About the Authors

Rob Eastaway has written several bestselling books that connect maths with everyday life, including Why do Buses Come in Threes?, the bestselling Maths for Mums and Dads for parents with primary schoolchildren, and More Maths for Mums and Dads for parents with teenage children. He appears regularly on the radio and has given talks about maths across the UK to audiences of all ages, at locations ranging from the Royal Exchange Theatre to Pentonville Prison. Married with three children, he lives in south London.

Mike Askew is Distinguished Professor of Mathematics Education, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Until recently he was Professor of Primary Education at Monash University, Melbourne and previously Professor of Mathematics Education at Kings College, University of London. A former primary school teacher, he now researches, speaks and writes on teaching and learning primary mathematics. For the Academic year 2006/07 he was Visiting Distinguished Scholar at City College, City University New York. He is also a skilled magician.

About the Book

Need some help with addition? Play a game of Salute

Having trouble with times tables? Try Times Table Donk

Floundering with fractions? Get creative cutting up the toast with your kids at breakfast

Busy mums or dads are crying out for quick and easy ways to help their children with primary school maths and beyond. Here are 101 simple tips, games and activities to make practising maths as engaging and enjoyable as possible, for you and your child. All can be incorporated into the everyday routine at home and on the go with minimal fuss and no expensive kit helping children have fun with numbers. Indeed, most of the time they wont even realise that maths is involved. Sneaky!

Areas covered include, addition and subtraction, multiplication and division, fractions, ratio and proportion, telling the time, estimation, measurement, geometry and shapes, with an emphasis on problem solving throughout.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to: Andrew Jeffrey, Rob Elias, Cath Frances, Alison Young, Ed Faulkner, Mary Chamberlain, Eugenie Todd, Tom Hancock, Rachel ORiordan, James Gooding, Becky Lovelock, Hugh Hunt, Elaine Standish and Pete Sanders.

And to Jenna, Adam and Josie for being such willing guinea pigs.

Age Key

As a guide, weve provided a key for each activity suggesting which ages it is best suited to. Some activities can work (with a bit of adapting) for everyone, but others are much more age specific, for example because they are based on more sophisticated maths knowledge.

all ages

all ages

three to four year-olds (Pre-school, Reception)

three to four year-olds (Pre-school, Reception)

five to six year-olds (Year 1/2)

five to six year-olds (Year 1/2)

seven to eight year-olds (Year 3/4)

seven to eight year-olds (Year 3/4)

nine to ten year-olds (Year 5/6)

nine to ten year-olds (Year 5/6)

eleven plus year-olds (Year 6+)

eleven plus year-olds (Year 6+)

So:  means this activity is best suited to seven to ten year-olds.

means this activity is best suited to seven to ten year-olds.

Also by Rob Eastaway and Mike Askew

Maths for Mums and Dads

More Maths for Mums and Dads

1

Playing Dumb

Give your child a chance to answer before you do

Helps with: Building your childs confidence, particularly when doing money calculations.

When youve posed a maths question for example, If this cost eighty-four pence, how much change will there be from a pound? the silence that follows can be painful. It can be tempting either to hurry your child along (Come on, what do you have to add to eighty-four to make a hundred?) or to answer the question yourself. The trouble is that this knocks your childs confidence, so try to resist the temptation always to be the expert who knows the right answer. It can be much more effective to treat a calculation as a collaboration, something you and your child are doing together, rather than a test.

One tactic is to play dumb: to attempt the question you want answered yourself, but get stuck. Start going through your thinking, but then make an error and correct yourself. Lets see, eighty-four from ninety is five is that right? eighty-four plus five is no, thats eighty-nine. This is inviting your child to help you.

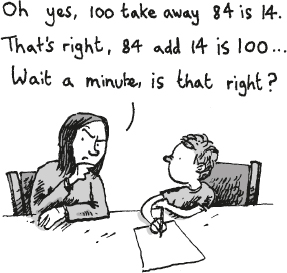

If they come up with an answer before you do, and they get it wrong, start by accepting the answer. Oh, yes, a hundred take away eighty-four is fourteen. Thats right, eighty-four add fourteen is a hundred Wait a minute, is that right ?

(All of this can be done mentally, but most children find it helpful to see calculations written down. This is where a graffiti wall can come in very handy see .)

2

Saying Yet

The best response to the phrase I cant is the word Yet

Helps with: Building confidence in solving maths problems, realising that finding maths hard is OK.

Sometime in your childs maths career possibly very early on they are going to encounter some maths that is hard. Maybe it will be doing short division, or working out how to add fractions. What it leads to is the complaint, I cant do it! And the simple response to that is the word yet. You cant add fractions yet, you dont get all your divisions right yet. That simple word encourages what teachers like to call a growth mindset, in other words maths is something you get better at with practice, rather than something you can either do or not do. A bit like playing the piano.

This tip comes in most handy at homework time, but it applies anywhere and to anything that your child is struggling with not just maths.

3

Think Aloud

When doing calculations, think aloud

Helps with: Understanding that answers dont appear by magic, but need to be worked out and also that theres more than one way of getting to the right answer.

If your child is with you when you are working out the answer to something, make a point of doing it out loud. If you happen to be very good at mental calculations, slow down a bit so they can follow what you are doing. This will send a very positive message that you need to work at getting to a solution and also that there can be several different ways of doing so.

By calculating aloud you are also being a good role model your child will feel its normal to do the same. Its especially good if you occasionally make mistakes, so that they can see that mistakes are normal and nothing to be ashamed of (though you do want the right answer in the end, of course).

4

all ages

all ages three to four year-olds (Pre-school, Reception)

three to four year-olds (Pre-school, Reception) five to six year-olds (Year 1/2)

five to six year-olds (Year 1/2) seven to eight year-olds (Year 3/4)

seven to eight year-olds (Year 3/4) nine to ten year-olds (Year 5/6)

nine to ten year-olds (Year 5/6) eleven plus year-olds (Year 6+)

eleven plus year-olds (Year 6+) means this activity is best suited to seven to ten year-olds.

means this activity is best suited to seven to ten year-olds.