Preface

The first time I went to Japan, I went as a tourist. I went shopping in Ginza. I visited the ancient capital city of Kamakura. I gazed in awe at the giant Buddha and strolled meditatively through the serene peony garden where each delicate flower was ensconced in a miniature straw hut to protect it from inclement weather. I marveled at the sublime beauty of Japans haute cuisine and the bizarre excesses of its exorbitantly priced underworld. I even started keeping a diary of the unexpected items one can buy in vending machines, from ordinary household items like sake, beer, and kilo-sized bags of rice to truly specialized items like panties in a canunderwear allegedly preworn and autographed by high school girls. For better or worse, I was fascinated by it all. In fact, I was so dazzled by its unrelenting exoticism that I didnt think much about the real society that was going on underneathan odd omission considering the kind of work I do.

By trade I am a freelance labor activist. There is no established career path for my occupation. I get work by sticking my nose into the dark corners of society, where discrimination, injustice, and exploitation tend to lurk, until I find a situation where my skills might be of some help. I got in the habit when I was a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU). As part of a class assignment, I started nosing around the universitys labor management practices and found compelling evidence that the university had been engaging in a quiet campaign to bust the campus union and strip the universitys most vulnerable workersjanitors, food service and physical plant workersof decent wages, benefits, and a union contract. For more than a decade the university had been systematically whittling down the bargaining unit by hiring a subcontracted management company to take over operations in areas where the employees had unionized. In doing so, the administration could claim those unionized employees no longer worked for the university. Officially, they worked for the subcontractor and therefore their union contracts were null and void. (When I asked the universitys human resources director about the people who had been working at CMU for twenty years or more, she told me, Those people dont work for us. They work for [the facilities management company]. We have no relationship with them.) It was a favorite union-busting ploy of that era, and CMU, an institution named after two legendary philanthropists, or robber barons, take your pick, was more than eager to jump on that bandwagon.

Beyond the duplicity of CMUs campaign, the administrations actions were disturbing because they targeted the lowest paid workers on campus, many of whom were women and minorities; they took advantage of high unemployment in the area; and by cutting blue-collar jobs, wages, and employees access to benefits like tuition remission, they abandoned practices that had helped to strengthen communities and provide a ladder up for minority and low-income workers, adopting instead practices that increasingly resembled those of for-profit organizations.

Once I started looking in CMUs dark corners and saw what goes on there outside of the publics view and in stark contrast to the universitys carefully sculpted public image, I decided that bringing to light these kinds of employer practicesand, more importantly, working peoples responses to themwas what I wanted to do with my life. I started working on local labor issues in Pittsburgh in 1990 and, by the time I moved to Japan in 2000, I had worked on a wide variety of campaigns in the United States, including drives to organize home care providers, day care workers, and nursing home employees in Illinois, and public employees in Michigan. I had also written on labor issues related to steel workers in Indiana; UPS workers, janitors, truck drivers, prison employees, and college teachers in Chicago; and striking and locked-out factory workers in Decatur, IL. For ten years I was always on the lookout for burgeoning labor issues and signs of grassroots activism wherever they might be. And yet, during my first five days in Japan, the thought never even crossed my mind. Some combination of the sensory riot that is Tokyo and my own preconceived assumptions about the lack of labor activism in Japan left me temporarily blind to what was, in fact, a moment of great excitement and innovation in the Japanese labor movement.

Fortunately, I got a second chance. Two years later, upon hearing I was heading back to Tokyo, a friend with the United Electrical Workers (UE) asked me if I would be willing to work with the union to put pressure on the Japanese parent company of a US manufacturer that was stalling in contract negotiations with its newly organized workforce. I agreed, and, in the course of gathering background information I needed to do my part, I learned that the UE had long been actively cultivating organizational ties with some of the more progressive labor organizations in Japan, and that the two sides frequently engaged in activities to support each others campaigns. As Robin Alexander, the director of the UEs international division, brought me up to speed on the support the union was getting from left-leaning labor organizations in Japan, I realized two very important things: first, there was a lot more going on in the Japanese labor movement than was dreamed of in my philosophies (There are left-leaning labor unions in Japan?); and second, that I suddenly had an entre into a world that had been all but invisible to me until now.

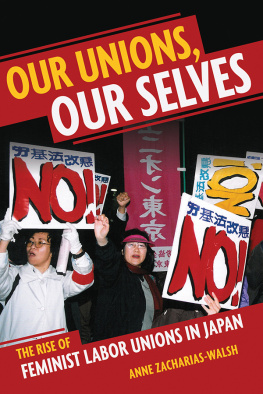

With Robins help, I was able to land interviews with some of the most influential progressive labor leaders, scholars, and grassroots organizers in Tokyo, all of whom told me that the Japanese labor movement was undergoing a period of intense reform as long-term marginalized workers had begun organizing new kinds of workers organizations outside and against traditional Japanese unions. For decades, the Japanese labor landscape was dominated by company-based enterprise unions, which often include only full-time regular employees of large, private firms. But beginning in the 1980s, progressives began organizing new, network-based community unions to represent the growing pool of workers who have traditionally (and purposefully) been left out of enterprise unions. Initially, efforts to organize community unions focused on part-time workers and employees of small- and medium-sized enterprises. But, as the economy started to crumble in the early 1990s and the government loosened regulations on short-term employment, more and more Japanese workers found themselves outside the regular workforce and therefore outside of enterprise unions sphere of influence. Suddenly, a much larger swath of the Japanese labor force was without union representation and they began looking to the community union model as an alternative. Within just a few years, a wide range of new community and individual membership unions had emerged throughout the country, including unions for part-time workers, nonregular workers, foreign workers, displaced workers, low-level managers, and, most surprising to me, unions for women only.

Until then, my work had never focused specifically on womens issues. I had always been interested in labor qua labor. But by the time I was conducting the interviews cited in this volume I had been in Japan long enough to see and be seriously disturbed by the relentless devaluing of women I saw at every turn. It was there in the sexist and sexualizing comments men blithely made about women in everyday conversations, in the way women at after-hours cocktail parties were expected to fix food plates and pour drinks for their male coworkers, and in the way a man blocking an aisle in a grocery store would refuse to move to the side to let a woman pass (let her be the one to walk around, damn it!). I had never experienced anything like it, even though it usually wasnt happening to me directly. As an obvious foreigner, I was somewhat outside the usual gender dynamic; Japanese men are well aware that Western women wont tolerate the kinds of Fred Flintstone-like behaviors they regularly rain down upon the heads of Japanese women. (I was frequently told I wouldnt have to worry about the notorious problem of men copping a feel on crowded subway trains because even the perverts know Western women fight back.) Still, just witnessing the pervasive subjugation was so suffocating and so infuriating that when I heard that some Japanese women were standing up and organizing their own renegade unions, I had to know more.