RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Jing Tsu

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Script and character illustrations by Naiqian Wang and Stephanie Winarto.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tsu, Jing, author.

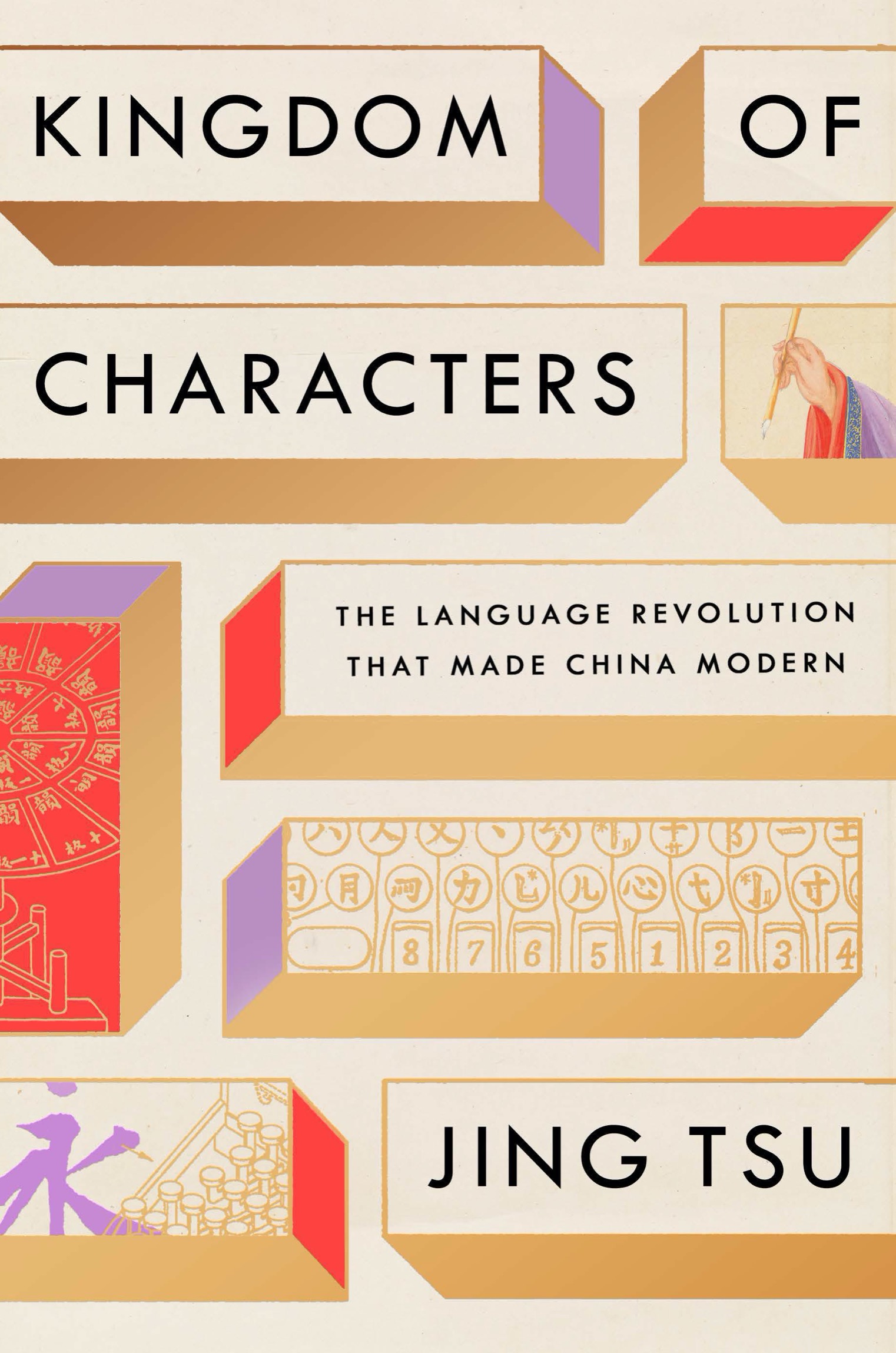

Title: Kingdom of characters : the language revolution that made China modern / Jing Tsu.

Description: New York : Riverhead, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021017006 (print) | LCCN 2021017007 (ebook) | ISBN 9780735214729 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780735214743 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese charactersHistory20th century. | Chinese languageWritingHistory20th century. | Chinese languageModern Chinese, 1919

Classification: LCC PL1171 .T776 2022 (print) | LCC PL1171 (ebook) | DDC 495.11/1dc23/eng/20211110

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021017006

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021017007

Book design by Meighan Cavanaugh, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

pid_prh_6.0_138931607_c0_r0

To David

contents

Evolutionary theory says that the inferior shall be gotten rid of.... We must then start with the Chinese script.

Li Shizeng (1907)

If the Chinese script does not go, China will certainly perish!

Lu Xun (1936)

Computers are finally able to process Chinese! Long live square characters!

Chen Mingyuan (1980)

Introduction

Few contemporary societies take their writing culture as seriously as China. The oldest living language spoken by the most people, at the same time ancient and modern, Chinese is currently used by more than 1.3 billion peoplenot counting those around the globe who learn it as a second language. Its written form has remained largely unchanged since it was first standardized more than 2,200 years ago. By comparison, the number of letters in the Roman alphabet fluctuated until the sixteenth century, when the letter j split from i and completed the twenty-six-letter set.

Chinese heads of state are probably the only political leaders in the world who can still be seen demonstrating their cultural prowess at official occasions, in their case by dashing off a few characters or auspicious phrases with an ink brush. Deng Xiaoping was reputedly a bit shy, but his immediate predecessor and onetime rival, Hua Guofeng, devoted his late life to the practice, and former president Hu Jintao was fond of displaying his penmanship in public. Maos calligraphy still sits prominently on the masthead of the countrys official newspaper, the Peoples Daily, and recent computerized handwriting analysis showed that Xi Jinpings style is remarkably similar. Such showmanship not only serves as a daily reminder of the leaders legitimacy but also reinforces the importance of a cultivated skill that has been the hallmark of Chinas ruling elite since the time long before nations. Calligraphy, in fact, is one of the few practices of the Chinese tradition that survived the countrys twentieth-century revolt against its feudalistic past.

Its hard to imagine an American president or European head of state opening an official state ceremony or visit with a show of penmanship. But in the Chinese context, literacy means something more than just knowing how to read and write. It has traditionally signaled many things: the mark of being steeped in the classics and wisdom of the ancients; a meditative craft through which to cultivate a higher self; an elite medium through which to express ones inner character, thoughts, and emotions.

Deciphering Chinese is not only an insiders art; it has also been a cross-continental pursuit. For more than four centuries, devoted followers of the Chinese language in the West have tried to peer into the secrets behind its ideographic capture of reality, speculating about its provenance and complex physical structure. Extravagant claims and theories met with enthusiastic reception in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe and twentieth-century America. Kings, clerics, adventurers, scholars, modern poets, and theorists of language were drawn to its strangeness and exceptionality, looking for a key to unlock its secrets through grammar and compositional laws. Sixteenth-century Jesuit missionaries labored to learn it, seventeenth-century savants were fascinated by it, and eighteenth-century Sinologists fetishized it.

How an entire civilization outside of Christendom evolved to have a writing system as complex and massive as the Chinese script has been an enduring linguistic mystery for outsiders. This inquiry poorly masks a deep suspicion: How can a people who read and write in characters ever think the way we do? Even in the late twentieth century, views like this were touted by Western experts in different fields. Alphabetic thinking, social theorists would say, explains the advent of the scientific revolution in the West. A modern theorist of networks and the digital age sees the alphabet as a conceptual technology that forms the bedrock of Western science and technology. A scholar of ancient Greece saw the signs much earlier at the fount of Western civilization, where the alphabetic mind was responsible for all the Wests accomplishments. Joseph Needham, a renowned British historian of Chinese science, spent his lifes work defending scientific inventions in ancient China against claims like these, but he also recognized that the Chinese language remained the greatest barrier for Westerners to understanding the minds of the Chinese. It is Chinas first and last Great Wall.

The Opium War of 1839 to 1842 marked the beginning of a new course for China. During a series of crises and confrontations with the Western world that would keep China in an inferior position well into the early years of the twenty-first century, the demise of the Chinese script was foretold by many. Still, the Chinese were hesitant to accept the prospect of a future without their written language. They saw how the Chinese language, like the empire, might not be viable in a modern world increasingly transformed by various branches of Western science and new modes of electricity-powered communication, beginning with the telegraph. But the Chinese language had been the fundamental building block of Chinas cultural universe. So rooted was the script in the countrys history and institutions over the millennia that it was difficult for the Chinese to consider abandoning it. From the grassroots to the highest level of the modern state, intellectuals, teachers, engineers, everyday citizens, eccentric inventors, duty-bound librarians, and language reformers embarked on one of the most extraordinary revolutions of the millennium in search of a solution. That is the subject of this book. The rude awakening of Western cannons firing at the gates; a teetering empire and the last throes of the imperialistic order; an urgency to modernize taken into overdrive by a new political ethosall these shifts compelled the Chinese to embark on a parallel course: to get their language on the same footing as languages using the Western alphabet.