Written by Dr Mike Goldsmith

Illustrated by Andrew Pinder

Edited by Sue McMillan and Elizabeth Scoggins

Designed by Barbara Ward

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Buster Books,

an imprint of Michael OMara Books Limited,

9 Lion Yard, Tremadoc Road, London SW4 7NQ

www.busterbooks.co.uk

Copyright Buster Books 2012

Cover designed by Angie Allison

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publishers, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-907151-80-4 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78055-092-3 in EPub format

ISBN: 978-1-78055-093-0 in Mobipocket format

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Do fractions frustrate you? Do numbers drive you nuts? Never fear, this book will take you on a whirlwind tour through the fascinating world of maths, until youre potty for percentages and think decimals are divine!

Its not just about the mechanics of maths though. There are sections in this book about how maths affects all kinds of things, from the way animals behave, to the way you hear music. Lots of the greatest thinkers throughout history loved maths, and used it to invent cool stuff, and discover new things.

Whether it helps you tackle your homework, or teaches you some new facts to freak out your friends, this book will make you a maths-lover, too guaranteed.

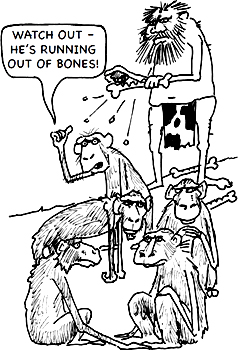

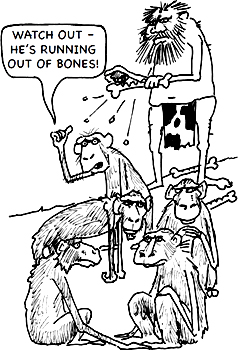

Long before calculators and computers were invented, if humans wanted to keep a record of things they had counted, they cut lines into sticks or bones. One of the earliest known examples of this kind of counting was discovered in a cave in South Africa. It was a baboon bone with 29 lines scratched into it. Tests show that the scratches were made about 35,000 years ago.

Tally-Ho!

These lines, or tallies, may have been used to count anything from animals to people or passing days.

At first, the only number symbol used was 1. Really these were just scratches on bones though, so, if humans wanted to count to 1,000, they would have had to find a load of baboon bones and scratch 1,000 1s.

Today, there are 10 different digits, or numerals 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9. These digits make up what is called the decimal system from the Latin word for ten: decimus.

The decimal system is a very logical way for humans to count most people first learn about numbers when they start to count on their ten fingers. In fact, the word digit also means finger. Its probably how you learned to count and its probably just how ancient humans started, too.

Count Like An Egyptian

The earliest known counting system based on the number 10 was used 5,000 years ago, in Egypt. The Egyptians used sets of lines for numbers up to nine. They looked something like this:

Their new symbol for 10 was  , and larger numbers used combinations of

, and larger numbers used combinations of  s and

s and  s. So 22 was written:

s. So 22 was written:

. For 100 they used

. For 100 they used  and for 1,000

and for 1,000  , up to a million:

, up to a million:  .

.

A million seemed so massive to the Ancient Egyptians that it also meant any enormous number.

Timeless Numerals

The Romans also counted in tens, using letters for numbers: I (1), V (5), X (10), L (50) and C (100). Later, D (500) and M (1,000) were added.

To write a number, letters were grouped together, and added up, or taken away, according to the order. For example, if 1 is placed in front of a letter representing a larger number, it means one less than. IX is 9, or one less than ten. The symbols CL were used to write 150 or 100 plus 50. So added together the letters CCLVII stand for 257.

You can see Roman numerals on some clocks or at the end of some TV programmes, to show when they were made.

People had been using counting systems for centuries before they realized that something was missing zero! Although an Ancient Greek man named Ptolemy did experiment with it, zero wasnt used regularly until the late 9th century.

Count Me In

Without zero, there is no way of telling the difference between, say, 166, 1,066 and 166,000. It is also a handy starting point for everything from stopwatches to rulers and temperature scales, too.

To tell the difference, a new counting system of positional notation was developed, using the place value of numbers. This system divides numbers into columns, starting with ones, or units, on the right, with tens to the left, then 100s, then 1,000s, and so on. For example, with the number 3,975, you can easily see that there are three 1,000s, nine 100s, seven 10s and five 1s.

Next page

, and larger numbers used combinations of

, and larger numbers used combinations of  s and

s and  and for 1,000

and for 1,000  , up to a million:

, up to a million:  .

.