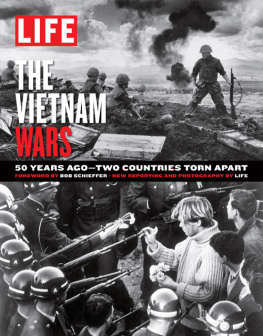

THE VIETNAM WARS

50 YEARS AGOTWO COUNTRIES TORN APART

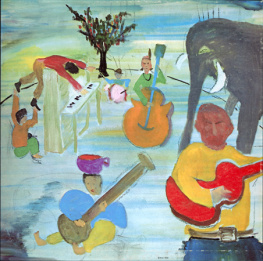

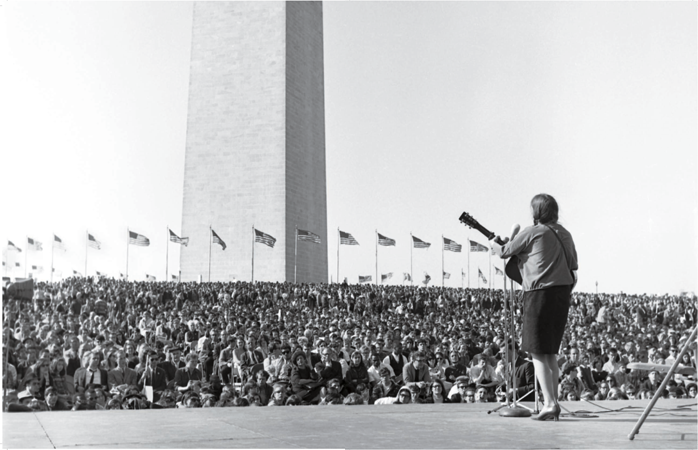

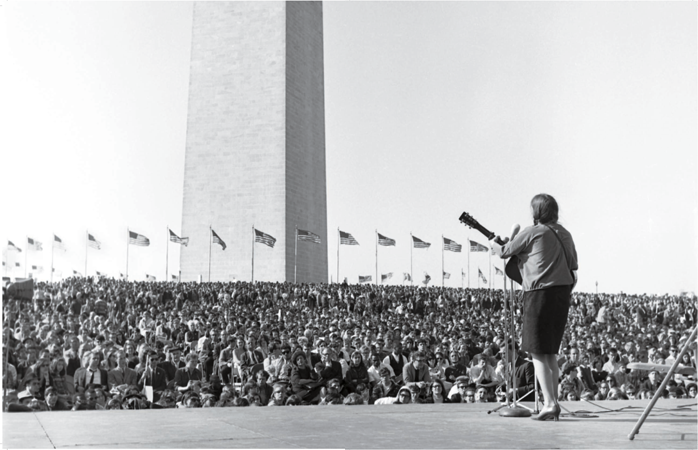

In a never-before-published photograph, Judy Collins performs at the March on Washington to End the War in Vietnam on April 17, 1965. Photograph Daniel Kramer

Larry Burrows spent nine years covering the Vietnam War. Among the many works of his included in this book is this shot of U.S. Army Captain Robert Bacon taken in 1964. Photograph by Larry Burrows Larry Burrows Collection

FOREWORD: FINDING VIETNAM

BY BOB SCHIEFFER

COURTESY BOB SCHIEFFER

SCHIEFFER then (above) and now (below).

DONNA MCWILLIAM/AP

The thing about Vietnam was always the ironies. In those days, America was the most powerful nation in the world, economically and militarily.

However, for nearly 11 years no initiativefrom the grandest nuclear arms negotiations to the smallest domestic programcould be undertaken until we asked the question, How will this affect the war in Vietnam?

We had gone to a tiny country that many Americans could not have found on a map. Yet, as opposition to the war grew, it was our own institutions that were threatened and our country that was in danger of being torn apart.

I went to Vietnam in the winter of 1965 as a 27-year-old reporter for my hometown Texas newspaper, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Until 1965, the American soldiers in Vietnam were advisers, but Lyndon Johnson had decided that spring to send in ground combat forces to fight the communists. By December, when I left for Saigon, thousands more were on the way.

Two years earlier, then Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had said the war was going so well he expected all American forces to be brought home by the end of 1965again ironically, the very period that Lyndon Johnson was beginning the buildup of American forces that would grow to 400,000 by the next year.

McNamaras rosy prediction of 1963 would be among the first of many government pronouncements that proved wrong.

My tour as a foreign correspondent did not get off to a great start. I arrived by commercial airliner at an airport in the Saigon suburbs, wearing a wool suit and lugging an 80-pound suitcase (this was before suitcases had wheels) only to discover that when it was winter in Fort Worth, it was stifling hot in Saigon and so humid that once off the plane I began sweating so profusely that I discovered sweat stains on the tops of my leather shoes.

I was the first Star-Telegram reporter to go overseas since World War II, so there was no one to meet me. I hailed a tiny cab, the driver tied my suitcase to the roof and I told him to take me to Saigon.

You in Saigon, he told me in broken English. Where you go in Saigon?

I had no idea. I had come to Vietnam to cover the war and realized I had no idea where it was.

By dark, I found the Associated Press bureau and Ed White, the bureau chief (and kindest man I ever knew), found me a place to stay, told me how to get credentials, and by the end of the week I was in the field, tracking down the Fort Worth kids I had come to write about.

As I look back on it, my arrival in Saigon very much paralleled Americas entry to Vietnam, a war that had been going on long before many Americans realized there was such a place.

I had gone there as a brash young hawk. I had come of age during the cold war with the Soviet Union, confident that a country that could win World War II could win any war. The government had been telling us that once and for all we had to draw a line and tell the communists they could not cross it. Better to draw that line in Vietnam than on our own shores. That seemed right to me.

Once there, I realized it was not so simple. So it was with Americas leaders. It took me a while to find the war; it took them longer to understand what it was about.

Six weeks later, on an operation with Marines and South Vietnamese forces near Da Nang, I realized that whatever our good intentions, this was not going to work. When the captain gave the order to move out, the Vietnamese troops refused to go. They made various excuses, then finally just set down.

It seems obvious in retrospect, but I understood for the first time that although we could help the Vietnamese, this was their war and we couldnt do it for them. What I was coming to understand was that these soldiers had been fighting long before we got there and they were tired of war, tired of the corruption that plagued their military. Maybe they were right to feel that way, but if thats how they felt, how could we help them? The farmers in the countryside were even less motivated: We thought we were fighting communists; all the farmers knew was that people had been coming through their villages for years with guns. They did whatever the people with guns told them to do. What I didnt understand was why the people in Washington didnt see what I was seeing. And before we fully understood what was happening, nearly 60,000 Americans would die.

As it always is in war, no matterwhat the historians later decide about its rightness or wrongness, the dead remain dead and the limbs once lost do not grow back.

This remarkable book tells in word and picture the tragic story of how we finally came to understand what going to Vietnam had wroughtboth there and here at homeand the tragic price we would pay.

We see in this book Vietnam before America got there, the war we fought and the chaos back home at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago when opposition to the war boiled over into a deadly riot. By chance I was there, and I remember wondering if the whole country was coming apart.

It did not, but I will always believe it came very close.

I found the final irony when I returned to Vietnam as a tourist in 1997. I found a thriving country that was emerging as a regional power where Americans were welcomed.

In part because of groundbreaking diplomacy by former Vietnam prisoners of war like Senator John McCain, who returned there to reconcile with the government that had tortured him, Vietnam was becoming Americas ally and wanted Americas friendship.

We had gained through forgiveness what we had been unable to change with our weapons.

When I had been in Vietnam during the war I found that many Vietnamese spoke French as a second language, and in 1997 I remember asking our guide if that was still the case.

Only my grandmother, he said. We all speak English now.

This book is the story of how that came to be.

Bob Schieffer is chief Washington correspondent for CBS News and moderator of Face the Nation.

Burrows, famous for finding ways to capture the impossible, would affix cameras to military aircraft and sometimes have the doors of planes removed so he could lean out and shoot as if he were outside the plane. Here, his photograph of AC-47 tracer fire pinpointing a jungle target in 1966. Photograph by Larry Burrows/LIFE

Next page