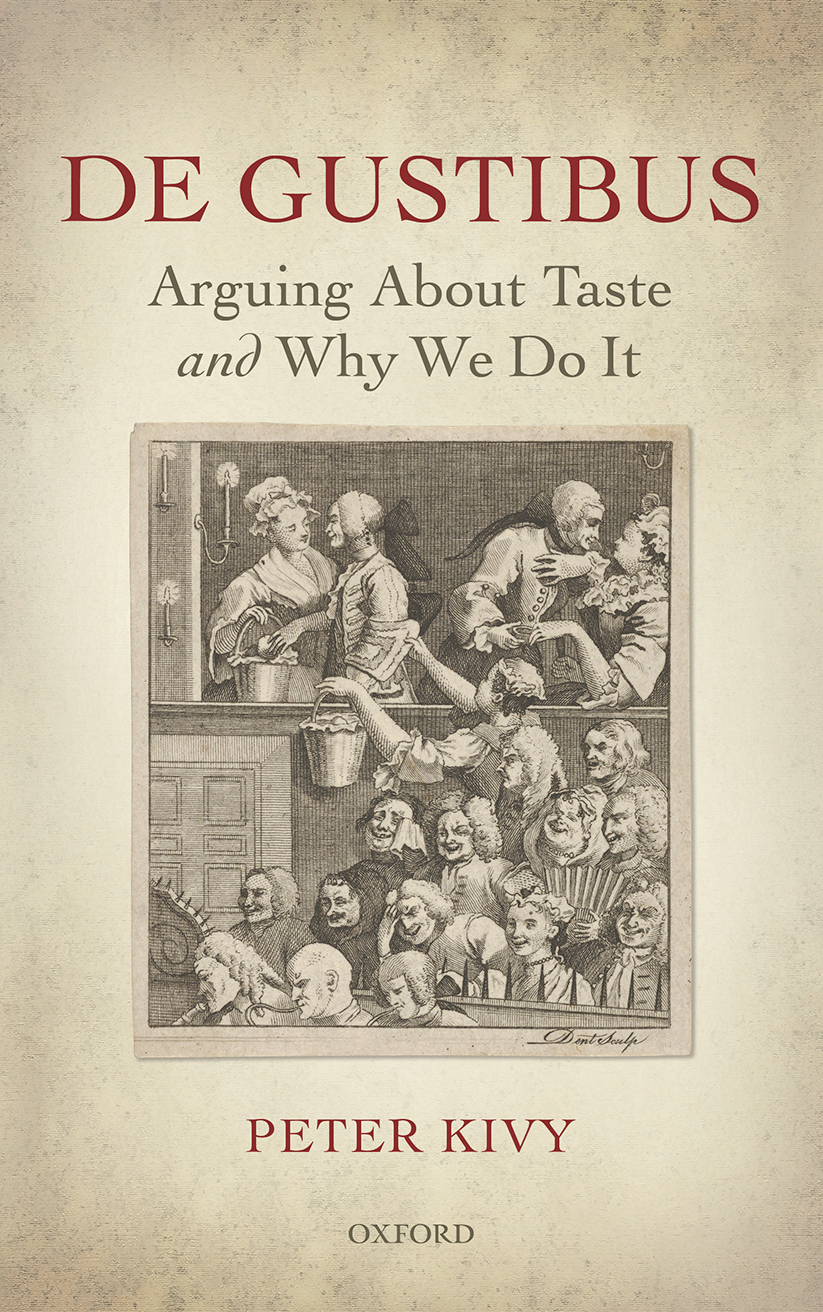

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

The seed from which this monograph sprouted was planted some thirty odd years ago1980, to be precisein an essay of mine called A Failure of Aesthetic Emotivism, Philosophical Studies, 38 (1980), pp. 35165, portions of which, now in revised form, are included here in with kind permission of Springer Science+Business Media.

I do not at present really recall how the idea for this article came to me. For at the time, the so-called emotive theory of ethics was dead as the Dodo bird, and why I should have been thinking about it at all I cannot imagine. Be that as it may, the point I made in that essay was that contrary to what might, on first reflection, be thought, the emotive theory of ethics was more plausible in at least one respect than was the emotive theory of aesthetics, namely, it provided a plausible explanation for why we engage in ethical disputes, whereas the latter provided none for why we engage in aesthetic disputes, disputes over taste, which manifestly we do.

Furthermore, I was even emboldened, in that essay, to suggest that, again contrary to what one might initially conjecture, aesthetic realism might, in the event, be a more defensible position than ethical realism. But there I essentially let the matter drop; and although in 1992 I went over much of the same ground again in an invited essay for the Library of Living Philosophers volume devoted to A. J. Ayer, I got no further with it, and the whole thing quietly slipped my mind.

But whereas I do not now recall why I became concerned with the emotive theory of value in the first place, in 1980, I know quite well what reminded me of it not very long ago, and what led me to the writing of the present monograph. I was invited, in 2012, to comment on a paper of James Harolds, at the Pacific Division meeting of the American Society for Aesthetics. In that insightful presentation, Professor Harold proposed the hypothesis that what is sometimes called these days expressivism in ethics, the view that ethical value terms such as right, good, and just, do not refer to facts about the world but express attitudes towards it, is true of aesthetic value terms such as beautiful and sublime as well. And he then went on to explore the question of how ethical attitudes and aesthetic attitudes might differ from one another.

Needless to say, ethical and aesthetic expressivism are the present day offspring of the old emotive theory of value. So in reading, and in framing my comments on Harolds paper I was naturally put in mind of my previous forays into ethical and aesthetic emotivism. As well, I ventured to suggest that the case was the same with ethical versus aesthetic expressivism as with ethical versus aesthetic emotivism, namely, expressivism worked better for ethics than for aesthetics, and for the same reason. Ethical expressivism could provide a plausible motive for engaging in ethical disputes, but aesthetic expressivism could not do so for aesthetic disputes. And I concluded my comments on Harolds paper by suggesting, as I had done previously in my discussion of aesthetic emotivism, that aesthetic realism, not aesthetic expressivism, could indeed provide the motive for aesthetic disputation.

But, more importantly, the thoughts that Harolds paper engendered in me did not end there. For I was now beginning to realize that the whole issue of why we engage in aesthetic disputes, in disputes over taste, which manifestly we do, was relatively unexplored territory in philosophy of art. And it is that territory that I then resolved to explore.

We are, indisputably, disputatious animals. Our lives are filled with episodes in which we attempt to bring others round to our way of thinking, and they us to theirs. We seem compelled, as it were, to seek from others acquiescence in our beliefs or our attitudes. And we engage in disputation, in argument, as well as in other forms of persuasion, to bring agreement about.

Sometimes it is obvious why someone would wish to persuade someone else of his belief, or bring her around to share his attitude. Sometimes, however, it is not. And it is my contention here that it is not obvious why we should wish to persuade others to share what I shall call, broadly speaking, our aesthetic beliefs or attitudes. But, furthermore, it seems clear to me that, nevertheless, we do so wish, as is made quite evident by the widespread existence, both past and present, of vigorous, persistent, and on occasion heated aesthetic disputation among commentators on the arts as well as among the general public. Thus it appears to me we are faced with a classic kind of philosophical dilemma. There seems no apparent reason why we should dispute about taste in the arts, and in beauty, yet ample evidence that we do. It is this philosophical dilemma that I wish to explore in the present book.

As with many of my other writings, this one begins with, and is deeply indebted to eighteenth-century philosophers, and particularly, Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, and Immanuel Kant. For it is in the Enlightenment that the modern discipline of aesthetics and philosophy of art begins. And the problem I am engaged with here seems to me embedded in that formative period in the discipline to such a degree that starting my discussion anywhere else would be tantamount to an act of intellectual dishonesty as well as intellectual suicide. Like so much else in contemporary philosophy, my problem begins in earnest in the early modern period. And so it is there that I will not only begin, but return to frequently as the need arises.

That being said, I will just append the caveat that the present book is not by any means meant to be an essay in the history of aesthetics and philosophy of art but, I hope, a contribution to the present state of the art.