First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Michael OMara Books Limited 2012

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84317-873-6 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-84317-921-4 in EPub format

ISBN: 978-1-84317-922-1 in Mobipocket format

Designed and typeset by www.glensaville.com

Illustrations by Aubrey Smith

www.mombooks.com

Introduction

Theres no hiding from mathematics. Its a subject so rich and diverse that we use it to explain everything from the Big Bang to how to improve your chances in a game show. Maths too plays an integral role in everyday life. You might work in a technical profession that demands frequent number-crunching, or you might only have to perform calculations when youre working out your accounts or comparing special offers on the Internet.

Maths is drummed into us from a young age. You have most likely received some degree of education in mathematics, probably up until the age of sixteen. You will have been taught arithmetic how to perform calculations; geometry, which helps us to understand shape and space; and algebra, which allows us to solve problems without having to resort to trial and error.

You may be one of an increasing number of people who has studied mathematics to degree level, or beyond. In which case you may be familiar with calculus, complex numbers, mechanics, statistics, decision mathematics or any myriad mathematical field that exists.

Whatever level of mathematics you have so far reached, it is unlikely you have ever been told much of its back story. Who decided we should work in tens? Why are there 360 degrees in a circle? Who invented algebra? Every aspect of mathematics, from the numbers we use to the way modern mathematicians tackle the big unanswered problems, is the product of thousands of years of human endeavour that goes largely unmentioned in maths lessons and textbooks around the world.

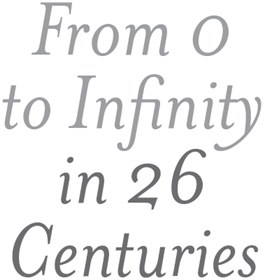

From 0 to Infinity in 26 Centuries sheds light on the fascinating history of mathematics, starting with the earliest people and working forwards to the modern day. Its a chronicle of people and their cultures; their beliefs and aims. Why does the Mayan calendar end in 2012? Why were there no notable Roman mathematicians, and yet so many in Ancient Greece? When did scientists start using maths to develop theories?

I hope that you will find the stories that follow interesting, touching and entertaining. I hope too that it will help you find a new respect for mathematics and for the people that helped to develop it into the wonderful subject that it is today.

Prehistoric Maths

B ACK TO THE B EGINNING

It has been estimated that the earliest humans arose in Africa approximately 250,000 years ago. These people left behind little evidence of their existence other than a few fossils, so we know very little about their culture, if indeed they had one.

So, what can we say about their mathematical abilities?

Early estimates

A trait that all humans and indeed primates and some other animals have is the ability to subitize: to know at a glance how much a small number of things amounts to. Here is an example:

lll

If you have the ability to subitize, you will be able to look quickly at the lines above and spot that there are three of them, without having to count each line. Now try this one:

lllllllllllllllllllllll

There are twenty-three lines here, but I only know that because I typed them. At a glance, the best you would probably be able to do is to say that there are around twenty or two dozen lines. The instantly recognizable and countable pips on a die are a modern-day example of subitizing.

We think that subitizing is a trait that has evolved in animals to allow them to make quick decisions with regard to fight-or-flight-type situations: one or two wild dogs and you might be happy to stand your ground (as long as theres a stick nearby that you can use to fend them off); three or more dogs and youre likely to run to the nearest tree.

You and I are literate and numerate humans who cant remember what it was like not to be able to count. We see three lines and we cannot help but think of the number three. Our first ancestors, however, would have had no word for three and, perhaps more significantly, possibly no concept of three as a number.

T HE S TONE A GE

Approximately 200,000 (notice the comma to help you subitize all those zeros!) years after they first walked this earth, humans gained what anthropologists call behavioural modernity: they started doing things that differentiated them from other animals. They developed language, tools, cooking, make-believe, painting, and had begun to ponder the nature of existence and all the other things that make us human. These were the Stone Age hunter-gatherers. We know a touch more about their mathematics because the remains of cavemen types were unearthed from the nineteenth century onwards and written about by their pith-helmeted discoverers.

A counting controversy

The Ishango bone is the thighbone of a baboon that was discovered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Africa in 1960. Dated at approximately 20,000 years old, the bone has caused much controversy among scientists. The bone has three sets of grooves carved deliberately into it, and if you count the grooves you find the following sequences: (9, 19, 21, 11), (19, 17, 13, 11) and (7, 5, 5, 10, 8, 4, 6, 3). Some scientists believe that this is evidence not only of the Stone Age peoples ability to count up to numbers much higher than the more recent Aboriginal tribes (well, higher than three anyway; see box below), but that the numbers in each set shows evidence of an understanding of counting in tens, odd numbers and prime numbers. This argument has been challenged by other scientists who suggest the grooves were either decorative or intended to make the smooth bone easier to grip, and therefore mathematically meaningless.

Modern-Day Hunter-Gatherer Tribes

The Pirah tribe lives today in the Amazon rainforest. They are consummate experts at jungle survival. The tribes language is so simple that its hunters use a whistled version of it while out trailing game. Remarkably (at least to us), their language contains no numbers and, despite trading commodities such as T-shirts, metal knives and alcohol with other tribes and river traders, the Pirah show no inclination to adopt a number system either. These people live in such a way that numbers have no function for them they live hand to mouth in the equatorial rainforest, where food is available all year round.

Australian Aboriginal tribes were living in a hunter-gatherer society when they were first encountered during the eighteenth century. The tribes that possessed a concept of numbers generally had words for one, two and sometimes three. Any numbers larger than three they made by adding together a combination of the first three numbers. So a tribe with words for one, two and three would have been able to count to nine by saying: one, two, three, three-one, three-two, three-three, three-three-one, three-three-two, three-three-three. The fact that these people had no word for numbers larger than three suggests that they very rarely, if ever, needed to use them.

Next page