Table of Contents

Balance

Balance

How It Works

and What It Means

Paul Thagard

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2022 Paul Thagard

All rights reserved

EISBN 978-0-231-55607-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thagard, Paul, author.

Title: Balance : how it works and what it means / Paul Thagard.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2022] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021046717 | ISBN 9780231205580 (hardback) |

ISBN 9780231556071 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Equilibrium. | Motion.

Classification: LCC QC131 .T43 2022 | DDC 531dc23/eng/20211130

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021046717

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Philip Pascuzzo

To the heroes of the pandemic

Contents

T his book was written during the COVID-19 pandemic and is dedicated to the medical personnel, scientists, engineers, and leaders who have kept it from being an even larger disaster.

For helpful suggestions, I am grateful to Chris Eliasmith, Laurette Larocque, Adam Thagard, and Dan Thagard. For valuable comments on an earlier draft, I thank Kate Anderson, Steve Bank, Jim Bauer, Rob DeSalle, Randy Harris, John Holmes, Lauren Talalay, and Joanne Wood. Anonymous reviewers provided some annoying comments that prompted improvements.

I have recycled some material from my Psychology Today blog, Hot Thought, for which I hold copyright.

Thanks to Miranda Martin, Kathryn Jorge, and Ben Kolstad for editorial support, Susan Zorn for copyediting, and ARC for the index.

Supplemental material including live web links can be found at paulthagard.com.

I took balance for granted until 2016, when I had a nasty bout of vertigo. I was getting up from the weight bench in my basement when the room started to spin wildly. I almost fell off the bench and could only walk upstairs by holding on to the railing and wall. The next day I could get around with a cane and saw my family doctor, who had me lie down and turn my head to the side. Dr. Wang noticed that my eyes were moving in an odd pattern called nystagmus, and she diagnosed me as having benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. This kind of vertigo is caused by errant calcium crystals in the inner ear and counts as benign because the crystals can be moved back in place by a head-positioning exercise called the Epley maneuver. Now, if I start to feel even a bit dizzy, I do the maneuver and vertigo is prevented.

My family members and friends have had other forms of vertigo. My son Adam was laid out for a week by extreme vertigo from a cold that developed into an ear infection. My other son Dan felt wobbly as one of the symptoms of a scary case of COVID-19. Many years ago, a friend of mine suffered from Mnires disease, an ear disorder that causes extreme vertigo and nausea. Another friend has severe vertigo resulting from ministrokes that caused damage in his midbrain and cerebellum. Dizziness is among the most common problems that patients report to their doctors, and falling puts older people at major risk of fractures. What goes wrong in our balance systems to produce vertigo, dizziness, and falling?

In 2019 I saw that my local recreation center was offering courses in tai chi, an ancient Chinese form of exercise said to improve balance. I had seen tai chi in movies and thought it looked incredibly slow and boring. But I learned from the course that performing intricate routines at a controlled pace is challenging both physically and mentally. I was heartened by evidence that tai chi dramatically reduces falls in older people and has numerous other well-documented health benefits. I wrote a blog post that explained the effectiveness of tai chi in terms of cognitive neuroscience rather than the traditional Chinese medicine concepts of yin, yang, and qi.

Thinking about balance, vertigo, and tai chi made me notice that varieties of balance are important in many domains. Biologists talk about the balance of nature and chemists determine if a reaction is in equilibrium. Economists debate whether budgets should be balanced and politicians worry about the balance of powers. The traditional visual symbol for the law is the balance scale, which is also the image for my astrological sign of Libra. People fret over whether they are eating a balanced diet and managing an appropriate work-life balance. Unbalanced minds suffer from maladies such as depression and anxiety. One of my favorite movies is Alfred Hitchcocks Vertigo. Reflective equilibrium is an influential concept in philosophy.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 20202022, debates raged about how much public life and the economy needed to be locked down to prevent the spread of the disease. These debates concerned how to balance lives against livelihoods and health against . Health officials recommended strong measures such as closing businesses, but many political leaders tried to keep the economy functioning. Other conflicts in this balancing act included reconciling individual freedom with social controls such as requiring people to wear masks and to practice social distancing.

Figure 1.1 Balancing lives and livelihoods in the COVID-19 pandemic, showing Premier Doug Ford of Ontario, Canada.

Source: Graeme MacKay/Artizans.com. Reprinted by permission.

I became increasingly curious about how the concepts of balance and vertigo are used in diverse fields and how these uses are related to biological ideas from physiology and medicine. Is there any connection between balancing the body and balancing the world, between physiology and society? This book begins with biological explanations of how the brain manages to balance the body and of how breakdowns in this management can lead to failures such as vertigo. A crucial question neglected by balance experts is why conscious feelings are associated with successful balance and especially with breakdowns such as dizziness and vertigo.

Literal kinds of balance, as well as failings such as vertigo, give rise to rich metaphors that pervade discussions of nature, medicine, society, the arts, and philosophy. I will show that the brains ability to interpret many kinds of sensory inputs that influence balance is mirrored by the coherence and usefulness of many balance metaphors. Our minds expand on the bodys balance to understand the rest of the world.

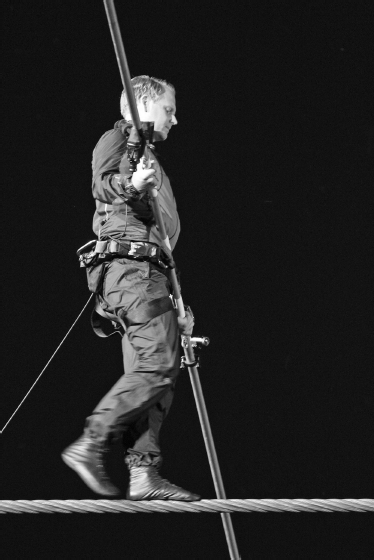

In 2012, Nik Wallenda walked a tightrope across Niagara Falls (). He had to deal with high winds, wet air, and a narrow rope, whereas ordinary people only have to walk along sidewalks and paths. But even ordinary walking has its perils, such as sidewalk cracks to step into and pathway roots to trip over. Nevertheless, people usually manage to make their way around the world without falling down or getting dizzy.