2004 by the University of Washington Press

Afterword 2014 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Symonds, Patricia V., author.

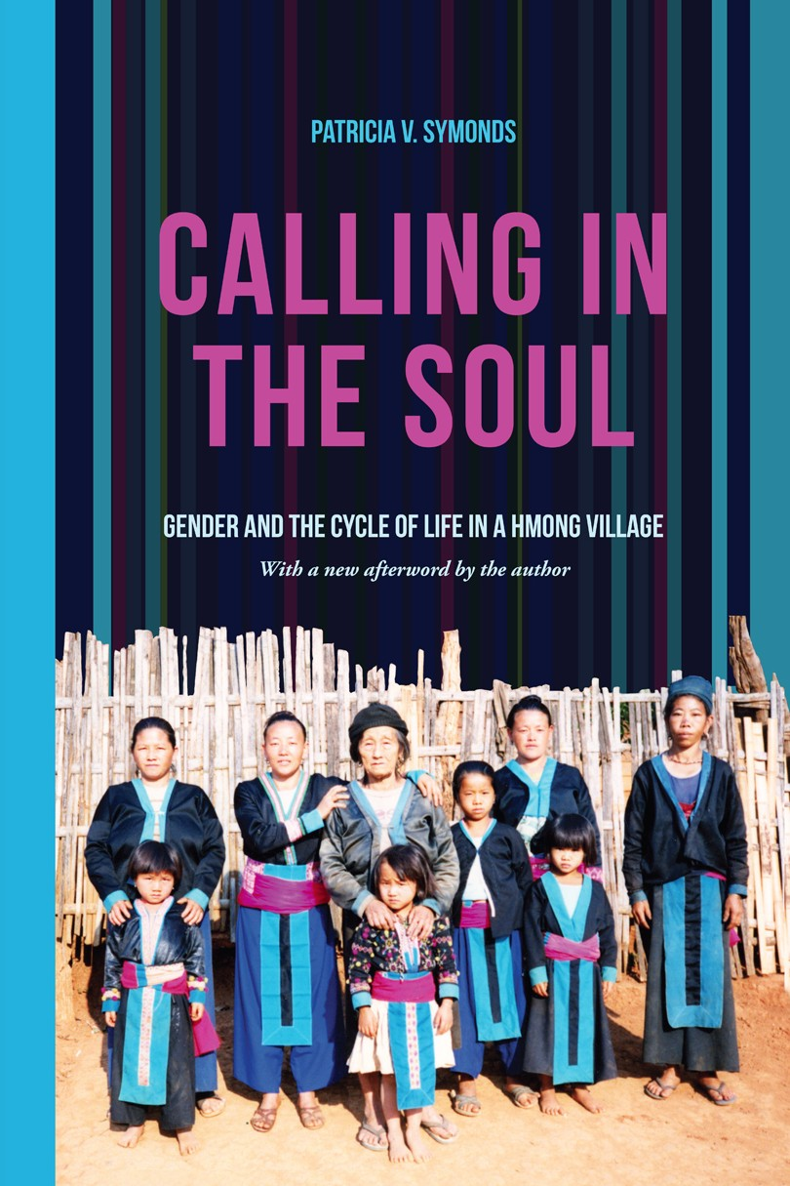

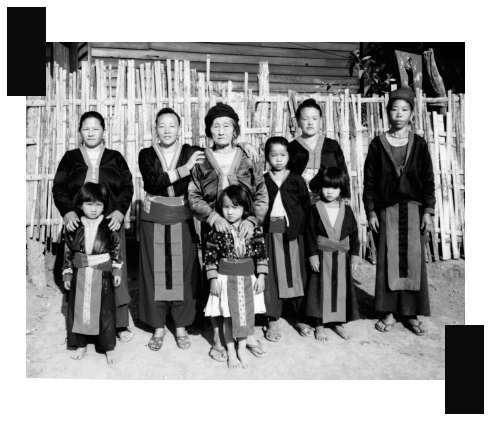

Calling in the soul : gender and the cycle of life in a Hmong village / Patricia V. Symonds; with a new afterword by the author.

pages cm.

Includes texts in Hmong with English translation.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99421-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Hmong (Asian People)Thailand, NorthernRites and ceremonies 2. Women, HmongThailand, NorthernSocial conditions. 3. Sex roleThailand, Northern. 4. Sexual division of laborThailand, Northern. 5. Patrilineal kinshipThailand, Northern. 6. Hmong AmericansSocial life and customs. 7. Thailand, NorthernSocial life and customs. I. Title.

DS570.M5S95 2014 305.8959'720593dc23 2014011541

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ISBN 978-0-295-80565-8 (electronic)

PREFACE

MY INTEREST IN HMONG birthing practices began in 1979, when I was collecting medical histories from women at a clinic for low-income patients in Providence, Rhode Island. Many of these women were Hmong refugees from the hills of Laos. Few of them spoke English, and even fewer came in for early prenatal care. They were apprehensive about the medical procedures, even those as simple as having their blood drawn or providing a urine sample. At the prospect of getting a physical examination by a male physician, they were frightened and resentful. All too often one of the health clinics Hmong clients arrived at a local hospital with her newborn baby in her arms, having given birth at home or in the car on the way to the hospital.

With only one Hmong interpreter on duty, and only in the mornings, the women did not get much individual attention, and their responses remained a mystery to me. It was only when the interpreter and I had become close friends that I began to understand why Hmong women subjected themselves to the Western medical practices they obviously mistrusted: they wanted to become eligible for the federal Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC), which provided food vouchers; and to ensure that their babies became citizens, they needed to document birth in the United States.

Later I conducted research on adolescent pregnancy and its implications

One morning, Iab Moua Yang and I visited a pregnant woman at the home of her husbands parents, where the young couple lived. We wanted to interview the couple about their marriage, but the husband was not at home. The young woman invited us to sit down, her mother-in-law offered us Coca-Cola, and the interview began. After about an hour, the young woman said that she was in labor and feeling uncomfortable. I was quite startled; she had given no indication that she was in pain. I immediately offered to take her and her mother-in-law to the local maternity hospital.

As soon as we arrived, the young woman was examined and then taken to the delivery room; meanwhile I obtained permission from both the doctor and the mother-in-law to observe the birth. When the nurse told the young woman to remove her clothing, she began to protest, but a few words from her mother-in-law made her comply with the nurses instructions to undress and don the hospital johnny. The physician conferred with Iab Moua Yang to get permission to rupture the chorionic membrane and/or to perform an episiotomy if necessary. Iab Moua Yang asked the mother-in-law, who refused permission for both procedures.

The young woman was not a participant in these discussions. If she gave any indication that she was in pain, such as moaning softly, her mother-in-law would silence her by saying that she was bringing shame upon her family. The mother-in-laws influence appeared to upset the physician, who said, The girl is afraid of the mother. If I need to carry out these procedures, I will insist she leave the room. Fortunately, the infant was born without the need for medical intervention. The fact that this young woman was able to deliver her child without expressing pain pointed to the way in which childbirth is constructed by the Hmong.

As I observed several more births in the Hmong community in Providence, I became acutely aware of the concerns of many Hmong women, especially their fears of an episiotomy or a Caesarean section. The Hmong believe that any surgical procedure disrupts the balance of the body in relation to its surroundings: that anesthesia causes soul loss; that one will never be physically or spiritually well in this world if something is taken from the body; that metal placed in the bodysuch as a pin in a bonewill prevent a person from peacefully entering the land of darkness at death; and that all of these ill effects will be borne throughout future incarnations.

I was also aware of the medical providers concerns, in particular their questions as to why Hmong women would not come to the clinic for prenatal care. The staff also wanted women to arrive at the hospital early enough in their labor that the child would be born in the hospital, but Hmong women arrived with newborn babies in their arms more and more often. Nor did the staff understand why Hmong women refused to eat hospital food or drink cold juices or water.

In 1986 I decided to undertake a study of Hmong birth practices in Southeast Asia, to understand at firsthand where these women were coming from in a literal as well as a metaphorical sense. I saw the Hmong women in Rhode Island struggling with the Western health-care system, and I hoped that if I could understand how they conceptualized and experienced childbirth, I might be able to mediate between their worldview and that of Western biomedicine. I wanted my research to help Western medical staff understand Hmong beliefs so that they would be more sensitive to the cross-cultural issues.

The uses of my initial study were not exactly as I had envisioned. By the time I returned home in 1988, many of the Hmong women I knew in Providence had learned to speak English and were becoming educated about Western medicine. The hospitals that could afford to were hiring translators, many of them Hmong, who could mediate between hospital staff and Hmong patients, so going to the hospital to give birth was not as terrifying as it had been. By the year 2000, hospitals all over the country had become sensitive to some of the Hmong health-care issues, in part due to the efforts of Hmong scholars such as Xoua Thao, Bruce Thowpaou Bliatout, Yang Dao, and Gary Yia Lee, as well as American scholars such as Peter Kunstadter, Anne Fadiman, Dwight Conquergood, Nancy Donnelly, Elizabeth Kirton, Kathleen Culhane-Pera, and others, including myself and my students. Hmong had established their own organizations to advise and educate Hmong on medical, legal, and social aspects of life in the United States. Some Hmong are now lawyers, nurses, and physicians themselves and have made a point of helping other Hmong who come to them as clients or patients. Dr. Xoua Thao, who trained in the Brown/Dartmouth Medical School and practices medicine in Minnesota, where there is a large Hmong population, is just one of these. As well, Hmong children who have been educated here are able to advise their parents and families, and to explain the sometimes confusing tenets of Western biomedicine.

![Yang - The latehomecomer: [a Hmong family memoir]](/uploads/posts/book/165016/thumbs/yang-the-latehomecomer-a-hmong-family-memoir.jpg)