For my mother.

INTRODUCTION

THE BORDER IS EVERYWHERE

Borders dot the perimeter of every country and are present wherever you are at any given moment, no matter how far you are from the actual line separating one nation from the next. Borders are physical places, they are imaginary lines, and they are quite often deadly. People live on borders, and people die on borders. Food crosses borders, and people starve on borders. Borders produce profits for some, and borders generate poverty and suffering for most. Borders follow those who cross them. In the airport, near points of entry, and in the backs of police vans: the border is everywhere.

I dont remember the first time I set eyes on a border, but it would have been in the late nineties, during a daytrip with my family. We crossed from Texas, where I grew up, to a town south of the Mexican border. It was when I moved to Israel and Palestine, where I worked as a reporter for four years, that I first saw a massive border wall. Known to Israelis as a security fence and to most Palestinians as an annexation wall, the mostly concrete barrier includes guard towers, barbwire, and soldiered checkpoints. Like all borders, Israels wall not only attracts violenceit is a magnet for clashes between Palestinian youth and Israeli soldiersbut is in and of itself violent. The wall encroaches on Palestinian land, divides families, and crushes livelihoods.

I was fresh from visiting and writing about communities dotting the border between Lebanon and Syria, where militias armed to the teeth geared up for a battle with the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), when I first traveled to Greece in late 2015, at the height of the mass refugee exodus from war-ravaged and economically devastated countries around the Middle East, South Asia, Africa, to Europe. During that trip, I stood on the shores of Skala Sikamineas, a village on the northern tip of the island of Lesbos. There, I stared out at the waterthe border is everywhereas emaciated dinghies carried dozens of men, women, and children crossing the choppy waters of the Aegean Sea, all of them with the hope of reaching safety. Some people wore lifejackets, some wore pool floaties, and some had nothing at all. A few days later, I flew back to mainland Greece and headed north. Outside Idomeni, a village on the Greek-Macedonian border, a tent city had popped up. Thousands of people slept in tents or under the purple skies, enduring the elements. Afghans, Iraqis, and Syrians had fled war. Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, and Moroccans had fled poverty. Bonfires blazed from nightfall onward, exhausted bodies and slack faces encircling them, sitting on the wintry earth cross-legged or with blanket-swaddled children in their laps. Smoke rose in the air, wraithlike. I heard, from every direction, hacking coughs, violent sneezing, and both loud and whispered conversations in Arabic, Farsi, French, Punjabi, Urdu, and Swahili. The rank odor of decaying garbage and molding clothing stuffed in soaked knapsacks rode the gusts of wind that swept through the camp. Whether they left home to escape bullets or empty stomachs, one young man told me, they had left home with the most universal of human desires: to live. Even as borders slammed shut across the Balkans and the rest of Europe, warehousing tens of thousands of refugees and migrants in Greece, people continued to come. SOLIDARITY WITH PEOPLE STRUGGLING IN IDOMENI , a letter tacked to a corkboard in the camp declared, AND ALL THE MIGRANTS WHO ARE BREAKING THE VIOLENT BORDERS OF EUROPE . YOU ARE NOT ALONE IN THIS STRUGGLE .

In late 2019, the number of boats reaching Greek islands from Turkey had hit the highest level since the crisis erupted more than four years earlier. In fact, around the world the number of people displaced across international boundaries had continued to soar. In 2018, the number of refugees and displaced people around the globe hit a record high when the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) documented nearly twenty-six million people seeking international protection outside their home country.

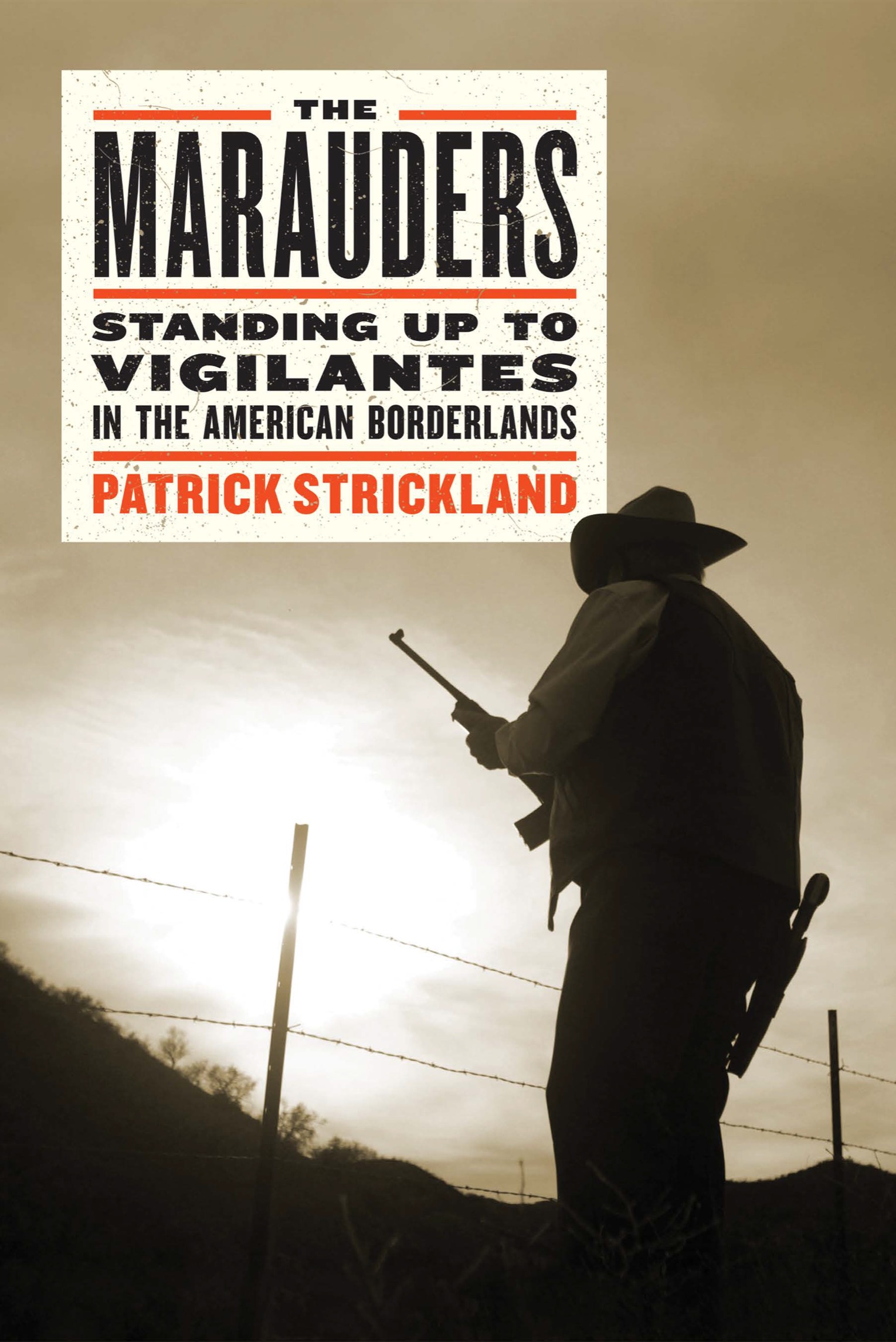

Traveling back and forth between Europe, the Middle East, and the United States between 2015 and 2020, I found myself in border communities time and again, always attempting to make sense of the hate and violence that frontiers inspired. Over the course of two years and during several visits to a handful of communities in southern Arizona, I followed the story of militias and vigilante conspiracy theorists taking up arms to keep immigrants, migrants, and refugees out of the United States. Standing up to people who trafficked in fear, conspiracy theories, and violence was no easy task, and it was one that often prompted yet more fear, conspiracy theories, and violence.

Around the world, the border is everywhere, and everywhere you go, there are idealistic dreamers envisioning a world without it. While I researched and wrote this book, I often thought back to a poster I saw in a squat in Exarchia, the central Athens neighborhood where I usually reside. When the global refugee crisis first reached Europe in 2015, I visited several squats popping up in and around the Greek capital, where anarchists and leftists had taken over abandoned buildings and repurposed them to provide safe housing for displaced people and provide an alternative to the overcrowding and decrepitude of life in the refugee camps. Throughout the last five years, Ive passed more hours than I can count in such squats, interviewing squatters and refugees, watching films and sitting in on lectures, and observing general assemblies: the process through which squat residents and volunteers make decisions on the basis of consensus. And Ive read and photographed too many posters and graffiti slogans to count, but one has stuck with me. THE BORDER IS EVERYWHERE , it read. WE WILL ATTACK THE REASON FOR OUR SUFFERING .

On the brisk morning of November 1, 2018, only a few days before the midterm elections, I sat in Al Jazeera Englishs office in Washington, DC. The border had defined much of the election season, and US president Donald Trump had turned it into the central issue. A so-called caravan of refugees and migrants, mostly from Central America, was en route to the United States, and Trump repeatedly warned the nation that this constituted a national security threat like none other: an invasion, he said. Heeding the presidents call to arms, militia groups armed to the teeth were flocking south to communities all along the border.