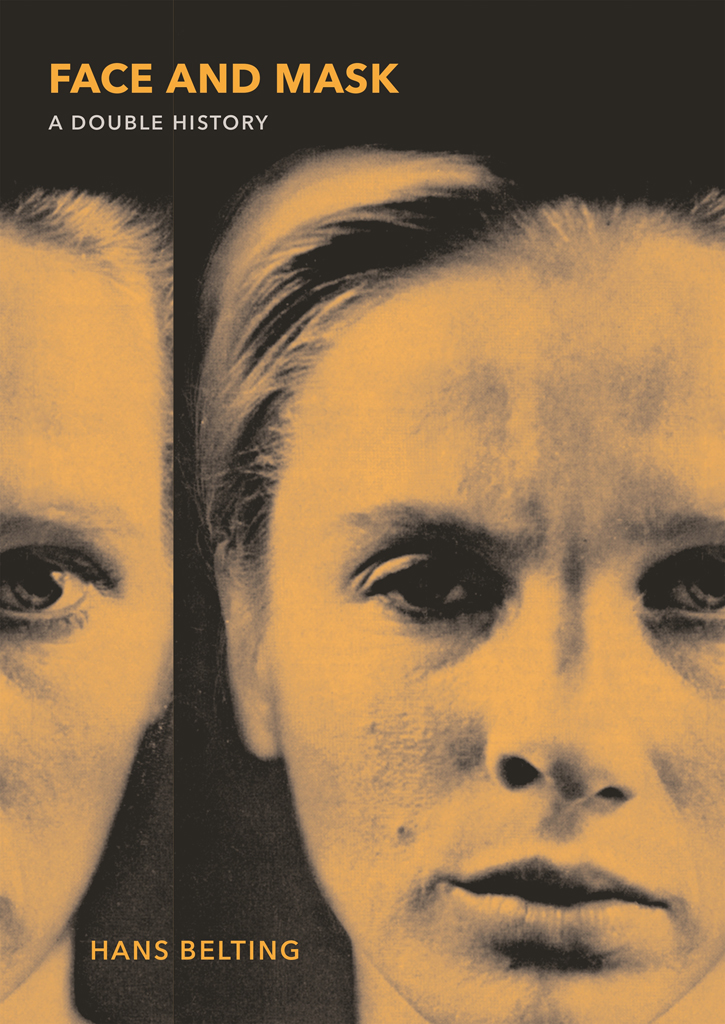

FACE AND MASK

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Princeton and Oxford

FACE AND MASK

A DOUBLE HISTORY

HANS BELTING

Translated by Thomas S. Hansen and Abby J. Hansen

First published in Germany under the title

Faces: Eine Geschichte des Gesichts

Verlag C. H. Beck oHG, Mnchen 2013

Translation copyright 2017 by Princeton

University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

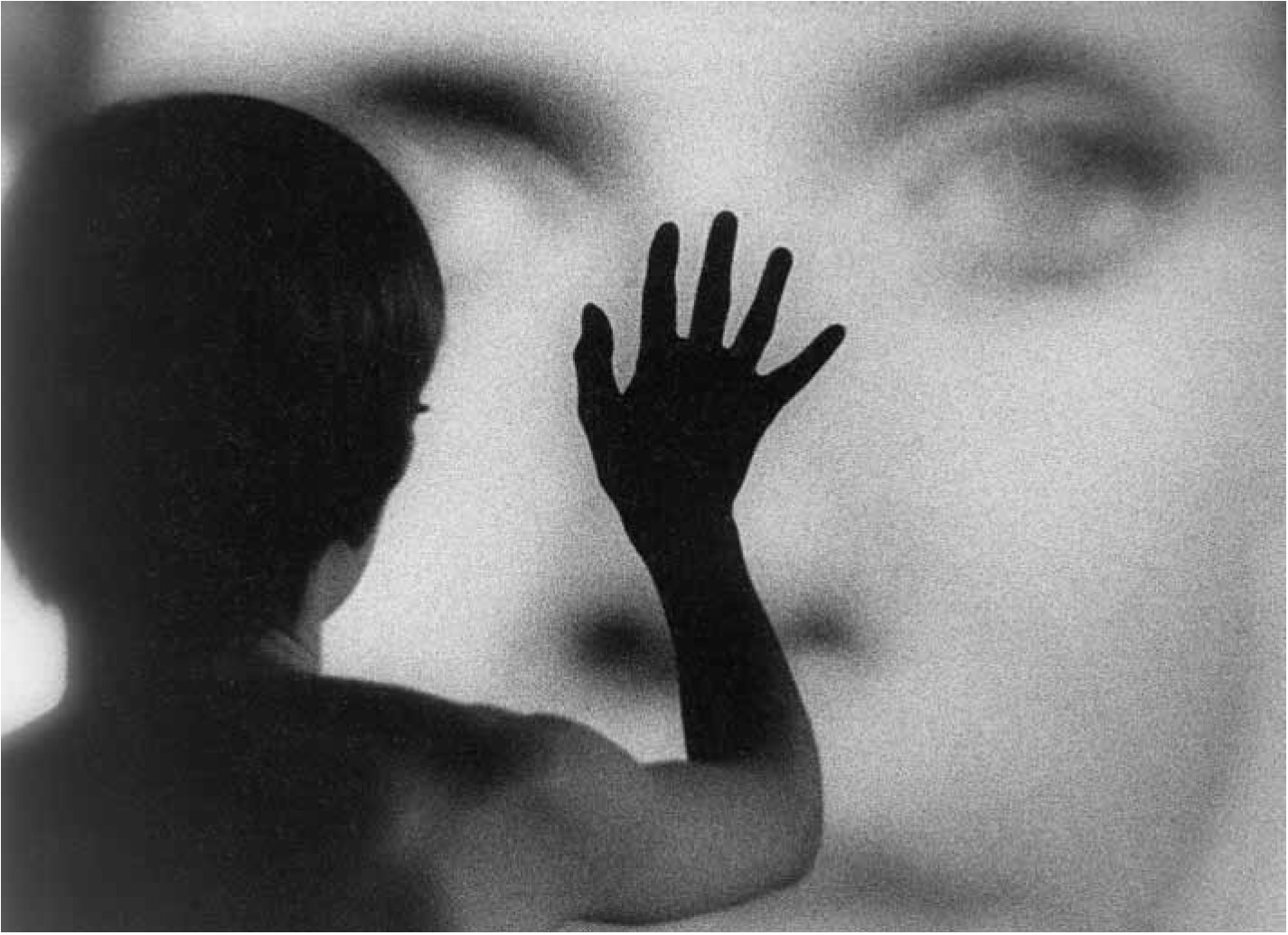

Jacket illustration: Ingmar Bergman, Persona: Collage of Two Faces, 1966 (film still and poster)

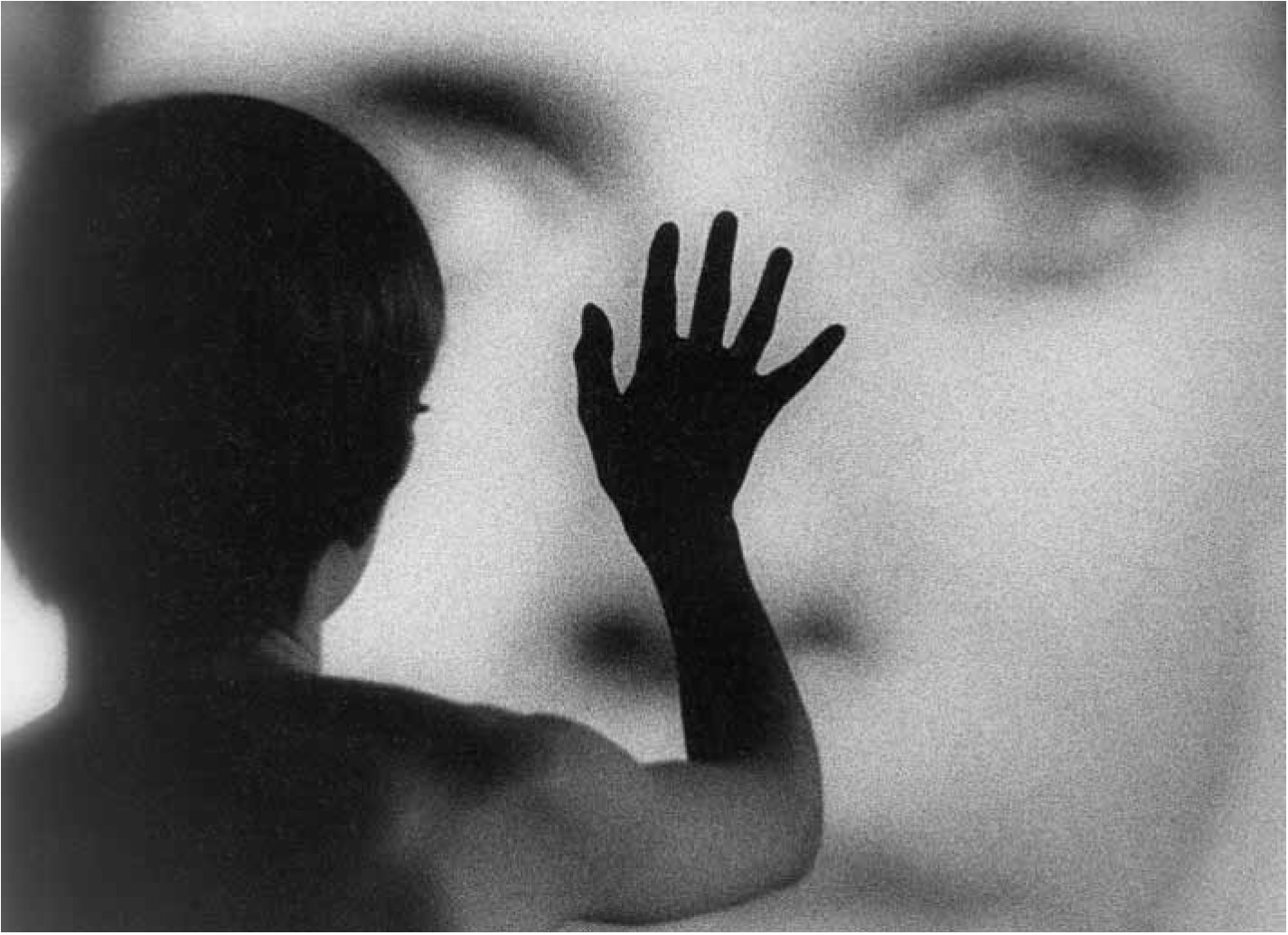

Frontispiece: Still from Ingmar Bergmans film

Persona, 1966

Front matter illustrations: pp. ivv, details of

Part opening illustrations: p. ;

p.

All Rights Reserved

Names: Belting, Hans, author. | Hansen, Thomas S.

(Thomas Stansfield), translator. | Hansen, Abby J.,

1945 translator.

Title: Face and mask : a double history / Hans Belting ; translated by Thomas S. Hansen and Abby J. Hansen.

Other titles: Faces. English

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2017. | First published in Germany under the title Faces: Eine Geschichte des Gesichts. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016021495 | ISBN

9780691162355 (hardback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Face in art. | Face. | Masks. |

Facial expression. | Facial expression in art. |

FacePsychological aspects. | MasksPsychological aspects.

Classification: LCC N7573.3 .B45813 2017 | DDC 704.9/42dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016021495

eISBN: 978-0-691-24459-4

R0

For us the most entertaining surface in the world Is that of the human face.

GEORG CHRISTOPH LICHTENBERG, SUDELBCHER, F. 88

INTRODUCTION: DEFINING THE SUBJECT

A history of the face? It is an audacious undertaking to tackle a subject that defies all categories and leads to the quintessential image with which all humans live. For what, actually, is the face? While it is the face that each of us has, it is also just one face among many. But it does not truly become a face until it interacts with other faces, seeing or being seen by them. This is evident in the expression face to face, which designates the immediate, perhaps inescapable, interaction of a reciprocal glance in a moment of truth between two human beings. But a face comes to life in the most literal sense only through gaze and voice, and so it is with the play of human facial expressions. To exaggerate a facial expression is to make a face in order to convey a feeling or address someone without using words. To put it differently, it is to portray oneself using ones own face while observing conventions that help us understand each other. Language provides many ready examples of figures of speech that derive from facial animation. The metaphors we all automatically use about facial expressions are particularly revealing. To save face or to lose face are typical of these. They speak of control or threat to the face, but each also goes to the very core of the individual one is referring to. And yet we are not always in control of our faces. Faces are tied to a lifetime during which they change and are stamped by experience. But they can also be inherited, learned by rote from another (as with mother and child), and recalled when one wishes to remember a person.

In the public sphere, by contrast, faces assume other roles, conform to conventions, or subordinate themselves to the ubiquitous official icons produced by the media. These icons dictate the faces of the majority instead of seeking true eye contact with them. One example would be an ideal of beauty generic to a period in which a preference for either plain or strong faces prevailed.

We cannot understand the face solely as an individual attribute, because it is clearly constrained by social forces. The domestication of faces in the nineteenth century is thus a historical phenomenon. To counter this development, August Sander records the upheavals in German society after World War I in a book of photographs titled Face of the Times. This brings up the problem of how to talk about a History of the Face. It is a different topic from the history of European portraiture, which began in the early modern period and encountered its first crisis with the invention of photography in the nineteenth century. What, then, does history mean in our case? What significance can it have within the framework of this book if it extends to all faces in general? Here we begin to discover a variety of possibilities for talking about a history of the face.

The life history of an individual face is familiar to everyone. That is not our topic here. A face changes with age when creases etch themselves into the sagging skin that gradually loosens from the skull; the creases become the expressive lines, wrinkles, and contours. These are what remain from the faces constant work of creating expression. They denote individual facial habits, which become fixed through a set repertoire of expressivity, and those habits are thus engraved in the face. In addition, a face can sometimes seem older or younger than the body that bears it, creating a sort of asymmetry that results from interplay during the course of a life.

Physiognomy is congenital and determined by skull structure. Yet the coherence in a face that we see after a long absence is sometimes made more obvious when we hear the voice, which recalls the face from the past even when it has changed dramatically. Even though a face remains itself during the course of a life, it does not stay the same.

The natural history of the face (as Jonathan Cole has called it) is not my subject here, although it has been highly significant regarding the expressive powers of the face. The face that we have is just as much the expression that we give it as it is the result of evolution.

Charles Darwin, who based his findings on those of Charles Bell and Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne, focuses on the idea of evolution in his The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. The consciousness for which the face developed into a living mirror was central to the development of individuality. Facial movements that humans control are partly primordial and thus reflect a prehistory, but they are also partly a product of human evolution. The more mobility and expressivity the face gained, the more refined its ability to convey feelings became.

This evolutionary process was completed before the emergence of the cultures now familiar to us. It was in these that the face first acquired those shades of meaning that expand upon nature and interpret it. Among these are faces that are painted or tattooed, groomed and styled, affective or secretive. The same is true of masks fabricated as artifacts representing faces and worn over faces. Prehistoric funerary cults invented the mask in order to replicate a lost face upon the corpse. Not until the advent of European culture and the social history of the modern era was the mask first understood not as a substitute but rather as a facsimile, a disguise and means of concealing the face. In self-representation with the real face, however, social norms have been at work, but shaped by cultural traditions. Cultures, furthermore, also differ in their interpretation of the face, but not in the same way that different races do.