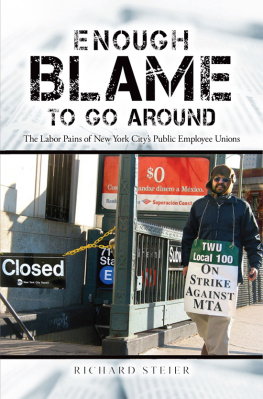

Praise for Enough Blame to Go Around

New York City's labor unions have been luckier than they deserved to have had reporter and editor Richard Steier around to spotlight their occasional triumphs and their much more frequent failures. Like Murray Kempton, another great New York columnist who loved the men and women of labor but who never suffered the fools who sometimes ran their unions, Steier's columns are filled with news, insight, and always compassion for those who ride (and drive) the early trains and buses to work.

Tom Robbins, CUNY Graduate School of Journalism

Steier presents an impassioned case for public sector unions and the benefits they have won, along with fascinating tales of the machinations inside several of the largest unions in New York CityDistrict Council 37, Transport Workers Union Local 100 and the 2005 strike that paralyzed the city, and the United Federation of Teachers.

Alair Townsend, former New York City Budget Director and Deputy Mayor

Enough Blame to Go Around

The Labor Pains of New York City's Public Employee Unions

RICHARD STEIER

Cover art by AP Photo/Shahrzad Elghanayan.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Cathleen Collins

Marketing by Anne M. Valentine

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Steier, Richard

Enough blame to go around : the labor pains of New York City's public employee unions / Richard Steier

pages cm. (Excelsior editions)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-4954-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Labor unionsNew York (State)History. 2. Labor unionsOfficials and employees. 3. Collective bargainingGovernment employeesNew York (State) I. Title.

HD6519.N5S74 2013

331.88'113517471dc23

2013005363

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my parents, who instilled in me an appreciation for the written word and offered a look at the fun side of the journalism business; and to Gilda, with love.

Acknowledgments

This book came about thanks to a suggestion by Rob Polner, who then provided a friend's guidance while helping me navigate my way to SUNY Press. My appreciation to Dan Janison, who when Rob floated the idea didn't dismiss it as silly.

My gratitude also to Jimmy Breslin, Robert Lipsyte, and Murray Kempton, whose work helped shape my sensibility; and to Tom Robbins, whose pieces for the Daily News and the Village Voice spurred more than one follow-up look at union funny business.

My informal education as a labor reporter was provided by officials from both sides of the bargaining table and a few neutral parties as well. They include Basil Paterson, Bruce McIver, Harry Karetzky, Bob Linn, Jim Hanley, Gary Dellaverson, Donna Lynne, Arvid Anderson, Marlene Gold, Steve DeCosta, George Nicolau, Jane Morgenstern, Estelle Karpf, Nat Leventhal, Stanley Brezenoff, Alair Townsend, Harvey Robins, Michael Jacobson, Bernie Rosen, Barry Feinstein, Bert Rose, Victor Gotbaum, Charles Ensley, Al Viani, Stu Leibowitz, Mark Rosenthal, Beverly Gross, Dennis Sullivan, Vinnie Montalbano, Norman Adler, John Toto, Jack Bigel, Jonathan Schwartz, Randi Weingarten, Jimmy Boyle, Nick Mancuso, Vinnie Bollon, Tom von Essen, Pete Gorman, Brenda Berkman, Sidney Schwartzbaum, Norman Seabrook, Arthur Cheliotes, Bill Henning, Larry Hanley, Eddie Kay, Jim Gebhardt, Tony Garvey, Bill Kelly, Floyd Holloway, Richard Wagner, Bob Croghan, Ray Diana, Phil Tacktill, and at least a dozen others who will be happy that I didn't mention them by name.

I owe thanks to my bosses at The Chief, Ed Prial and his brother Joe, who gave me the editorial independence needed to do the job right; and to other members of the Prial familyFrank II, Frank Jr., Jim, and Mike, who gave me the chance earlier to develop my skills and then write the column. Thanks also to Steve Jackel, a former colleague who is now the newspaper's lawyer, and to Harry Park, its head of production.

I am also grateful to those at SUNY PressMichael Rinella, Cathleen Collins, and Anne Valentinewho believed in the book and helped shepherd it into print.

Introduction

Over the past 40 years, the wages of ordinary workers in the United States, adjusting for inflation, have risen by just 1 percent, even as compensation for top executives has grown exponentially. There are several significant factors that account for that widening income gap, including computerization, globalization, and the tilt away from a level playing field that began with the presidency of Richard Nixon and was solidified by Ronald Reagan's transformation of the political dialogue in America.

But there is also an inescapable correlation to the decline of organized labor as a force in American life over that period. Four decades ago, roughly 35 percent of the nation's workers belonged to unions; today just about 12 percent do. In the process, as private-sector unions have declined in size and influence, the one area where labor has gained strength has been in the public sector, where collective-bargaining rights were not even granted until the late 1950s. In what seems particularly ironic today, the first state to enact those rights was Wisconsin in 1959, a year after they were adopted for New York City.

New York was a ripe area for labor ferment during the 1960s, beginning with a strike by welfare workers in the middle of the decade that was as much about the treatment of their clients as it was their own salaries and working conditions. The march to the barricades continued with a 1966 strike by transit workers that paralyzed the city for 12 days and a couple of years later by a sanitation strike and a months-long teachers strike that was fought not over wages but rather a bid by black militants to exert community control over public schools by, among other things, firing white instructors they claimed were inadequately educating minority pupils.

Eventually the spotlight dimmed as labor unrest quieted; New York's unions were credited with helping to rescue the city from the brink of bankruptcy in 1975, although critics claimed that too-generous contracts awarded to them by previous mayoral administrations were a major factor in the financial crisis. The bullet was dodged, and the unions in New York (where I live) gradually consolidated their gains, even as public worker unions in other parts of the country also prospered.

For much of the three decades after New York's fiscal crisis, public employee unions operated largely below the radar of the national and New York City media, unless a major scandal bubbled to the surface or, as with the city transit workers union in late 2005, a potentially crippling strike briefly focused attention on labor/management conflict before evaporating once the crisis passed.

The New York Times, which used to have a reporter assigned solely to covering municipal labor, discontinued the practice in the early 1980s, relying on its City Hall reporters or its national labor correspondent to step in once an alarm had sounded. The