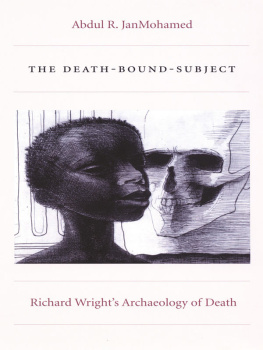

Abdul R. JanMohamed - The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions)

Here you can read online Abdul R. JanMohamed - The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2005, publisher: Duke University Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions)

- Author:

- Publisher:Duke University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2005

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Series Editors: Stanley Fish and Fredric Jameson

Duke University Press Durham and London 2005

2005 Duke University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

Designed by C. H. Westmoreland

Typeset in Carter and Cohn Galliard by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book.

For Ayesha

The research for this study of Wright was conducted, at its earliest stages, with the generous aid of a fellowship from the University of California Humanities Research Institute at the University of California, Irvine (for a collaborative research project on Minority Discourse), and in its final stages with the support of fellowships from the American Council of Learned Societies, the University of California Presidents Fellowship in the Humanities, and a Humanities Research Fellowship from the University of California, Berkeley. I am deeply grateful to all of them for providing me the time to complete my work.

I remain forever grateful to my colleaguesPal Ahlu-walia, Maria Bates, Marcial Gonzalez, Saidiya Hartman, George Lipsitz, Kenny Mostern, and John Carols Rowefor reading portions of the manuscript at various stages of revision and providing encouragement, criticism, and fruitful suggestions. I would particularly like to thank Donna Przybylowicz, who has lived with this project on death for many years and who has enlivened it; Mitch Breitweiser, whose unfailing support and prolonged and incisive conversation about this and many other projects and topics have been absolutely invaluable; and Ruth Jennison and Kimberly Tsau, whose assistance in the research process and in various stages of preparing the manuscript proved invaluable. Finally, I would like to thank Ken Wissoker, Pam Morrison, and the staff at Duke University Press for expertly guiding the manuscript through the production process.

Singing love songs to Mr. Death, they smashed his head. More than the rest, they killed the flirt whom folks called Life for leading them on. Making them think the next sunrise would be worth it; that another stroke of time would do it at last. Only when she was dead would they be safe. The successful onesthe ones who had been there enough years to have maimed, mutilated, maybe even buried herkept watch over the others who were still in her cock-teasing hug, caring and looking forward, remembering and looking back.TONI MORRISON, Beloved

For it is not enough to decide on the basis of its effectDeath. It still remains to be decided which death, that which is brought by life or that which brings life.

JACQUES LACAN, crits

You are either alive and proud or you are dead, and when you are dead, you cant care anyway. And your method of death can itself be a politicizing thing So if you can overcome the personal fear of death, which is a highly irrational thing, you know, then you are on your way. They just killed somebody in jaila friend of mineabout ten days before I was arrested. Now it would have been bloody useful evidence for them to assault me. At least it would have indicated what kind of possibilities were there, leading to this guys death.STEVE BIKO, I Write What I Like

Introduction

THE CULTURE OF SOCIAL-DEATH

Richard Wrights first published short story, Big Boy Leaves Home, consists of a rite of initiation in which the protagonist, generically named Big Boy, reaches his manhood by being forced to witness the shooting of two of his friends and the slow, gruesome lynching of another. In Wrights last published novel, The Long Dream, which revisits the same scene (the parallelism of which will be explored in detail in ), a similar initiation requires Fishbelly, the young protagonist of this bildungsroman, to reach his manhood also by watching a lynching, less gruesome, but no doubt more traumatic: not only is he forced by the white chief of police to watch his father, who has been shot by the police, bleed to death slowly, but he is also prevented from summoning medical help, thereby being compelled to share the guilt of his fathers death. In between these two fictional events, Wright complainsat about the age of eleven, when, after a very traumatic childhood, he is caught up in the frenzied white riots and numerous lynchings in the South that followed the First World Warthat, though I had never in my life been abused by whites,I had already become as conditioned to their existence as though I had been the victim of a thousand lynchings (Black Boy, 72). Though all the evidence available to us strongly suggests that Wright was a gentle, loving man, the evidence is equally clear that his fiction is replete with gruesome, deathly violence: lynching, murder, and violent struggles to the death are the leitmotifs that tie his novels and short stories together into a coherent body of work. Wright was clearly obsessed with death and lynching. For instance, his first three fictional works, a collection of five short stories and two novels, contain a total of twenty violent, gruesome deaths, including those of all but two of the protagonists. Though critics have commented on the ubiquitousness of violence in Wrights work, it is curious that no one has yet fully articulated the fundamental ideological and political functions of death in his work and life.

This is understandable to some extent: death is an eventuality that none of us want to examine too closely; it immediately, universally, and perhaps automatically provokes disavowal of one sort or another. But, if we are willing and able to bracket our fears and anxieties about death and look closely at its political valences and functions in Wrights fiction, something remarkable is revealed. I hope to demonstrate by the end of this study that Wright conducted, partly through a series of conscious and deliberate decisions, but partly through extremely sharp intuitive, often unconscious choices, a systematic and thorough archaeology of what I will call the death-bound-subject, that is, of the subject who is formed, from infancy on, by the imminent and ubiquitous threat of death. The death-bound-subject is a deeply aporetic structure to the extent that he is bound, and hence produced as a subject, by the process of unbinding. The processes through which that aporetic subject is produced by the threat of death constitute the fundamental object of this study. Put in their simplest forms, the cardinal questions posed in the rest of this book are the following: What happens to the life of a subject who grows up under the threat of death, a threat that is constant yet unpredictable? How does that threat permeate the subjects life? How far and how finely does death penetrate into the capillary structures of subjectivity (considered here as a psychopolitical construct)? And, finally, once death has percolated into the innermost reaches of subjectivity, what kinds of effects does it have, and how does it manifest it self eventually in the comportment, attitudes, and actions of the death-bound-subject? Though Wright never fully articulated the questions in this manner, I hope to demonstrate that they furnish the underlying teleological structure of his work.

I will be arguing that Wrights pursuit of these questions was unconsciously tenacious to the point of obsession and that each of his fictional works excavates progressively deeper layers of the same site, that on which the formation of the death-bound-subject took place. And what Wrights archaeology of death unearths is neither idiosyncratic nor, ultimately, eccentric; it is, indeed, extreme, but not eccentric. Because it throws everything into stark relief, it is the kind of extremity that better allows us to comprehend the normal effects of the threat of death on the formation of subjectivity. And, because it can do this, it opens up a door to the critical understanding of a much larger formation and tradition. My work on Wright has convinced me that there exists a powerful, if somewhat submerged, tradition within African American literature and culture that continually and systematically meditates on the effectivity of the threat of death as a mode of coercion. I say somewhat submerged because the traditions existencefrom the earliest slave narratives (Equianos reporting of slaves being buried alive, Douglasss classic battle with Covey, and Jacobss equally classic form of resisting slavery by a prolonged sequestering of herself in her grandmothers garret, a space roughly twice the size of a coffin, where she almost dies several times), to the powerful contemporary re-evaluations and renewed articulations (a remarkable cluster of feminist novels such as

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions)»

Look at similar books to The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Death-Bound-Subject (Post-Contemporary Interventions) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.