Contents

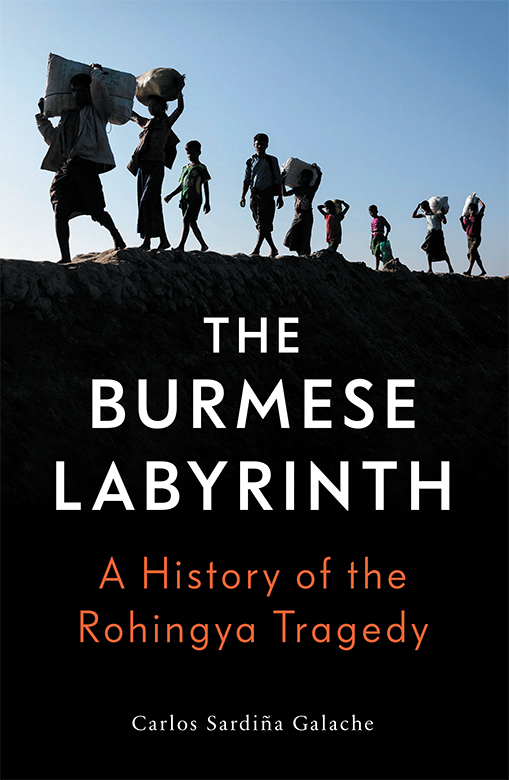

The Burmese Labyrinth

The Burmese Labyrinth

A History of the Rohingya Tragedy

Carlos Sardia Galache

First published by Verso 2020

Carlos Sardia Galache 2020

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

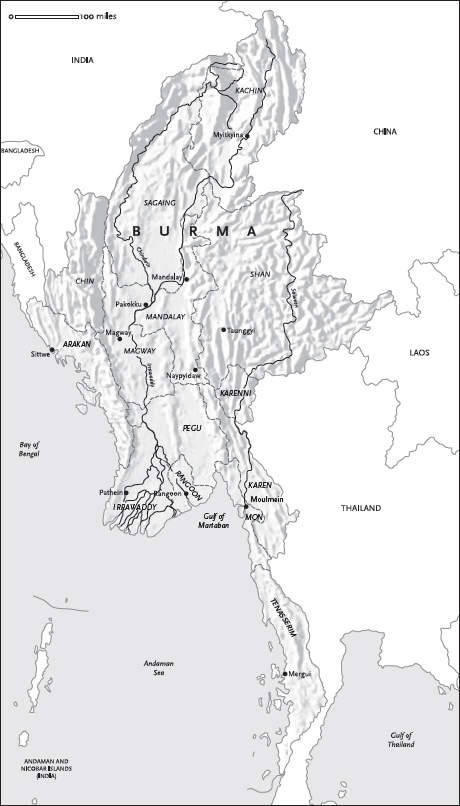

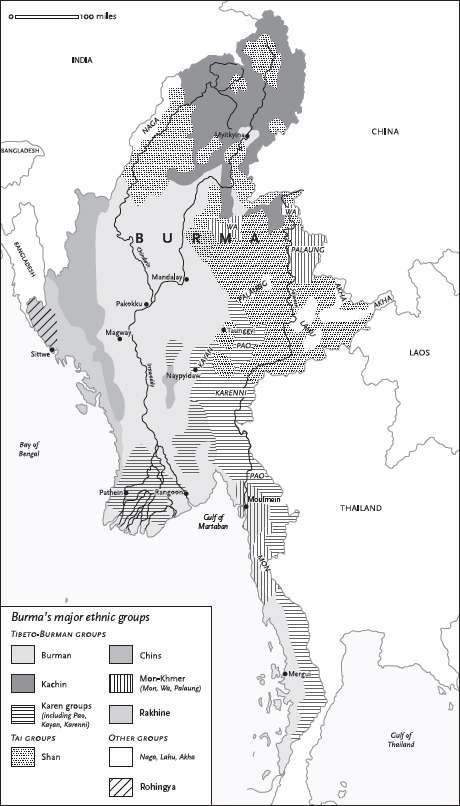

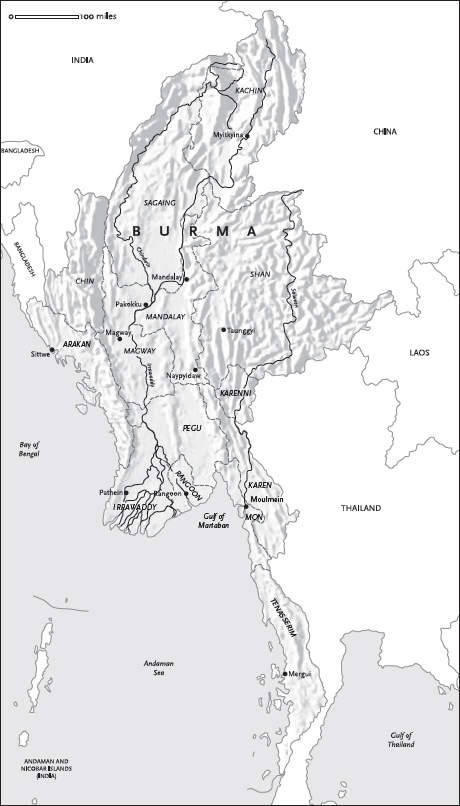

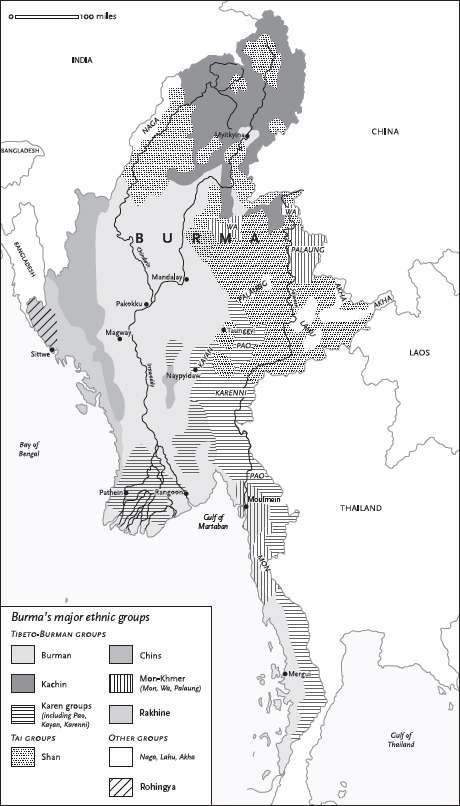

The maps on pages vi and vii are reproduced with permission from New Left Review, where they first appeared in Mary Callahans Myanmars Perpetual Junta.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-321-2

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-320-5 (LIBRARY)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-322-9 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-323-6 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Minion Pro by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

Part I

Discipline-Flourishing Democracy

Part II

History and Its Traces

Part III

A Diarchic Government

In 1989, the military junta ruling Burma changed the official name of the country, and those of several regions and cities, returning them to their old names in the literary Burmese language. By the Adaptation of Expressions Law, both Burma and Burmese were changed to Myanmar. The change only affected languages other than Burmese, as Myanmar had been the official name of the country in the language of the Burman majority. One of the explanations was that Burma had been imposed by the British colonial power. But that was not entirely true, since Burma is just a transliteration of the less formal word for the country in Burmese, and not a new name imposed by the colonial overlord as is the case, for example, of the Philippines, a completely new name coined by the Spaniards in honour of the conquering King Philip II. In reality, Burma and Myanmar mean exactly the same, and asking speakers of other languages to use one instead of the other is the equivalent of asking non-German-speakers to use Deutschland instead of Germany.

The United Nations and some governments accepted the change, but many other countries and the international media continued to call the country Burma. There was a time when choosing one term or the other had political connotations, as Aung San Suu Kyi had opposed the change. But Myanmar has become internationally accepted since the transition in 2012. Throughout this book, I will use the name Burma, except when quoting other writers or public documents where Myanmar is used. This is both a matter of personal preference and a function of the fact that, for most of the long period covered in the book, the country was known as Burma.

The name of the state of Arakan was changed to Rakhine in 1983, probably to please Rakhine nationalists. Throughout this book, I use Arakan to refer to the state, and Rakhine to refer to the majority ethnic group in Arakan, as I understand Arakan, the place, to have more inclusive connotations.

The majority group in the country is called Bamar or Burman. I have opted for Burman because it is consistent with the use of Burma rather than Myanmar. Burmese refers to any citizen of the country, regardless of ethnicity. But the Burmese language is that spoken by the Burman majority. In colonial times, it was the other way round: Burmese was used for the ethnic group Burman. I have noted this when necessary. It is also worth pointing out that many members of the ethnic minorities use Burmese when referring to the Burmans. This shows the extent of confusion about national identity and the failure to create a multi-ethnic Burmese nationalism.

In some press reports and books that adopt the Myanmar terminology, some names are different to those used in this book. I show here the equivalent variants of the most important names for states and cities used throughout the book (others, such Kachin, are the same in both terminologies):

| Burma (country)/Burmese (citizens of, language) | Myanmar |

| Burman (ethnic group) | Bamar |

| Rangoon (city) | Yangon |

| Arakan (state)/Arakanese (ethnic group) | Rakhine |

| Irrawaddy (river and division) | Ayeyarwady |

| Karen (both state and ethnic group) | Kayin |

| Karenni (both state and ethnic group) | Kayah |

| Moulmein (city) | Mawlamyine |

| Tenasserim (division) | Tanintharyi |

Members of ethnic groups like the Burman, Mon or Rakhine, do not have surnames, so their names are repeated in full every time they are mentioned with the exception of Aung San Suu Kyi, who is often called simply Suu Kyi. Other ethnic groups like the Kachin or Chin names do often include family or clan names, and sometimes individuals may be referred to only by their surnames.

The Burmese often use honorifics determined by the relative age or social status of the person addressing them. For instance, to refer to a mature woman, or one holding a senior position, the speaker would add Daw (as in Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, used often in Burmese media). For senior men, either by age or position, U is commonly added (as in U Nu). Further examples of these honorifics include the following:

| Daw | for mature women and/or women occupying senior positions (roughly equivalent to aunt or Ms) |

| Ma | for young women or women of roughly the same age as the speaker (roughly equivalent to sister or Ms) |

| U | for mature men and/or men occupying senior positions (roughly equivalent to uncle or Mr) |

| Ko | for young men or men of roughly similar age to the speaker (roughly equivalent to brother) |

| Maung | for younger men, often part of the name |

| Saya | for teachers or older men with special status |

| Ashin | for monks |

| Sayadaw | for senior monks |

| Bo | for military commanders |

| Bogyoke | for military generals |

| Thakin | master, used by the nationalists in the 1930s and 1940s to indicate that they were the masters of their own country |

I have not used these honorifics except in cases when they are so closely associated with the name of the person that they are rarely omitted (as in the case of the first prime minister of independent Burma, U Nu), or when quoting others using them.

Introduction: Trapped in

the Burmese Labyrinth

How can we understand the violence and turmoil in Burma during most of the last decade, particularly the brutal ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya, a Muslim minority living in the west of the country? This has been a period of profound political and social changes in the country. Since 2011, the military junta that had ruled for decades has dissolved itself, the army loosened its tight grip on power, and initiated a carefully managed transition to a pseudo-democratic system. As a consequence, while maintaining considerable control over the state apparatus, the military allowed a degree of opening that resulted in new freedoms that the Burmese had not enjoyed for decades.