of information: detailed, accomplished and insightful.

PHIROZE VASUNIA, Professor of Greek, University College London

THE MYTH OF

HERO AND

LEANDER

The History and Reception of an

Enduring Greek Legend

S ILVIA M ONTIGLIO

Published in 2018 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2018 Silvia Montiglio

The right of Silvia Montiglio to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

Library of Classical Studies 19

ISBN: 978 1 78453 956 6

eISBN: 978 1 78672 290 4

ePDF: 978 1 78673 290 3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

To Don Juedes

Bibliothcaire extraordinaire

Contents

Illustrations

Rubens, Hero and Leander, c.1607, Yale University Art Gallery. Credit: Gemldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany Staattliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden / Bridgeman Images.

William Henry Rinehart, Hero (1866), Washington, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Credit: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Peabody Institute.

Frederic Leighton, The Last Watch of Hero (1887), Manchester Art Gallery. Credit: Manchester Art Gallery, UK / Bridgeman Images.

).

Pierre-Claude Delorme (17831859), Hro et Landre, Brest, Muse des beaux-arts. Credit: Muse des beaux-arts de Brest mtropole.

William Etty, Hero, Having Thrown Herself from the Tower at the Sight of Leander Drowned, Dies (1829), Tate Gallery. Credit: York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery), UK / Bridgeman Images.

).

The two illustrations contained in the 1517 Aldine edition of Hero and Leander. Source: Aldo Manuzio and Andrea Torresano (eds), Mousaiou poimation ta kath' Hero kai Leandron. Orphes Argonautika. Tou autou Hymnoi. Orpheus peri lithn. Musaei opusculum de Herone & Leandro. Orphei Argonautica. Eiusdem hymni. Orpheus de lapidibus (Venice, 1517).

Domenico Fetti, Hero and Leander (c.1621), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Credit: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria / Bridgeman Images.

Acknowledgements

Writing this book has been an exciting journey but at times on rough waters, and if I have not drowned, it is thanks to the beacons held by supportive friends and colleagues. A section of ) on audiences at the Fifth International Conference on the Ancient Novel in Houston, at the Classical Association in Canterbury and at the University of Crete in Rhethymno. At Johns Hopkins, Martijn Buijs and Kristina Mueller have offered invaluable help with translations from old Dutch and German, and Michele Asuni, Ryan Franklin and Jonathan Meyer have contributed insightful observations in the classroom. Gordon Braden, Phiroze Vasunia and a third, anonymous reader have been supportive of this project, as has Alex Wright, senior editor at I.B.Tauris. I owe him special thanks also for his patience and cheerfulness all along. To him, to his colleague Thomas Stottor and to Robert Wagman at the University of Florida goes my gratitude for helping me in various ways with securing the images. A warm thank you to Mary Whiting, who has read the entire manuscript and lavished her finesse and erudition on it. My love and thanks, as always, to Gareth Schmeling, whose light shines in the darkest sky. Finally, I dedicate this book to Don Juedes, librarian at Johns Hopkins, for all his competent and generous help over the years. He is, truly, an extraordinary librarian.

Introduction

Ne vous sans moi

Ne moi sans vous

Marie de France, Chevrefoil

THE SCOPE OF THIS BOOK

Like Pyramus and Thisbe or Romeo and Juliet, Hero and Leander are star-crossed lovers. She lives secluded in a tower in the city of Sestos on the European side of the Hellespont and he in Abydos on the Asian side. Since they cannot hope to marry, they resolve to meet in secret: each night he swims across to her, guided by the light of her torch, and at daybreak he swims back to Abydos. But one winter storm kills both the lamp and Leander. Hero, who has spent the whole night anxiously straining her eyes over the sea, at dawn sees his mangled body washed ashore and hurls herself from the tower to meet him in death.

This story has enjoyed great popularity from antiquity to the twenty-first century, and in every possible medium. Marlowe's effervescent, erotic and somewhat comic poem, which Seamus Heaney imaginatively called a work happily in love with its own own inventions,

To English-speaking readers (and not only them) this athletic ritual will conjure up its first and most famous celebrant: Lord Byron, who during his grand tour made it across the Hellespont on his second attempt and became so proud of his accomplishment that he could not refrain from recording it over and over. He had not just overcome his physical disability (he was born with a clubfoot) as well as cold and strong currents but had also, as one critic perceptively notes, made a legendary tale real in his own person: In re-enacting Leander's exploit, Byron temporarily became the hero of an ancient legend, a character in a treasured story. His best-known account of his feat, however, is not boastful but delightfully ironic:

If, in the month of dark December,

Next page