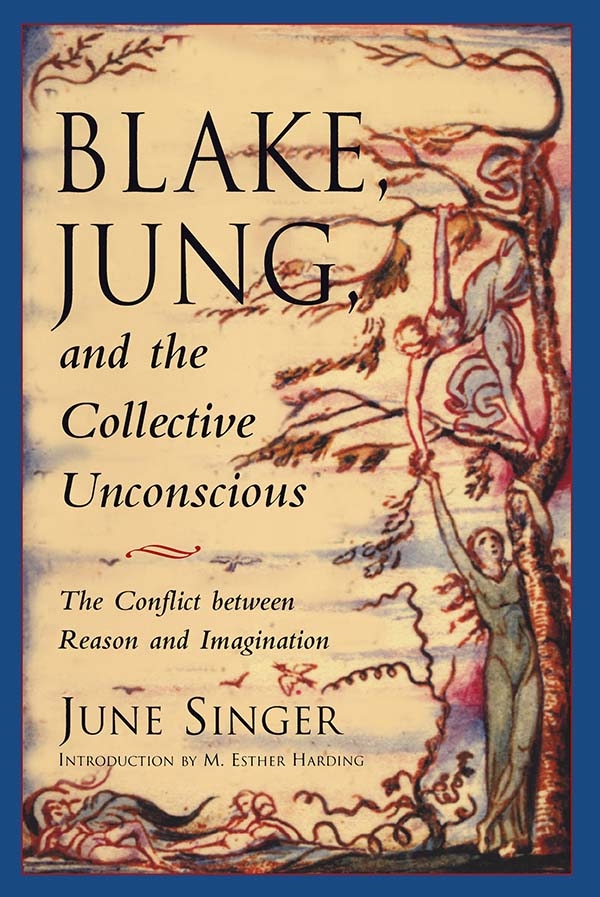

BLAKE, JUNG,

and the

Collective Unconscious

The Jung on the Hudson Book Series was instituted by the New York Center for Jungian Studies in 1997. This ongoing series is designed to present books that will be of interest to individuals of all fields, as well as mental health professionals, who are interested in exploring the relevance of the psychology and ideas of C. G. Jung to their personal lives and professional activities.

For more information about this series and the New York Center for Jungian Studies contact: Aryeh Maidenbaum, Ph.D., New York Center for Jungian Studies, 41 Park Avenue, Suite ID, New York, NY 10016, telephone (212) 689-8238, fax (212) 889-7634.

For more information about becoming part of this series contact: Betty Lundsted, Nicolas-Hays, P. O. Box 2039, York Beach, ME 03910-2039, telephone (207) 363-4393 ext. 12, email: nhi@weiserbooks.com.

BLAKE,

JUNG,

and the

Collective Unconscious

The Conflict between

Reason and Imagination

JUNE SINGER

INTRODUCTION BY M. ESTHER HARDING

First published in 2000 by

NICOLAS-HAYS

P.O. Box 2039

York Beach, ME 03910-2039

Distributed to the trade by

SAMUEL WEISER, INC.

Box 612

York Beach, ME 03910

Copyright 1986, 2000 June Singer

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Samuel Weiser, Inc. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Singer, June.

[Unholy Bible]

Blake, Jung & the collective unconscious : the conflict between reason and imagination / Jung Singer : introduction by Ester Harding,

p. cm.

Originally published: The unholy Bible. New York: G. P. Putnams Sons, 1970. With new intro.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-89254-051-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Blake, William, 1757-1827KnowledgePsychology. 2. Psychology in literature. 3. Jung, C. G. (Carl Gustav), 1875-1961Views on literature. 4. Archetype (Psychology) in literature. 5. PoetryPsychological aspects. 6. Subconsciousness in literature. 7. Imagination in literature. 8. Reason in literature. I. Title: Blake, Jung, and the collective unconscious. II. Title.

PR4148.P8 S5 2000

BJ

Cover design by Kathryn Sky-Peck

Typeset in New Baskerville 10/12

Printed in United States of America

07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992 (R1997).

In loving memory of Judith and Michael

He who binds to himself a joy

Doth the winged life destroy;

But he who kisses the joy as it flies

Lives in Eternitys sun rise.

In childhood the individual psyche is given form and shape by parents, teachers, our peer groups, and church, synagogue or mosque. We are told at every turn how we are supposed to behave, what is expected of us, and what will bring us success in the world and in the world to come. What we learn from these external influences may have little to do with what we might have learned by paying closer attention to the voices and visions that arise out of our inmost selves. William Blake, poet, painter and printer (by his own unique method) had little regard for ordinary received knowledge. He took his pleasure in the fields of imagination, where angels danced in perfect freedom and the Guardians of the Law were often bound by their own chains.

C. G. Jung, as a child, found as many ways as he could to avoid the daily grind of school, and instead immersed himself in the myths and legends of antiquity, and in building cities in the sand. He would have been an archeologist or anthropologist when he grew up, but for the need to learn a profession that would enable him to marry and support a family. Medical school held little excitement for him until he discovered the field of psychiatrywhere he could treat people who were called insane and try to draw some sense out of their nonsense. For both men, the imagination was the quality that made people human. Imagination was the sine qua non for living the creative life.

Jung asserted that while human beings live in the everyday world, we are not entirely of that world, but are connected by the slender filament of the symbol to a world beyond, which he calls the collective unconscious. Unlike Jung, Blake did not theorizehe shaped myths and symbols to express his worldview. Jung examined the statements of his patients and the symbol-rich literature of the world with an eye to finding out how the individual could become his or her most creative self. Blake had the temerity to gaze directly into the abyss and call forth its contents, which he then embellished with vivid images for all to see.

Blake had been my favorite poet ever since my mother read me his poem Infant Joy, when I couldnt have been more than 3 years old. Later, in the course of my personal analysis, when I was breaking with the collective pressures that had limited me in the past, Blakes words that had the greatest significance for me were:

I must create my own system, or be enslaved by another mans

I will not reason and compare, my business is to create.

Create I didthe gods helping. The initial impetus for my study of Blake in relation to the psychology of Jung was the requirement to write a thesis for my analysts diploma at the C. G. Jung Institute in Zurich. Blake was on my mind for weeks. I read everything on him that I could find, though my sources were limited to what I could find among the somewhat dusty volumes at the English Library in Zurich. I found every book fascinating, as each revealed some hidden aspect of the man about whose personal life so little was known.

One night I woke up at about two oclock and reached for the yellow lined pad I used to record my dreams. I wrote and wrote while the clock at Rmerhof struck the quarter hours and then three. The outline of my thesis slowly took shape under my pen. Exhausted, I finally finished, put down my pen, and fell back to sleep. In the morning, when I awoke, I half expected to find the paper blank, as if Id dreamed it all. But miracle of miracles, it was there in language so clear that all I had to do was type it just as it was! I presented it as a proposal for my thesis and it was accepted. I wrote on Blakes long poem, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the problem of contraries, and the final resolution of the problem of opposites being the papers major focus: Without contraries there is no progression. This principle has also been a leitmotif throughout Jungs works. All the time I was writing, it was as though Blake stood at my right shoulder and Jung at my left. I was not bound by the strictures of literary criticism, nor by adherence to historical fact. The guiding figure was Divine Imagination, and I allowed myself to be led by It through the Blakean labyrinth.

Next page