The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

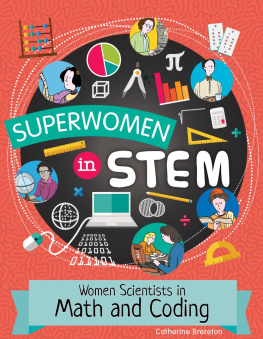

Alexa Canady, the first female African American neurosurgeon, once said, The greatest challenge I faced in becoming a neurosurgeon was believing it was possible.

It takes many years of dedication and hard work to become an important scientist, artist, engineer, or doctor. To achieve a first, however, takes a willingness to push beyond what seems possible.

The people featured in this book did just that. Well take a look at fifty pioneers who pushed past the established thinking of their time, past gender and racial barriers, to become a first in the fields of science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics.

These great thinkers and visionaries came from all walks of life. Some, like computer scientist Alan Turing, were child prodigies. Others, like John Herrington, the first Native American in space, discovered their calling as adults. Youll meet inventors whose groundbreaking technology revolutionized our modern world and artists whose works have inspired countless others.

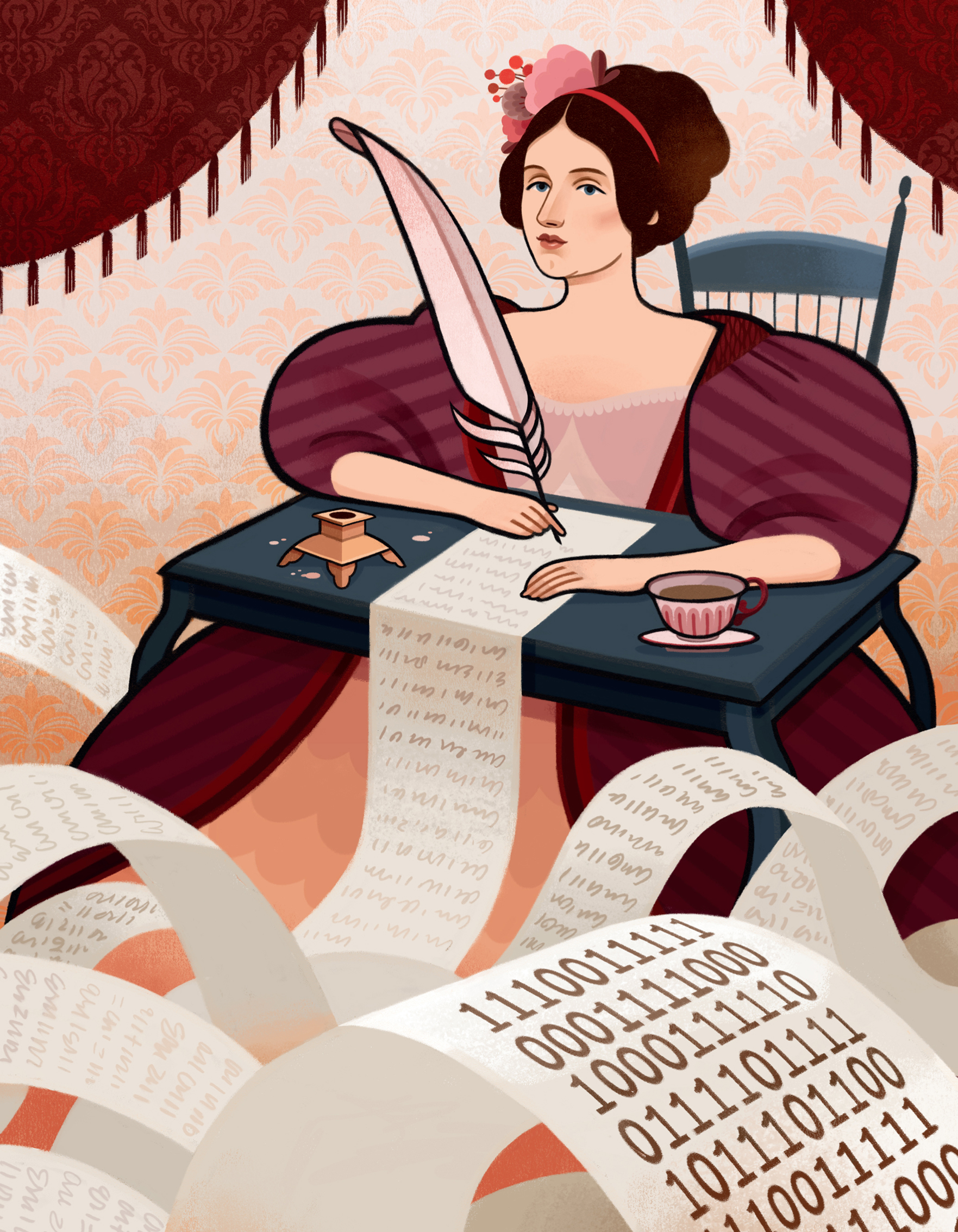

It can be a lonely path, being the first. Sometimes, it means waiting for the rest of the world to catch up. Youll meet Ada Lovelace, who wrote the first computer program before modern computers even existed, and the geologist Walter Alvarez, whose theory about dinosaur extinction was mocked for years before it became universally accepted.

Even with so many incredible firsts already accomplished, the world still awaits many more. Who will be the first person to travel to Mars, to construct an artificial mind, or to cure cancer?

We hope these stories inspire you to build on yesterdays achievements, to resist todays boundaries, and to dream beyond what seems possible.

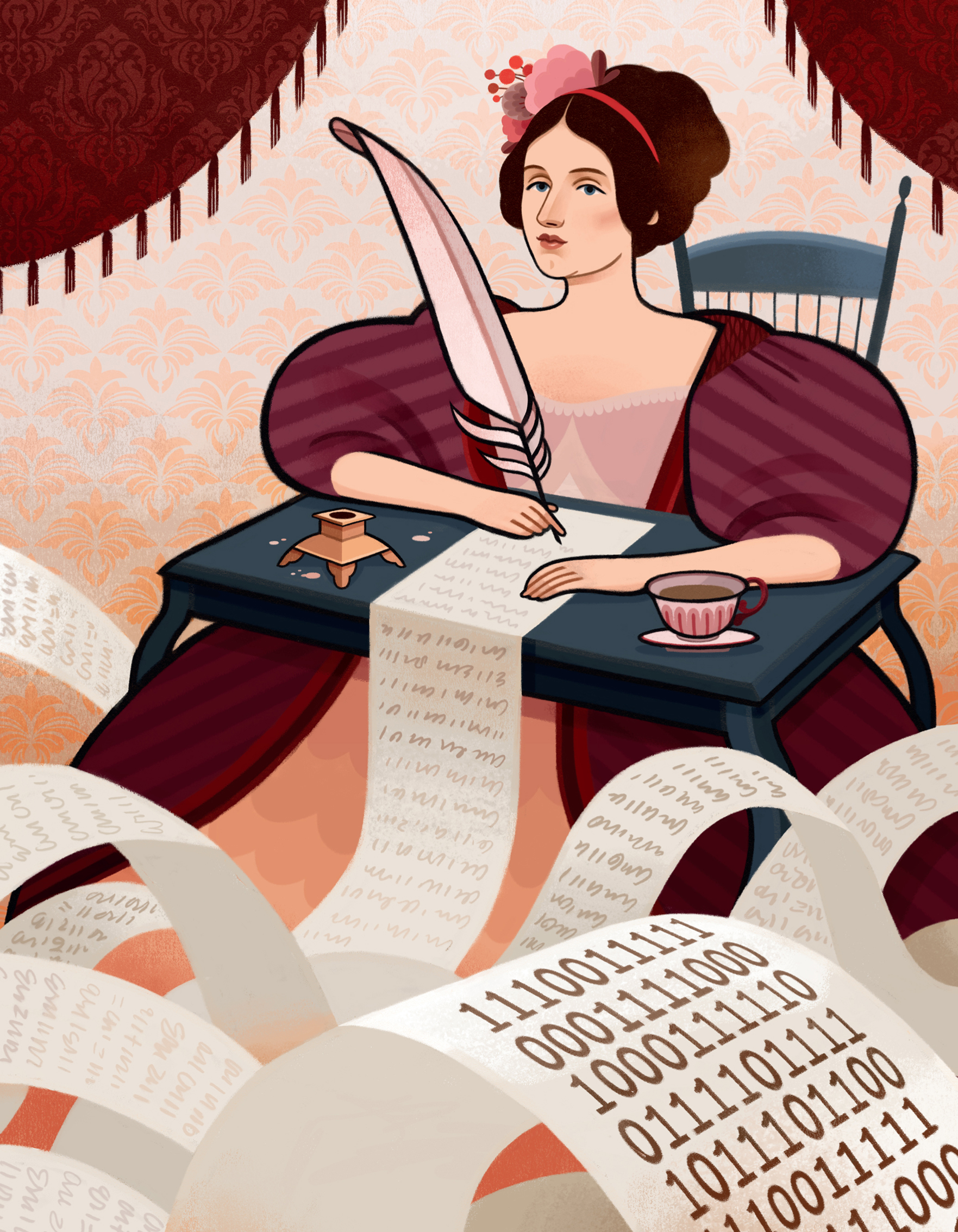

THE FIRST PERSON TO CREATE A COMPUTER PROGRAM (1843)

If you cant give me poetry, cant you give me poetical science?

Growing up, Ada Lovelace was monitored carefully for any signs of misbehavior. That was because her father was none other than Lord Byron, a famed Romantic poet with a bad reputation. Her mother wanted to make sure her daughter would not follow in her fathers footsteps, and she put Ada on a strict education of math and science. Nonetheless, young Ada found imaginative ways to apply her scientific learnings. At age twelve, she crafted plans for a personal flying machine, researching materials and studying the wings of birds.

When she was seventeen, Ada met prominent inventor Charles Babbage. At the time, he was in the middle of creating a machine called the Difference Engine. Babbage envisioned a device, composed of gears and cogs, that could process high-level computations. In other words, Babbage was working on the worlds first computer.

Ada was fascinated, and the two struck up a lifelong friendship and collaboration. When Charles began work on an even more complex Analytical Engine, Ada could see the machines potential uses beyond number crunching. Ada was the first to theorize that computing machines could be used to process all sorts of informationincluding music and art.

Ada set about writing down a sequence of instructions that Babbages machine could eventually run, called an algorithm. And for that work, she is known as the worlds first computer programmer. Babbage never finished building his Analytical Engine, and Ada was unable to test her theories in her lifetime. However, Adas grand vision for computers proved quite true in time.

THE FIRST FEMALE PROFESSOR OF ASTRONOMY IN THE UNITED STATES (1865)

We especially need imagination in science. It is not all mathematics, nor all logic, but it is somewhat beauty and poetry.

Maria Mitchell was born into a large family of Quakers who valued education for girls just as much as for boys. Marias father taught her astronomy in their Nantucket, Massachusetts, home using his personal telescope. At age twelve, she helped him calculate the exact position of their home using a solar eclipse. By age fourteen, she was assisting Nantuckets sailors with their navigational computations, which were vital in helping them find their way home from long whaling journeys. As an adult, Maria studied the sky every clear night, tracking stars and planets.

On October 1, 1847, Maria left a party at her parents house to visit the rooftop observatory she and her father had built above a bank. When she peered through her telescope, Maria spotted a small and blurry object, just above the North Star, that did not appear on her charts. After confirming with her father, she realized she had discovered her first comet, later called Miss Mitchells Comet after her.

Maria published a notice of her discovery, initially under her fathers name. The discovery launched her into new academic circles among astronomers and other scientists. She was even honored with a gold medal by the king of Denmark. Job opportunities followed, and Maria was about to turn her passion for astronomy into a lifelong career. In 1848, she became the first woman to be elected into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. And in 1865, Maria Mitchell became an astronomy professor at the newly founded Vassar College, making her also the first female astronomy professor in the United States.

THE FIRST PERSON TO CROSS THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE (1883)

I HAVE MORE

BRAINS,

common sense,

AND KNOW-HOW GENERALLY THAN

ANY TWO ENGINEERS

CIVIL OR UNCIVIL

that I have ever met.

Emily Warren Roebling perhaps did not intend to help build one of the most famous bridges in the world. Born in 1843 to an esteemed family in Putnam County, New York, Emily received a proper education growing up. For young ladies of her time, this included housekeeping and sewing, in addition to history and algebra.

In 1865, she married a soldier named Washington Roebling. Emilys new father-in-law happened to be John Augustus Roebling, a civil engineer famous for his suspension bridges. He had just finished a design for a bridge connecting Brooklyn to Manhattan. But after an accident, John died before the project could get started. Emilys husband took over the project for his father. Within just a few years, however, bad luck struck him as well. He developed caissons disease, also known as decompression sickness, from his work in one of the underwater structures (caissons) of the bridge, which quickly left him bedridden.

So Emily stepped in. She began researching the technical issues, learning about the strength of the materials being used, and stress-testing structures. She went to the build site every day to relay instructions from her husband. Emily became so good at managing the project that many suspected she actually was the brains behind the bridge.