2015 by the University of Washington Press

Composed in Minion Pro, a typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

Printed and bound in the United States of America

18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Turner, Sarah, 1970 author.

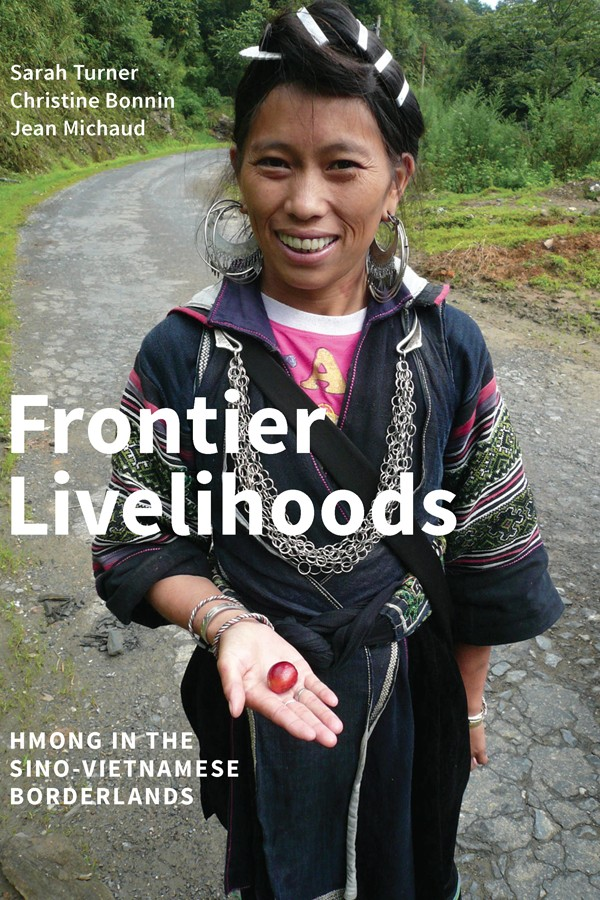

Frontier livelihoods : Hmong in the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands / Sarah Turner, Christine Bonnin, Jean Michaud.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99466-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Hmong (Asian people)ChinaYunnan Sheng. 2. Hmong (Asian people)Vietnam. 3. EthnologyChinaYunnan Sheng. 4. EthnologyVietnam. 5. BorderlandsChinaYunnan Sheng. 6. BorderlandsVietnam. I. Bonnin, Christine, 1976 author. II. Michaud, Jean, 1957 author. III. Title.

DS731.M5T87 2015

305.8959'7205135dc23

2014036407

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ISBN-13: 978-0-295-80596-2 (electronic)

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THE HIGHLANDS IN THE CHINA-VIETNAM BORDERLANDS ARE A craggy, rough, and unforgiving place. Until the eighteenth century, they contained no roads, only footpaths, and fell largely outside any local administration on either side of the border. Only those with few other options elected to live there. Increasing demographic pressures in the surrounding mid- and lowlands, combined with a near-constant state of civil war in southwest China, then uprooted populations and forced many to migrate. Those who arrived in the higher reaches of this border region in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had little choice but to attempt to make their livelihoods work in difficult environs. For a while, these inhabitants existed largely apart from surrounding empires. But soon the adjacent states came to claim these mountains too.

This area is part of the Southeast Asian Massif, a broad expanse of highlands extending southeast of the Himalayan Plateau and shared today among ten countries. James C. Scott (2009) has dramatically argued that these vast highlands represent the Last Great Enclosure. Scott has proposed that these uplands, while linked to lowlands via trade relations for generations, have in recent centuries become increasingly claimed by modern states through incorporating processes variously labeled as development, economic progress, literacy, and social integration (ibid., 4). For most local residents on the ground, this has meant the replacement of communal property with private land-use rights, the introduction of cash cropping, and a push to turn shifting cultivators into permanent farmers. The aim has been less to make upland individuals more productive than to ensure that their economic activity was legible, taxable, assessable, and confiscatable or, failing that, to replace it with forms of production that were (ibid., 5). Today, in the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands, much of this relationship between state rulers and those living in the upland fringes continues.

Still, endogenous modes of economic behavior in these borderlands remain understudied and poorly understood, let alone appreciated. For the Chinese and Vietnamese states, knowing more about specific minority upland livelihoods was, and largely still is, an unnecessary burden, slowing down the pace of national economic integration and the desirable modernization of these little brothers. The nation has a promising future; the ways of the past have to give in. In these highlands, the result is a distinctive context in which peasants are turned into labor forces, government-sponsored businesses incessantly extract valuable natural resources, and lowland economic migrants arrive looking for new economic opportunities, while state officials enforce national directives and ethnic minorities maintain livelihoods as best they can.

This situation begs numerous fundamental questions. Why, and how, do such tribal people consent to modernize? What practices are they willing to let go of, and what practices do they decide to adopt? As ethnic minorities, do they have any power left to alter the course of their fates? And if so, how? These questions have stimulated our longitudinal studies among these highland societies, and this book is an attempt to glean some answers. This social space requires much more scholarly attention than it has yet received.

The segment of the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands under study here is home to over two million people officially labeled as ethnic minorities. Many, like the Hmong, belong to kinship-based societies that are geographically dispersed as well as politically divided between countries. These high margins have long been considered by those holding political control over them as a remote frontier inhabited by inconsequential peoples who lag behind in national statistics, lack civilization, and are stuck in a state of chronic poverty. We contend, on the contrary, that these individuals and households have much to teach the rest of the world. Far from selling out and passively accepting the states project, they make do with the little they have to construct creative, adaptive, and resilient livelihoods that the state often knows little about. Theirs might be a remote place, but in our view it is far from just another fast-disappearing distant tribal corner of the world.

After two centuries of continuous presence in the Sino-Vietnamese borderlands, how does this particular, emblematic society, the Hmong, currently cope with the pressing demands to integrate into the Chinese and Vietnamese nations under heavily centralized socialist regimes and to step to the tune of the market economy? It is our contention, after two decades of observation and reflection, that Hmong livelihoods are much more complex and finely adjusted than is generally thought. Hmong individuals, households, and communities creatively blend active engagement, cautious choices, and, at times, resistance. And by resistance, we do not suggest that Hmong in these uplands refuse change. That would be a simplistic depiction. Rather, they use their agency to indigenize aspects of modernity, and they set in motion forms of adaptation that make sense to them, which sometimes amount to subtle yet perceptible acts of resistance to modernization processes.

We also want to move beyond the confines of prevailing academic research that tends to focus solely on national settings. There is an urgent need to study societies such as the Hmong translocally and transnationally, to get at the ways in which their distinctive historical and cultural features persevere despite the fractures caused by national borders and policies made in distant national centers of gravity. Country-based studies on national minorities are abundant and helpful but tell only part of the story. Given the cross-border nature of Hmong livelihoods, translocal and transnational approaches to social space are needed, with observations, ethnographies, and viewpoints from both sides of the border. By placing agency at the center of our discussions, we explore what it means for Hmong individuals and households to share an identity across adjacent countries, to be confined within the restrictive definition of a minority nationality (