MURDER

IN THE

GARMENT

DISTRICT

MURDER

IN THE

GARMENT

DISTRICT

THE GRIP OF ORGANIZED CRIME AND THE DECLINE OF LABOR IN THE UNITED STATES

DAVID WITWER AND CATHERINE RIOS

CONTENTS

MURDER

IN THE

GARMENT

DISTRICT

INTRODUCTION

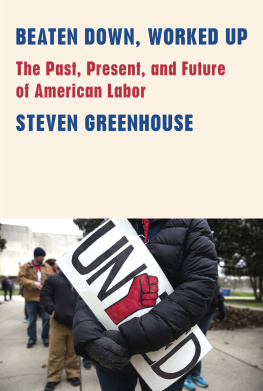

M ost Americans have little fi sthand knowledge about unions, and they know even less about the history of organized labor. Ironically, this is especially true for most working-class Americans. Often what they know about the subject comes through a mandatory orientation session when they get a job at one of the giant, non-union businesses that dominate todays economic landscape. At Walmart, the nations largest employer, all new hires watch a video that conveys the companys view of organized labor. The video features a handful of contented-looking actors portraying Walmart associates. And their message is fairly straightforward: We dont think that a labor union is necessary here. Other large corporate employers, such as Target and Delta Air Lines, follow a similar corporate strategy.

In conveying that message, these videos offer a succinct explanation of unions along with a brief summary of labor history. As one of the purported Walmart employees puts it, Funny thing is I always thought that unions were kind of like clubs, you know, or you know charities that were out to help workers. The video quickly moves to correct that impression. The truth is that unions are businesses, multi-million-dollar businesses, that make their money by convincing people like you and me to give them part of our paychecks. These videos also make it clear that this union enterprise is a failing business model. Both the Walmart and Target videos include a dramatic chart that illustrates the arc of twentieth-century labor history. A jagged line, descending from near the top of the charts left hand side, records organized labors former strength in this country, a time in the 1940s and 1950s when a third of the workforce belonged to unions. Back then, a Target employee explains, unions provided necessary protections, but now that role has become obsolete. Workers know that all the good things these unions once did are now law. Th s dubious historical claim goes unchallenged by the other Target employees in the film, who simply nod and smile in agreement.

In this version of labor history, union membership has fallen because workers dont want to pay costly union dues for protections they get for free from the government. To illustrate this point, an ominous downward chart line shows how membership rates have fallen dramatically over the course of the last couple of decades. Because union membership has dropped over the years to less than 8 percent of the private employers [workforce], Walmarts video explains, unions are fi hting to survive. The fewer members their business has, one Target employee observes, the less money they collect. And these orientations emphasize that it is the workers money that these unions are after, and their unscrupulous organizers are willing to do almost anything to get that money. In her book Nickel and Dimed, Barbara Ehrenreich describes sitting through one of these Walmart orientations: You have to wonderand I imagine some of my teenage fellow orientees may be doing sowhy such fie ds as these union organizers, such outright extortionists, are allowed to roam free in the land.

These corporate campaigns depict unions as fading, obsolete businesses; they also paint them as corrupt. In Walmarts training films unions are portrayed as essentially corrupt and parasitical institutions, according to the labor historian Nelson Lichtenstein.

A central message for these corporate campaigns is that their employees should be wary about turning over a share of their hard-earned paychecks to these unscrupulous, failing businessesaka unions. Instead of paying dues to a corrupt union, Delta urges its employees to consider the other great things they could buy with the $700 a year they might spend on dues. Workers might use that same money to buy a new video game system with the latest hits or buy a few rounds of beer for their buddies while watching a football game.

Critics have been quick to highlight the absurdities of Deltas argument. An article in the Los Angeles Times noted that while non-union Delta fli ht attendants averaged $58,341 a year in 2017, their unionized counterparts at United earned $62,461 and at American they made $62,366. Seen in this context, the $700 in dues money looks like a good investment. Indeed, statistics show that workers who pay union dues tend to reap signifi ant economic advantages from their membership in organized labor. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the median annual earnings for unionized workers is $52,700 versus $42,000 for non-union workers. Workers who belong to unions are more likely to receive employer-provided health insurance and pension benefits, and enjoy more vacations days. For women and minorities, the benefits of union membership are even more noticeable. A government study found that women union members earn on average 33 percent higher wages than non-union women workers; African American unionized workers take home 35 percent more in wages, and for Hispanic workers the increase is an impressive 51 percent.These union-gained advantages make it clear that organized labor still has an important role to play in protecting the well-being of American workers, despite the assertions made in corporate orientation videos.

But the corporate-sponsored version of labor history does get one central point right: unions have been on the decline. And their plummeting role has been particularly apparent in a manufacturing sector that had once been at the center of union strength. The story of one iconic American product offers a snapshot of this decline, and its impact on workers.

In 2012, thousands of workers who labored for Hostess Brands food corporation, the maker of the Twinkie, went on strike. In our current era of union weakness, such strikes have become relatively rare. That year there were just nineteen strikes nationwide that involved over 1,000 workers, and the total number of workers active in those strikes numbered about 148,000. Walkouts have become rare because unionized workers today are afraid to strike. Their unions are weak, and the employers hold almost all of the cards. By comparison, in the early 1950s, when, as Walmart has noted, organized labor accounted for nearly a third of the workforce and was reaching its zenith in power, workers felt secure enough to stage walkouts that extended the reach of their unions and won important gains in wages and workplace conditions. In 1952, for instance, there were 470 strikes in the United States that involved almost 2.8 million workers. Th oughout the 1950s, the number of strikes each year ranged between four hundred and five hundred, but in recent decades, as organized labor faded in strength, that number plummeted. By 2009, only five strikes involving 1,000 workers or more occurred that year across the entire country; in 2017, there were seven.

The walkout at Hostess, which involved Bakery Union members supported by Teamster truck drivers, quickly demonstrated the cause for labors timidity in this era. The private equity fi m that controlled Hostess chose to shut the entire corporation down rather than come to terms with their striking employees. A total of 8,500 workers lost their jobs. By 2013 another private equity fi m had snapped up key portions of Hostess, including the Twinkie brand, and rehired a fraction of the Hostess workforce as non-unionized employees. When

Next page