RESCUING SOCRATES

RESCUING SOCRATES

HOW THE GREAT BOOKS CHANGED MY LIFE AND WHY THEY MATTER FOR A NEW GENERATION

ROOSEVELT MONTS

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-200392

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-224381

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Peter Dougherty and Alena Chekanov

Production Editorial: Brigitte Pelner

Jacket Design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Alyssa Sanford (US) and Carmen Jimenez (UK)

Copyeditor: Patricia Fogarty

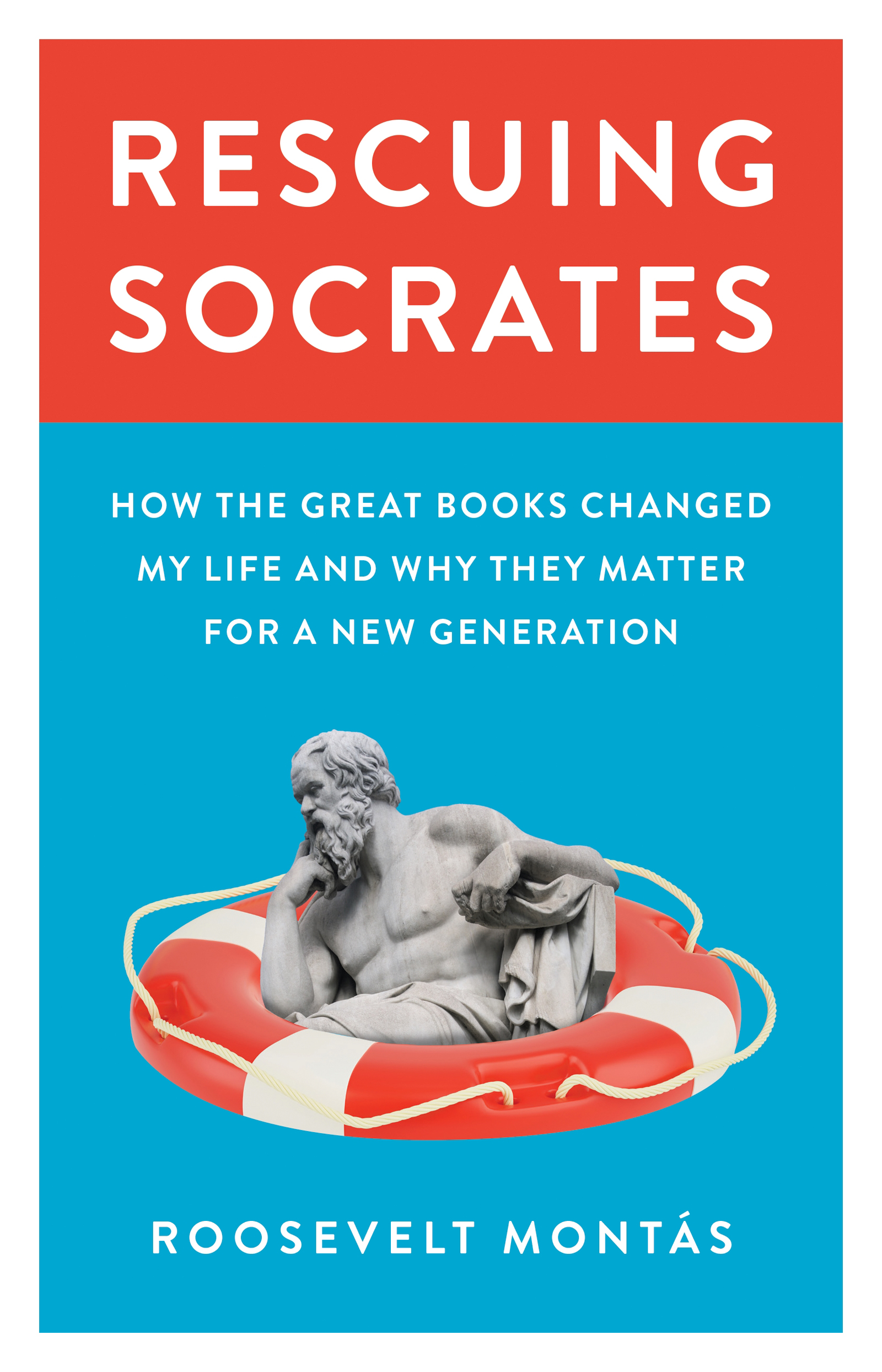

Jacket Images: (1) Life PreserverShutterstock, (2) Statue of Socrates at the Academy of Athens, built by Leonidas Drossis (d. 1880)

To Leigh and Arjunahome

CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

The Case - CHAPTER 1

Turning My Attention Back to Myself: Saint Augustine - CHAPTER 2

The Examined Life: Socrates, Plato, and a Little Bit of Aristotle - CHAPTER 3

Making Peace with the Unconscious: Freud - CHAPTER 4

Truth Is God: Gandhi - EPILOGUE

Nuts and Bolts

RESCUING SOCRATES

INTRODUCTION

The Case

This book is about my liberal education. It is also about the practice of liberal education in todays university. It is both a personal and a polemical book. Because my thinking about education is inseparable from my particular experience, this book is a meditation on how liberal education has shaped my own life. My arguments and observations draw on my career as a college professor and academic administrator, but the driving force behind this book is the way in which liberal education has altered and enriched the trajectory of my life.

That trajectory began in 1973 in Cambita Garabitos, a rural town in the Dominican Republic that was still immersed in the agrarian and pre-industrial rhythms of the nineteenth century. On May 26, 1985, I left Cambita for New York. The flight was only three and half hours long, but the distance I traveled on that day was in many ways incalculable. And it was again a long distance from learning English as a second language in the overcrowded classrooms of IS 61 in Corona, Queens, to enrolling as a freshman at Columbia University in 1991. I eventually earned a PhD from Columbia and have been teaching humanities there for twenty years. My liberal education has given me a way of making sense of this complicated trajectory.

The idea of liberal education goes back to the ancient democracy of Athens, where it was conceived as the education appropriate for free citizens. Aristotle described it as an education given not because it is useful or necessary but because it is noble and suitable for a free person. All Athenian citizens, the sort of free persons Aristotle had in mind, participated in government by voting directly on the adoption of laws, holding political office, deliberating on juries, and serving in the army. The point of liberal education was to prepare citizens for these civic responsibilities. To this day, democracies depend on a citizenry capable of discharging the duties for which a liberal education prepared Athenian citizens. Indeed, the possibility of democracy hinges on the success or failure of liberal education.

But the term liberal education, like its cousin the liberal arts, is not well understood even among academics. Outside academia, it gets a cold reception, combining the political baggage of the word liberal with the reputed uselessness of studying art. One recent critic warned that putting the words liberal and arts together is a branding disaster. Common substitutes, in part because of their innocuousness, include general education, core competencies, transferable skills, or even simply the humanities. But these alternatives fail to convey the central feature of a liberal education: its concern with the condition of human freedom and self-determination.

In the slave democracy of Athens, liberal education was distinguished from the education of an enslaved person or of a vulgar craftsman. Today, it is distinguished from professional, technical, or vocational education. Liberal education looks to the meaning of a human life beyond the requirements of subsistenceinstead of asking how to make a living, liberal education asks what living is for. These studies, says Aristotle, are undertaken for their own sake, whereas those relating to work are necessary and for the sake of things other than themselves. Liberal education concerns the human yearning to go beyond questions of survival to questions of existence.

In American colleges and universities, liberal education is typically offered as required courses, often in the humanities and social sciences, that lie outside of the students major. With some exceptions, especially in recent years,

o o o

My liberal education began with my fathers Marxist-inspired opposition to the Dominican strongman Joaqun Balaguer in the 1970s, and the political tradition through which he justified his activism. Some of his political activity took place in the opendebates and public denunciations, strikes and demonstrations, fundraising and organizing. Some of it was clandestinesecret meetings, training in guerrilla tactics, sheltering individuals sought by the authorities, establishing relations with militant leftists throughout Latin America. Although he had only a sixth-grade education, his politics were steeped in an intellectual tradition of which he was only vaguely aware, but which I began to internalize along with my first intimations of who I was in the world.

But my formal liberal education began when I entered Columbia University as a freshman and came across its celebrated Core Curriculum. Sometimes described as a Great Books program, the Core Curriculum is a set of courses in literary and philosophical classicsas well as art, music, and sciencein which all students study and discuss a prescribed list of works that begins in antiquity and moves chronologically to the present. The Core, as it is commonly known, constitutes the distinctive backbone of the education offered by Columbia College, Columbia Universitys residential liberal arts college. Legendary for its rigor, the Core is a kind of intellectual baptism that goes back more than a century and harkens to a time when an introduction to the Western tradition of learning was recognized as a self-evident good.

Today, Columbias Core Curriculum stands as a kind of relic, with no other major university requiring a common course of study in what used to be called the classics. Many schools do continue to offer liberal education through the common study of important books, but usually on an elective basis. After earning a PhD in English, my first faculty job was as a Lecturer in the Columbia Core Curriculum, and I then served as its chief administrator from 2008 to 2018.