Contents

Guide

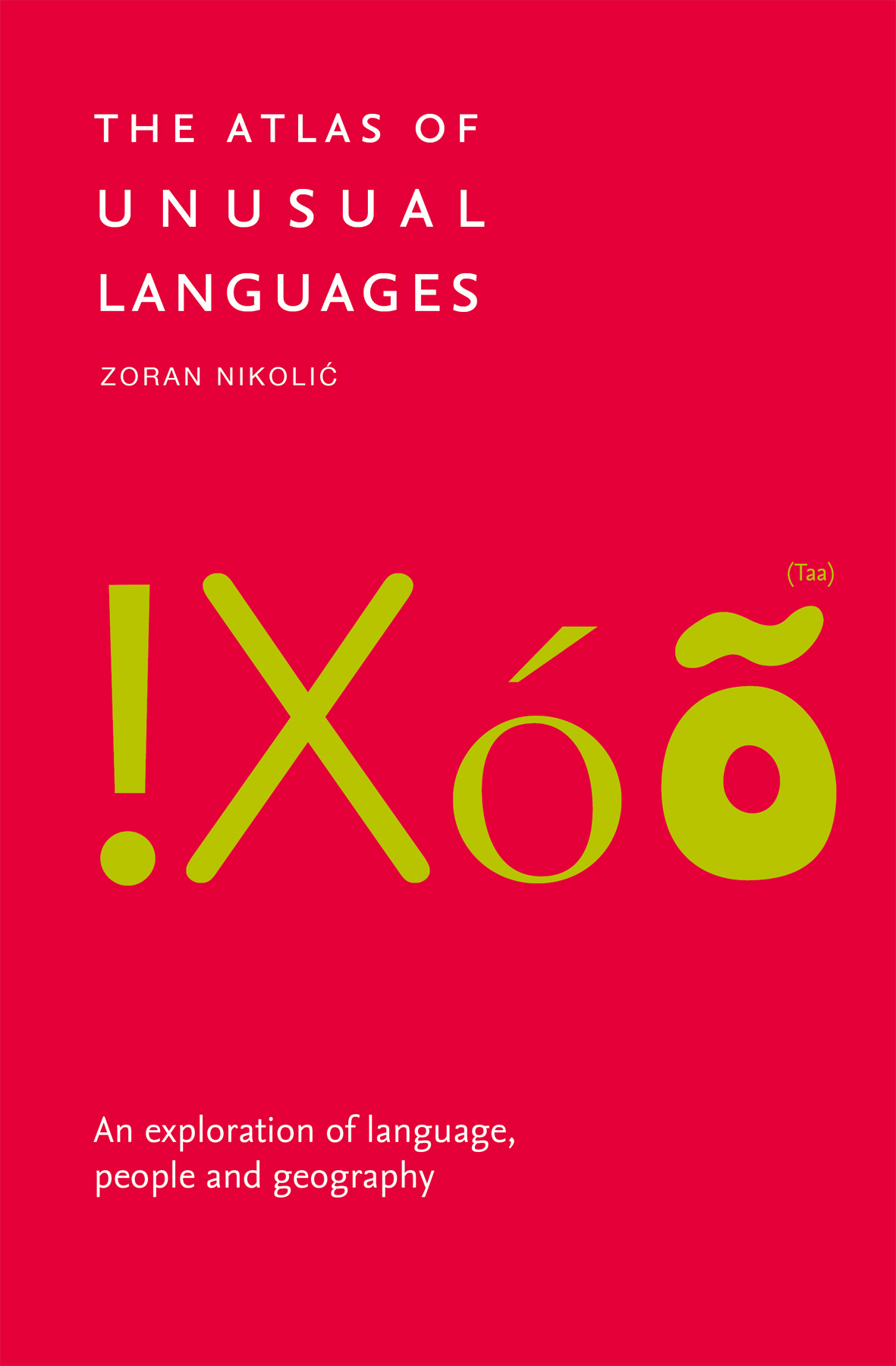

Published by Collins

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

Westerhill Road

Bishopbriggs

Glasgow G64 2QT

HarperCollins Publishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road, Dublin 4, Ireland

collins.co.uk

First published 2021

HarperCollins Publishers 2021

Text Zoran Nikoli 2021

Photographs and text credits see

Maps Collins Bartholomew Ltd 2021

Collins is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

All rights reserved under International Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

The contents of this publication are believed correct at the time of printing. Nevertheless the Publisher can accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, changes in the detail given or for any expense or loss thereby caused.

HarperCollins does not warrant that any website mentioned in this title will be provided uninterrupted, that any website will be error free, that defects will be corrected, or that the website or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or bugs. For full terms and conditions please refer to the site terms provided on the website.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All mapping in this atlas is generated from Collins Bartholomew digital databases.

Collins Bartholomew, the UKs leading independent geographical information supplier, can provide a digital, custom, and premium mapping service to a variety of markets.

e-mail:

or visit our website at: collinsbartholomew.com

eBook Edition October 2021

Source ISBN 9780008469597

eBook ISBN 9780008524043

Version: 2021-09-29

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008524043

CONTENTS

by Ivana Perii, professor of Serbian language and literature

Language is essential to our way of life. The need to convey our thoughts and feelings to each other, and to share information, has existed throughout the history of humankind. We do not know at what point people first started using the spoken word, but what began as gestures and simple sounds has evolved over time into a multitude of highly developed languages.

Throughout human history, people have moved from one area to another, perhaps searching for fertile land or in response to other factors such as conflict, climate change or religion. This migration has led to the creation of nations, the redrawing of borders and the mixing of people and therefore of the languages they speak. As a result, it is rare for a language to remain pure, staying in its original form without the influence of other tongues. The constant need for people to understand one another and express themselves has meant that languages have changed over time, which in turn has led to the creation of new languages and the extinction of others. Today, languages are disappearing much more quickly than new ones are being created.

There are an estimated 7,000 languages in use across the world today. Of these, English is the most widely spoken. The number of speakers a language has is the main factor affecting its survival. Those languages with a high number of speakers, such as Russian, Chinese and Hindi, tend to remain intact within their homelands. However, with the development of technology, they too are being affected by external influences. For a language to survive, it must adapt while at the same time keeping its individual features and serving a purpose. Even some languages regarded as dead, such as Latin, ancient Greek, ancient Slavic and Coptic, live on in some way, because we use them in literature, science, law and religion.

The status of a language within a particular country can change with each generation. Some countries have more than one official language. The Republic of Ireland, for instance, has Irish as its first official language and English as its second, but it is only Irish that is written into the constitution as the national language, even though it now has fewer speakers. In Germany, languages such as Turkish, Serbian and Greek, which have been brought into the country by immigrants, may not have the same official status as the German language, but they are being increasingly included on official government websites. While members of a minority population of a country may use both their mother tongue and the language of the country in which they live, the very concept of a mother tongue becomes less meaningful when children are raised bilingual or even trilingual without one of the languages being clearly dominant.

This book illustrates the fascinating and complex relationship between people, language and geography. How is it that in some areas, a language is spoken that is almost completely incomprehensible to other inhabitants of the same country? Why do some languages change, and what determines how long these changes last? You will find the answers within these pages. You will also discover new facts, some of which may challenge your understanding of the connection between language and place.

The author has set out to enhance your knowledge of languages in a clear and interesting way. And so, dear reader, sit back, absorb and enjoy this selection of unusual languages.

We all know what an island is: a body of land, smaller than a continent, that is surrounded by water on all sides. This water can be a river, a lake, a sea or an ocean. This definition is quite clear and unambiguous.

But what is a language island? Following the logic of the island definition, we could say that a language island is a territory where a particular language is spoken, and which is surrounded by one or more significantly larger languages. This is a conditional definition, which will, more or less, be used throughout this book.

At this point it is essential to understand the difference between language and dialect. These terms can be more difficult to define, since some linguists may view two dialects as two separate languages, while a large number of their colleagues might argue that they are two completely independent, albeit close, languages. Politics can complicate matters too, whereby one country may appropriate the language of a neighbouring country, with the aim of increasing its size and prestige. However, this is usually of little interest to the linguist, so for the purposes of this book, the following simple scenario can be used to differentiate between language and dialect:

- We have person A and person B.

- Person A knows only language A and has never been in contact with speakers of language B.

- Person B knows only language B and has never been in contact with speakers of language A.

- If person A and person B each speak their own language and understand each other well, then languages A and B are actually dialects.

Next page