Published by

Vij Books India Pvt Ltd

(Publishers, Distributors & Importers)

2/19, Ansari Road,

Delhi - 110002

Phones: 91-11-43596460, 91-11-47340674

Fax: 91-11-47340674

e-mail:

Parts of this book were previously published as Trading Legitimacy by ENC Press 2008

2012 - 2013 by the Burma Centre for Ethnic Studies

Burma Centre for Ethnic Studies

Email:

Website: www.burmaethnicstudies.net

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Application for such permission should be addressed to the publisher.

The views expressed in the book are of author/editor and not necessarily those of the publishers.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Lian Sakhong, Professor Nordquist, Sai Mawn, Sai Khunsai Jaiyen, Khu Oo Reh, Ta Doh Moo, Khaing Soe Naing Aung, Saw Htoo Htoo Lay, Nai Han Tha, Dr Khin Maung. Khun Okker, Dr Tu Ja, Mai Aik Phone, and Edmund Clipson for their invaluable assistance in preparing this book.

Foreword

In light of recent and constructive changes in the country, more and more people have become interested in Burma or Myanmar as it was officially renamed in 1989. However, already the name of the country illustrates one of many contentious dimensions in its modern history, something that makes the name still a controversial issue, inside the country and especially outside.

There are a number of such conflict-prone dimensions on the agenda of the modern history of Burma. It is not without reason that the country was made a federation at its independence in 1948. With its many ethnic minorities, and with religious and linguistic diversity criss-crossing regional boundaries, one doesn't need to spend much time before realizing that in order to grasp the background to today's situation, one needs a guide with deep local knowledge.

Paul Keenan is this excellent guide in the historic and modern landscape of ethnic minorities and movements in Burma. This study focuses on those that gradually found it necessary to defend their cause by force of arms in the wake of an unfulfilled constitution for the Union of Burma as the country was then called in 1948. As the reader will be aware, what happened at that time still shapes important dimensions in today's situation.

In this book, Mr Keenan gives the reader both a structure and a lot of detailed information about how the modern history of these movements has unfolded until today. This double quality makes the book both a reader and a reference text, invaluable for anyone interested in getting behind the headlines and into a political reality that affects millions of people in Burma today.

Professor Kjell-Ake Nordquist

Board Chairman

Burma Centre for Ethnic Studies

Former Dean, Faculty of Peace and Conflict Studies

Uppsala University, Sweden

Introduction

The Dynamics of Sixty Years of Ethnic Armed Conflicts in Burma

Lian H. Sakhong

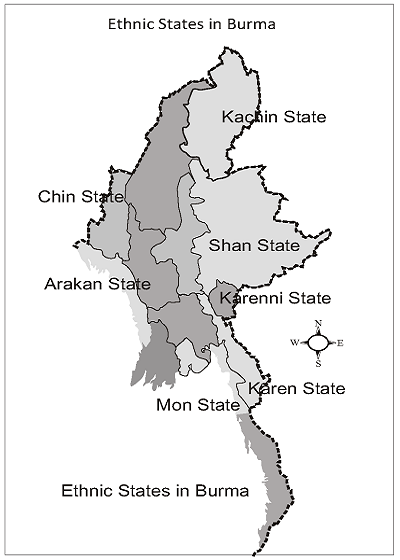

The Union of Burma is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in Asia, which continues to suffer one of the longest internal ethnic armed conflicts in modern times. As a post-colonial modern nation-state, the Union of Burma was founded by pre-colonial independent peoples, namely the Chin, Kachin, Shan, and other peoples from what was termed Burma Proper, who in principle had the rights to regain their national independence from Great Britain separately and found their own respective nation-states. Instead, they all opted to form a Union together by signing the Panglong Agreement on 12 February 1947, based on the principles of voluntary association, political equality, and the right of self-government in their respective homelands through the right to internal self-determination, which they hoped to implement through a decentralized federal structure of the Union of Burma. In order to safeguard the above principles, the 'right of secession' from the Union after ten years of independence was guaranteed to every states, that is., all ethnic nationalities who formed member states of the Union, as it was enshrined in Chapter X, Articles 201-206 of the 1947 Constitution of the Union of Burma, and adopted as one of the founding principles of the Union.

Burma, however, did not become a federal union as it was envisaged in 1947 at the Panglong Conference. Instead, it became a quasi-federal union with a strong connotation of a unitary state where a single ethnic group called the Burman/Myanmar people controlled all state powers and governing systems of a multi-ethnic plural society of the Union of Burma. Consequently, the root cause of ethnic inequality and political grievances was borne out of this constitutional problem. Another major problem that confronted Burma from the very beginning was what social scientists called 'state formation conflict' which brought the country into civil war soon after independence. The 'state formation conflict' broke up because the 'make-up' of the Union was not inclusive.

Since the Panglong Agreement was signed by peoples from pre-colonial independent nations, that is., the peoples who were conquered independently by the colonial power of Great Britain, not as part of the Burman or Myanmar Kingdom; three major ethnic nationalities from Burma Proper, namely, the Arakan, Karen, and Mon peoples were not invited officially to the Panglong Conference. They were represented by General Aung San as peoples from 'Burma Proper', that is., a pre-colonial Burman or Myanmar Kingdom. The futures of these peoples, especially the Karen who had already demanded a separate state, were not properly discussed at the Panglong Conference, which eventually triggered the first shot of ethnic armed conflicts in the form of a 'state formation conflict' in 1949. Unfortunately, ethnic issues in Burma remain unsolved and as a result over sixty years of civil war continues today.

In addition to this state formation conflict, which is a conflict between the government and the identity-based, territorially focused, opposition of ethnic nationalities; another dimension of internal conflict in Burma, that arose out of independence, was the misconception of 'nation-building' for 'state-building', or what became the confusion between 'nation' and 'state', which resulted in the implementation of the 'nation-building' process as a process of ethnic 'forced-assimilation' by successive governments of the Union of Burma. The 'nation-building' process with the notion of 'one ethnicity, one language, one religion' indeed reflected the core values of Burman/Myanmar 'nationalism', which originated in the anti-colonialists' motto of 'Amyo, Batha, Thatana, that is to say, the Myanmar-lumyo or Myanmar ethnicity, Myanmar-batha-ska or Myanmar language, and Myanmar-thatana of Buddha-bata or Buddhism, and it has become after independence the unwritten policies of 'Myanmarization' and 'Buddhistization', and a perceived legitimate practices of ethnic and religious 'forced-assimilation' into 'Buddha-bata Mynamar-lumyo' (that is, to say 'to be a Myanmar is to be a Buddhist'), in a multi-ethnic, multireligious plural society of the Union of Burma.

In the process of implementing the 'nation-building' with the notion of 'one religion, one language, one ethnicity', the successive governments of the Union of Burma, dominated and controlled by ethnic Myanmar, have been trying to build an ethnically homogenous unitary state of