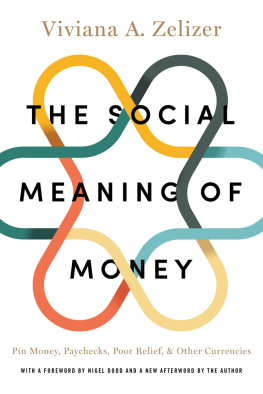

THE

SOCIAL MEANING

OF MONEY

THE

SOCIAL

MEANING

OF

MONEY

VIVIANA A. ZELIZER

With a foreword by Nigel Dodd

and a new afterword by the author

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Foreword and afterword to the new Princeton paperback edition

2017 by Princeton University Press

Copyright 1997 Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton Univeristy Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

Some material from this book has previously appeared in: The Social Meaning of Money: Special Monies, American Journal of Sociology 95 (September 1989): 342-77; Money, in the Encyclopdia of Sociology, ed. Edgar F. Borgatta and Marie L. Borgatta (New York: Macmillian, 1992), pp. 1304-10; and Making Multiple Monies, in Explorations in Economic Sociology, ed. Richard Swedberg (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1993), pp. 193-212.

All Rights Reserved

press.princeton.edu

eISBN: 978-0-691-23700-8

R0

For Julian, my dear son

FOREWORD TO THE 2017 EDITION

V iviana Zelizers The Social Meaning of Money has become a sociological classic. It is a book to place alongside Simmels The Philosophy of Money as an analysis of the money form that is not so much of its time, as ahead of its time. Just as Simmel might be said to have anticipated the emergence of circulation and exchange, as opposed to production labor, as the key organizing principles of economic life in late capitalist societies in the second half of the twentieth century, so Zelizer seems to have foreseen the explosion of monetary forms that has marked the first two decades of the twenty-first century as so interesting and significant for scholars and other observers of money.

Zelizers analysis has altered the very language that sociologists use to describe money: earmarking is a striking and original way of depicting how we draw qualitative differences between various amounts of somethingmoneythat classically gets viewed as homogenous. Using a rich variety of historical examples, the book amply illustrates that not all dollars are the same. Indeed we see in many ways that something that scholars have conventionally portrayed as colourless and blandand therefore as meaningless and detached from social relations, and even as damaging for themis shaped by and for social life in endlessly interesting ways. What emerges from this analysis is an idea that is among the most far-reaching of the book: multiple monies.

There was always an intriguing tension in this book between what might be called the phenomenological and the ontological dimensions of Zelizers argumentthe first dealing mainly with how money is seen, the second with what it is. We can see this by distinguishing between three interpretations of the earmarking idea as it gets used in the pages of this book. The first refers explicitly to the meanings that we give to money without fundamentally altering its objective character. This is to take a micro as opposed to a macro approach to the analysis of currency, to view money from below, not from above: from the perspective of moneys users, not its producers. The second involves showing how social practices modify money by restricting its use, regulating its allocation, or modifying its appearance. The third version of the earmarking idea is the most radical, because it concerns not just the marking but the actual production of money through the creation of entire new currencies, such as local currencies or Bitcoins, and the transformation of various objectssuch as cigarettes or chewing guminto monetary media.

I am not suggesting that there is any conflict or ambiguity between these interpretations; indeed I think that they are closely interrelated and sometimes overlap. Each gives out to a rich set of possibilities for researching the social production and exchange of money in the contemporary world. It is a major strength of The Social Meaning of Money that its core organizing conceptearmarkingoffers such a productive array of potential avenues for research. Having said this, the third interpretation of earmarking underlines the true significance of Zelizers book for understanding money in our age. Increasingly, we inhabit a world of monetary pluralism. Multiple monies as Zelizer describes them do not just refer to the varied meanings we give to our money, the different uses we put it to, and the qualitative distinctions we make in order to differentiate specific amounts of it. Multiple monies surround us: in the choices we have between different kinds of currency (international, national, local, corporate, crytographic), different payment systems (PayPal, Apple Pay, iZettle), and different monetary media (cash, plastic, digital) in our everyday lives.

Nobody is suggesting that monetary pluralism is absolutely new: if anything, it is a case of back to the future, a return to a situation in which several currencies circulate side by side. And in many countries, monetary pluralism was a basic fact of life throughout the modern era. But with the emergence of new payment systems, digital currencies such as Bitcoin, and in the resurgence of local monies and social currencies, we are witnessing a new wave of monetary pluralism. The remarkable thing about The Social Meaning of Money is that it leaves us very well equipped, conceptually, to navigate this renewed complexity of the worlds monetary landscape. This is the true meaning of the conversation the author has with Simmels ghost in the closing section. Money will not simply disenchant the world, because we will keep coining new names, as well as defining new uses and designating separate users, for our multiple currencies. The world has, one might say, caught up with this great book. This is the true measure of its significance, and why it so thoroughly deserves to be called a true sociological classic.

Nigel Dodd, LSE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C OMPRESSING GRATITUDE into a judicious inventory of help received, favors bestowed, and obligations accumulated makes a complex array of personal ties one-dimensional. It misses the rich distinctions among varieties of gratitudes, the multiple and very particular sorts of advice, encouragement, and understanding received from different individuals and organizations in the long process of writing a book.

Let me try to describe my many gratitudes. As he has for the past two decades, Bernard Barber listened to my ideas, read each draft, and advised me in this project from its very start. With infinite generosity, Charles Tilly provided indispensable commentaries at critical points. Michael B. Katzs work on American welfare history offered an important guide for my research on changing relief policies, as did his thoughtful comments. I thank other friends and colleagues who gave varied and valuable suggestions: Jeffrey C. Alexander, Sigmund Diamond, Paul DiMaggio, Susan Gal, Albert O. Hirschman, Jenna Weissman Joselit, David J. Rothman, Ewa Morawska, Loc Wacquant, and Eviatar Zerubavel.

In the past few years I discussed sections of this book in many university seminars, working groups, and conferences. For helpful comments, I am grateful to members of the Russell Sage Seminar in Economic Sociology, Princeton Universitys Department of Sociology Workshop in Economic Sociology, the Princeton Society of Fellows of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, Pierre Bourdieus seminar at the cole Des Hautes tudes en Sciences Sociales, and the National Humanities Centers conference on The Gift and Its Transformations, as well as to attentive audiences at the University of Chicago, Columbia University, the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Harvard University, the New School For Social Research, New York University, the University of Pennsylvania, Yale University, and the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University.