Andrew Ure - Philosophy of Manufactures

Here you can read online Andrew Ure - Philosophy of Manufactures full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1967, publisher: Psychology Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Philosophy of Manufactures

- Author:

- Publisher:Psychology Press

- Genre:

- Year:1967

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Philosophy of Manufactures: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Philosophy of Manufactures" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Philosophy of Manufactures — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Philosophy of Manufactures" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

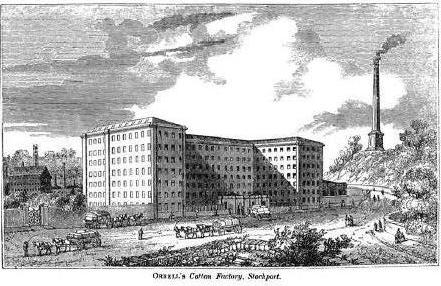

AN EXPOSITION OF THE

SCIENTIFIC, MORAL, AND COMMERCIAL ECONOMY

OF

GREAT BRITAIN

this reprint but points out that some imperfections

in the original may be apparent

S. Pharm. Soc. North Germany,

&c. &c. &c.

CHARLES KNIGHT, LUDGATE-STREET.

MDCCCXXXV.

In the wages-column of table, page 373, the figures have been printed with horizontal lines, as vulgar fractions, instead of oblique lines, as shillings and pence. It should read lls., lOs., 5s, 8d,,-'' 5d., 4s., 3s. 6d., 2s. 6d.

In the wages-column of table, page 373, the figures have been printed with horizontal lines, as vulgar fractions, instead of oblique lines, as shillings and pence. It should read lls., lOs., 5s, 8d,,-'' 5d., 4s., 3s. 6d., 2s. 6d.Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Philosophy of Manufactures»

Look at similar books to Philosophy of Manufactures. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Philosophy of Manufactures and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.