CONTENTS

Also by Rob Eastaway and Mike Askew

Maths for Mums and Dads

INTRODUCTION

Your child has made it through primary school. While they were there, you probably discovered the new-fangled methods for arithmetic, such as chunking and the grid method; you might even have discovered that some of these modern methods are easier to understand than the traditional ones.

But when your child embarks on maths at secondary school, two new issues arise. First, in the build-up to GCSE, school children begin to do maths that you have never encountered before or if you have, you have long since forgotten it. Factorising equations? Finding the locus? Solving for x? What do these even mean?

And the second problem? As your child becomes a teenager, two dreaded questions increasingly loom: When will I ever need this? And even worse: Who cares?

And since the standard answer to these questions is often You will find this useful one day if you go on to be such and such (response: But Im not going to be a such and such) things can become extremely fraught.

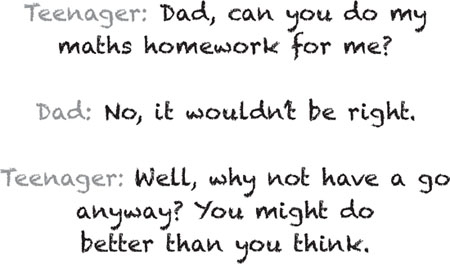

Also of course your teenager might well say that they dont actually want your help. This is partly because you are their parent and they want as little interaction with you as possible; but also perhaps because they dont believe that you can help, either because they think you wont understand or because youre only going to confuse them by showing them different methods from the ones they do at school. (Both of these might be true.)

This book will help you with both problems dealing with your childs attitude towards maths, as well as getting to grips with the maths yourself. We explain in straightforward terms the maths your child will encounter in their early teens. In many cases we give examples of where maths crops up in the real world. and for those topics that are more abstract well suggest ways to find some meaning in the maths. And well suggest strategies to make your teenager more likely to engage with maths and engage with you.

(By the way, were aware that if you happen to leave this book lying around at home, your teenager might get curious and want to dip into it. This mightnt be a bad strategy.)

A word of warning, however: this is NOT a textbook. The secondary curriculum is very broad, different schools teach the same topics in different ways, and it isnt possible to cover every single angle (excuse the pun) in this book. But if you want to know what is the point of, say, algebra and why a teenager should even bother to grapple with it in the first place, this book might be a better place to start.

If these somehow passed you by, the methods and their rationale are covered in Maths for Mums and Dads.

PART ONE

MATHS, PARENTS & TEENAGERS

WHAT TEENAGERS SAY

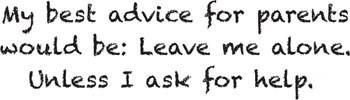

MOST OF THE parents we talked to want to help their teenagers. Unfortunately, in talking to teenagers we found that a lot of them didnt want parental help. Its easy to assume that this is because many teenagers want to have as little contact with their parents as possible, but we discovered a variety of reasons why some would rather their parents leave them alone when it comes to maths. Two common reasons were summed up by these quotes from teenagers:

They just confuse me because they try to teach me ways that are different from the ones we learn at school.

They dont understand it themselves and so I have to wait around for ages while they try to work it out.

Another reason why teenagers avoid parents was nicely hinted at by this frustrated dad:

Typically, my children want me to just quickly tell them the answer, whereas I want to explore the question, make sure they understand ideas, can demonstrate the method and why the answer is as it is.

From a teenagers point of view this often comes across rather differently.

I like asking Mum because she just gives me the answer, whereas Dad always wants to give me a lecture.

On the other hand, many teenagers get frustrated by maths precisely because they do want to understand the bigger picture but get told instead not to worry about that and just learn a technique. So when your teenager does come to you for help, its worth asking what sort of help they want the quick fix or a chance to discuss what its about.

Is there a different way to deal with boys and girls? There are two common stereotypes, that boys just want the quick answer, while girls need to understand and want to be careful and tidy. However, the reality is that there is as much variation within genders as between them. When we asked fourteen-year-olds to tell us the difference between the way boys and girls do maths, the most common answer was that there is no difference, and that it depends on the individual. Youll know what motivates your teenager.

Fast and Slow Thinking That Sinking Feeling

Most parents are only too aware that teenagers confronted with maths homework can get particularly grumpy. What is it about maths that makes it so prone to that sinking feeling (as one teenager described it)?

Theres a particular question that gives a clue. Have a go at it:

THE BOW AND ARROW QUESTION

THE BOW AND ARROW QUESTION

A bow and an arrow cost 11 in total. The bow costs 10 more than the arrow. What does the arrow cost?

You probably came up with an answer to this question almost instantly. Teenagers certainly do.

If your answer is 1, then you agree with the vast majority of teenagers and adults.

But if 1 is your answer, just think for a second. The bow costs 10 more than the arrow, so if the arrow cost 1 then the bow cost 11, so their combined cost is 12. Thats not right: the question said that the combined cost is 11.

When you realised that 1 was the wrong answer, did you pause before reading on and try to work out the actual price? Or did you react as many teenagers do: its not possible or its a trick or even this reminds me of why I dont like maths.

These negative reactions are very common, and they give an important clue about the difficulties that many teenagers have with maths.

Theres some psychology here. The Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman has found strong evidence that our minds operate on two systems, one that is fast and intuitive and a second that is slower and deliberate. Fast thinking is about intuition, and this type of thinking tends to dominate, even though we dont always recognise that this is the case. Slow thinking involves being analytical, and requires increased effort and concentration.

The Bow and Arrow puzzle is an example of where our fast intuitive thinking takes over, but turns out to be wrong, and so we have to switch over to slow mode to figure out the solution. Most of us spend much more time thinking fast (intuitively) than we realise, and find thinking slow (analytically) a challenge. This is even more the case for teenagers, and the constant battle between fast and slow that maths forces on them is one reason why they find it so hard.

So what can parents do about it?

First, being aware of the way that theyre thinking is a great help to working with them and lessening that sinking feeling. But its also important to realise that there is a positive side to slow thinking. Many people report that when they get engaged in activities like maths or writing or painting they cease to be aware of the passage of time whats sometimes referred to as a state of flow. And research suggests flow states can lead to a tremendous feeling of satisfaction.

Next page

THE BOW AND ARROW QUESTION

THE BOW AND ARROW QUESTION