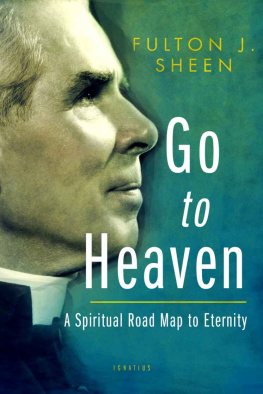

GO TO HEAVEN

FULTON J. SHEEN

GO TO HEAVEN

A Spiritual Road Map to Eternity

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original edition published by Dell Publishing, New York

1949, 1958, 1960 by Fulton J. Sheen

All rights reserved

Copyright permission was granted by

The Estate of Fulton J. Sheen / The Society for the Propagation

of the Faith

www.onefamilyinmission.org

Nihil obstat : John A. Woodwine, J.C.D., Censor Librorum

Imprimatur : Francis Cardinal Spellman, Archbishop of New York

August 10, 1960

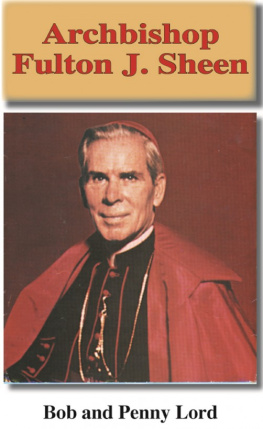

Cover photograph of Fulton J. Sheen

by Fabian Bachrach (1965)

Peoria Star Journal Archives

Cover design by Enrique Javier Aguilar Pinto

Reprinted in 2017 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-62164-154-4 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-776-1 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2017931781

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated to the LADY who looked down to Heaven

As she held Heaven in her arms

CONTENTS

GO TO HEAVEN

If Horace Greeley had not believed there was such a thing as territory beyond the Mississippi, he would never have said: Go west, young man. If the modern man did not believe there was such a thing as hell, he would never give so many directives to those to whom he did not like to go there. Nobody ever says: Go to heaven. That is why we propose in this book to reverse the direction. As a matter of fact, neither hell nor heaven is related to our lives as arbitrary punishments or rewards.

Hell is not related to an evil life, as is generally supposed, as a spanking is related to an act of disobedience, for a spanking need not necessarily follow disobedience, and rarely does in juvenile circles. Rather, hell is related to an evil life as blindness is related to the plucking out of an eye. Heaven is not related to a good life as a medal is related to a school examination; it is rather related to a good life as knowledge to study. By the mere fact that we apply ourselves intellectually, we become learned.

This book is a road map to heaven and follows a very definite pattern. Many of the ideas contained herein have appeared in our previous writings, but they are here ordered in the forms of steps to the Kingdom of Light. The book opens with the story of man full of certain tensions and complexes originating from the conflict between what he ought to do and what he actually does. Once man recognizes that he cannot escape this civil war within by lifting himself by his own psychological bootstraps, he sees that supra-human aid is possible. There is a Truth beyond the reach of his mind and a Power beyond his tepid and weak will. This Truth and this Power are gifts. Mans quest for God, however dim it is, is seen to be answered by Gods quest for man.

Once there is this divine romance between divinity and mankind in the person of Christ, there arises the great question confronting every man: Will he appropriate to himself this Divine Life, which is gratis and, therefore, called grace, or will he reject it?

Life is a tremendous drama in which one may say, Aye or Nay to his eternal destiny. To admit light to the eye, music to the ear, and food to the stomach is to perfect each of these organs; so too, to admit Truth to the mind and Power to the will is to make us more than a creature, namely, a partaker of the Divine Nature.

From that point on, the signposts to Heaven are clearly marked in succeeding chapters. Some say we have our hell on this earth. We do. We can start it here, but it does not finish here. But heaven has its beginnings here in a true peace of mind in union with Divine Life, but it does not finish here either. That is why we offer the encouragement: Go to Heaven.

The First Faint Summons to Heaven

Men of other generations went to God from the order in the universe; the modern man goes to God through the disorder in himself. The modern soul no longer looks to find God in nature. In other generations, man, gazing out on the vastness of creation, the beauty of the skies, and the order of the planets, deduced the power, the beauty, and the wisdom of the God Who created and sustained that world. But the modern man, unfortunately, is cut off from that approach by several obstacles: he is impressed less with the order of nature than he is with the disorder of his own mind; the atomic bomb has destroyed his awe of nature; and, finally, the science of nature is too impersonal for this self-centered creature. It is the human personality, not nature, which really interests and troubles men today.

This change in our times does not mean that the modern soul has given up the search for God, but only that it has abandoned the more rational, and even more normal, way of finding Him. Not the order in the cosmos, but the disorder in himself; not the visible things of the world, but the invisible frustrations, complexes, and anxieties of his own personalitythese are the modern mans starting point when he turns questioningly toward religion. In happier days, philosophers discussed the problem of man; now they discuss man as a problem.

Formerly, man lived in a three-dimensional universe where, from an earth he inhabited with his neighbors, he looked forth to heaven above and to hell below. Forgetting God, mans vision has lately been reduced to a single dimension; namely, that of his own mind.

Where can the soul go, now that a roadblock has been thrown up against every external outlet? Like a city which has had all its outer ramparts seized, man must retreat inside himself. As a body of water that is blocked turns back upon itself, collecting scum, refuse, and silt, so the modern soul (which has none of the goals or channels of the Christian) backs upon itself and in that choked condition collects all the subrational, instinctive, dark, unconscious sediment which would never have accumulated had there been the normal exits of normal times. Man now finds that he is locked up within himself, his own prisoner. Jailed by self, he now attempts to compensate for the loss of the three-dimensional universe of faith by analyzing his mind.

The complexes, anxieties, and fears of the modern soul did not exist to such an extent in previous generations because they were shaken off and integrated in the great social-spiritual organism of Christian civilization. They are, however, so much a part of modern man that one would think they were tattooed on him. Whatever his condition, the modern man must be brought back to God and happiness. If the modern man wants to go to God from the devil, why, then, we will even start with the devil: that is where the Divine Lord began with Magdalen, and He told His followers that, with prayer and fasting, they too could start their evangelical work there.

There is no difference except that of terminology between the frustrated soul of today and the frustrated souls found in the Gospel. The modern man is characterized by three alienations: he is divided from himself, from his fellow man, and from his God. These are the same three characteristics of the frustrated youth in the land of the Gerasenes.

The first of these is self-estrangement. The modern man is no longer a unity, but a confused bundle of complexes and nerves. He is so dissociated, so alienated from himself that he sees himself less as a personality than as a battlefield where a civil war rages between a thousand and one conflicting loyalties. There is no single over-all purpose in his life. His soul is comparable to a menagerie in which a number of beasts, each seeking its own prey, turn one upon the other. Or he may be likened to a radio that is tuned in to several stations; instead of getting any one clearly, it receives only an annoying static.

If the frustrated soul is educated, it has a smattering of uncorrelated bits of information with no unifying philosophy. Then the frustrated soul may say to itself: I sometimes think there are two of mea living soul and a Ph.D. Such a man projects his own mental confusion to the outside world and concludes that, since he knows no truth, nobody can know it. His own skepticism (which he universalizes into a philosophy of life) throws him back more and more upon those powers lurking in the dark, dank caverns of his unconsciousness. He changes his philosophy as he changes his clothes. On Monday, he lays down the tracks of materialism; on Tuesday, he reads a best seller, pulls up the old tracks, and lays the new tracks of an idealist; on Wednesday, his new roadway is communistic; on Thursday, the new rails of liberalism are laid; on Friday, he hears a broadcast and decides to travel on Freudian tracks; on Saturday, he takes a long drink to forget his railroading, and on Sunday, ponders why people are so foolish as to go to church. Each day he has a new idol, each week a new mood. His authority is public opinion; when that shifts, his frustrated soul shifts with it. There is no fixed ideal, no great passion, but only a cold indifference to the rest of the world. Because he lives in a continual state of self-reference, his conversational Is come closer and closer, as he finds all neighbors increasingly boring if they insist on talking about themselves instead of about him.

Next page